Plastic is not just a convenience of everyday life. It has quietly become one of our greatest environmental challenges.

Among its insidious forms, microplastics (tiny plastic fragments less than 5 mm in size) are emerging as a pervasive pollutant, found not only in our rivers, oceans and soils but in the water we drink, the air we breathe and the food we eat. Their small size allows microplastics - and even smaller and potentially even more toxic nanoplastics - to circulate through ecological systems, entering food chains, and potentially impacting human health in ways that are only just becoming apparent.

Against this background, the Symposium on Microplastics in the Environment and Water: Challenges, Research, and Mitigation Strategies brought together scientists, policy-makers, and other stakeholders across the region to share research, debate standards and strategies, and explore collaborations to confront the growing impact of microplastic pollution.

In the keynote session Professor Hyunook Kim from the University of Seoul underscored just how pervasive this issue has become. His research revealed how tiny plastic particles can slip into our waterways from daily household laundry cycles.

Prof Kim’s team tested popular detergents and softeners and found thousands of microplastics hidden in just a millilitre of product. He emphasised that unless ways are found to improve the way we monitor and regulate these products, this everyday household chore will continue to feed a global pollution problem.

A second keynote from Professor Atsuhiko Isobe of Kyushu University introduced the Atlas of Ocean Microplastics (AOMI), a comprehensive global database to track and analyse microplastic contamination at sea, offering a powerful tool for both researchers and policymakers.

On day two of the symposium, a third keynote by Professor Rong Ji from Nanjing University highlighted how plastics break down once they enter the environment. Using a radiocarbon tracing technique, his team showed that ageing processes such as sunlight and oxidation can make microplastics more vulnerable to microbes, speeding up their mineralisation. The findings underline that weathered plastics are not inert, but continue to change, an insight that Prof Rong said could be a powerful tool in improving how we track and control the long-term impact of microplastics.

Hidden risks

Across the two days, the programme featured contributions from researchers from Malaysia, the Philippines, India, Japan, Korea, China, Italy and beyond, providing perspectives shaped by their own environmental contexts.

From CDE, four researchers presented work that highlighted both the hidden risks of microplastic exposure and possible strategies for mitigation.

Dr Xiaorui Wu of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and a research fellow at the NUS Environmental Research Institute (NERI) under Associate Professor Liya Yu focused on airborne microplastics, a relatively new area of concern. By studying the atmosphere during the COVID-19 pandemic, when travel and industrial activity were disrupted, her team was able to distinguish between local and long-range sources of plastic particles in the air. This work adds to growing evidence that microplastics are not just a waterborne problem, but one that also affects the air we breathe.

