The ability of cancer cells to spread from one part of the body to another - a process known as metastasis - is one of the reasons why cancer can be extremely challenging to treat.

But in a recent study, researchers from CDE have pulled back the curtains on the complex interactions between tumour cells and the microenvironment, showing that some cancer cells are resilient to mechanical stress and such cells also have a stronger ability to multiply rapidly to form secondary tumours.

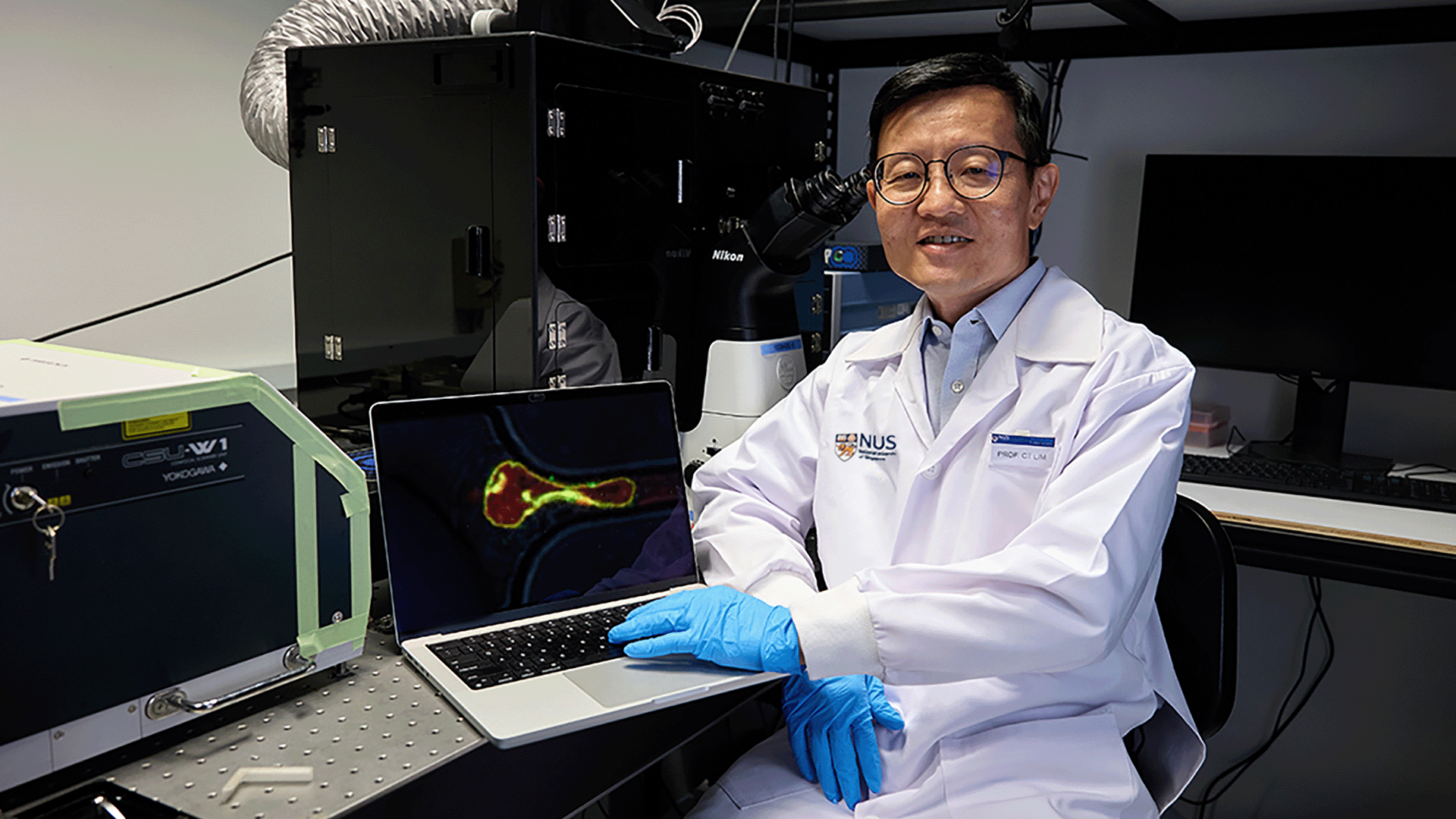

“Understanding how some cancer cells can survive mechanically-induced cell death is key to preventing the spread of malignant tumours, and paves the way for more targeted therapies,” said lead author of the research Professor Lim Chwee Teck from the Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Prof Lim, who is also Director of the NUS Institute for Health Innovation and Technology, and his team reported their findings, a culmination of four years of research work, in the scientific journal Advanced Science.

Immune surveillance

The human body possesses a defence mechanism – known as immune surveillance – that targets circulating cancer cells in the bloodstream. This mechanism plays a crucial role in detecting and eliminating cancer cells.

The physical microenvironment in the form of tiny blood vessels, called capillaries, with diameters much smaller than that of circulating cancer cells, also plays a role in ‘filtering’ out these cancer cells. Such narrow capillaries create physical barriers that restrict the passage of larger cancer cells. Cancer cells that cannot deform or squeeze through these tight spaces may become trapped or damaged, preventing their further dissemination.

To investigate how certain circulating cancer cells avoid being ruptured by these forces, the research team designed a new experimental method to ‘force’ different cancer cell lines through a series of small, capillary-sized constrictions.

In the process, the majority of the cancer cells were ruptured and killed. But the researchers also observed that a small population of each cancer cell line emerged relatively unscathed.

They further analysed these surviving cancer cells and discovered that they carried a distinct molecular signature compared with the original set of cancer cells. Intriguingly, the researchers discovered that the ability of these cells to survive and proliferate was linked to specific properties of their nuclear membrane proteins, nuclear stiffness, and their self-repair capabilities.

They characterised the surviving cancer cells as ‘mechanoresilient’, finding that in these cells, the DNA damage repair machinery, which is critical for cellular survival, was enhanced and more active than usual.

Moreover, these cells also exhibited greater malignancy – they could multiply more rapidly compared to the original cells and were also less susceptible to chemotherapy drugs.

Through a meta-analysis of different cancer types using data from cancer genome database, the researchers showed that the altered gene expression profiles in these cancer cells were linked to poorer disease prognosis and patient outcomes.

Mechanical stress

The team also uncovered an unexpected link between the cancer cells’ exposure to mechanical stress, and the onset of metastatic development.

Although previous studies have shown that metastasising cancer cells are more invasive and resistant to cancer therapies compared to localised cancer cells in primary tumours, it was not previously clear if mechanical stress played a direct role in this transformation.

In their study, researchers put the cancer cells through multiple rounds of mechanical stress and concluded, for the first time, that mechanical stress could potentially contribute to the surviving cancer cells gaining proliferation ability and drug resistance.

Understanding the molecular traits of mechanoresilient cancer cells thus opens up a new avenue for cancer treatment. Therapeutic approaches could potentially be developed to target specific nuclear membrane proteins and inhibiting the self-repair ability of the cancer cells to achieve positive treatment outcomes.

Additionally, identifying the biomarkers associated with mechanoresilience in cancer cells can be used to diagnose or even predict patient response to therapy.

Further research may also contribute towards the development of a novel diagnostic method for cancer.

For example, a detailed imaging of the cancer cell nucleus could reveal the presence of mechanoresilient cells, to help doctors in selecting a suitable treatment option that prevents the onset of metastasis.