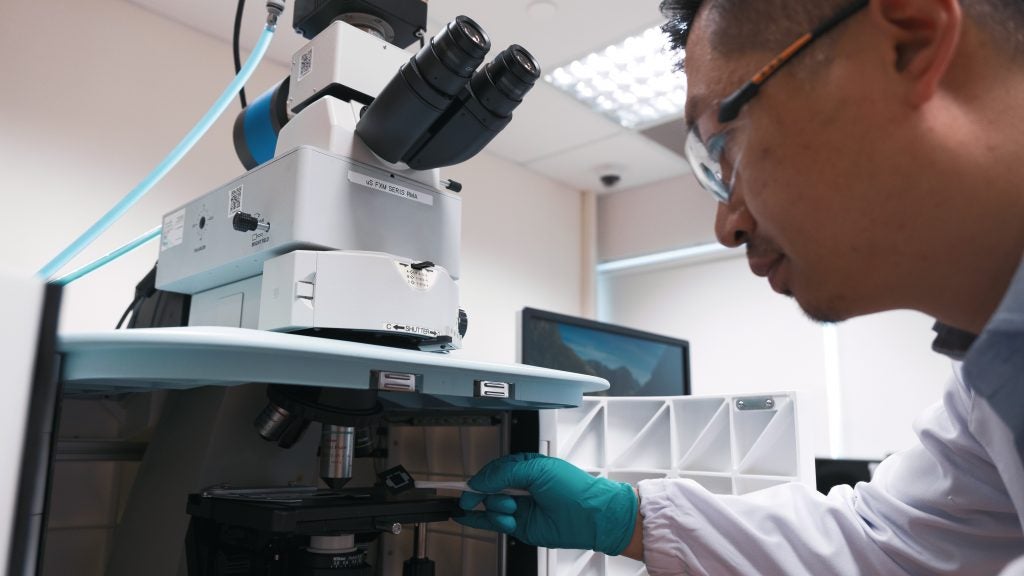

PhD student Xin Le from the Department of Biomedical Engineering used hyperspectral stimulated Raman scattering (SRS), a cutting-edge, non-destructive imaging technique, to trace how micro- and nanoplastics move through living zebrafish.

Zebrafish are increasingly used in toxicology studies because of their genetic similarity to humans, rapid development, and transparent embryos, which make them ideal for tracking changes in real time. Xin showed that plastic particles can accumulate in vital organs such as the fish’s liver, gut and even the brain, where they disrupt lipid metabolism and trigger inflammation. He also highlighted how zebrafish sometimes mistake microplastics for food, leading to a starvation-like effect as the plastics provide no nutrition. “The smaller particles could cross into the brain and blood vessels, suggesting more severe cardiovascular and neurotoxicity,” he said, which raised important questions and concerns for human health.

Plastic road

On day two of the symposium, Dr Meibo He, research fellow at NERI under Professor Raymond Ong (Civil and Environmental Engineering) presented results from Singapore’s first trial of a “plastic road”, where recycled low-density polyethylene (LDPE) waste was incorporated into asphalt.

While producing the plastic-modified asphalt carried a slightly higher environmental burden upfront, monitoring showed it could last longer than conventional asphalt, reducing maintenance and carbon emissions over its full life cycle. Importantly, Dr He also tested the impact on water quality, since roads in Singapore double as part of the nation’s water catchment system. Early findings were reassuring, with no significant differences observed in key water parameters, she said.

PhD student Thitiwut Maliwan of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering under Professor Jiangyong Hu examined household ultrafiltration membranes, widely marketed as the “last line of defence” in drinking water systems. Over a year of monitoring, he found that while these membranes can trap microplastics effectively (sometimes even improving in performance as biofilms formed), they also have the potential to release plastic fragments of their own, since the membranes are themselves made of polymers.

Using machine learning, he analysed the interplay of water quality, membrane condition and microplastic release. “We found that fouling, usually seen as a problem, can actually help capture microplastics more effectively, but the membranes themselves can still contribute plastics into the water,” he noted.

The symposium closed on a forward-looking note, recognising both the progress made and the scale of work still ahead.

“The research presentations we heard showed us how much progress has been made, but also how much more remains to be understood about microplastics, especially the smallest nanoplastics that we still struggle to detect,” said Professor Hu Jiangyong (Civil and Environmental Engineering), who led the organisation of the symposium as co-chair. “The diverse contributions from speakers across different countries gave us a fuller picture of the problem and the solutions being developed, from case studies and technical advances to policy frameworks.”

Reflecting on her takeaways from the symposium, Prof Hu said: “What excites me most is the potential for new collaborations that were sparked here, as we share methods, data and innovations across borders. At NUS and CDE, we are committed to continuing this work, from studying the impacts of microplastics on ecosystems and health to developing solutions in monitoring, removal, recycling and upcycling, and contributing to both local and global control of microplastic pollution.”

The Symposium on Microplastics in the Environment and Water was held from 18–19 September 2025 and jointly organised by the NUS Environmental Research Institute (NERI), the Centre for Water Research (CWR) at the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at CDE, and the SG Lab Forum as part of NUS Sustainability Connect 2025.