A dissolving microneedle patch that delivers biofertilisers straight into plant tissue has been shown to speed vegetable growth while cutting fertiliser use by more than 15 per cent compared to traditional methods.

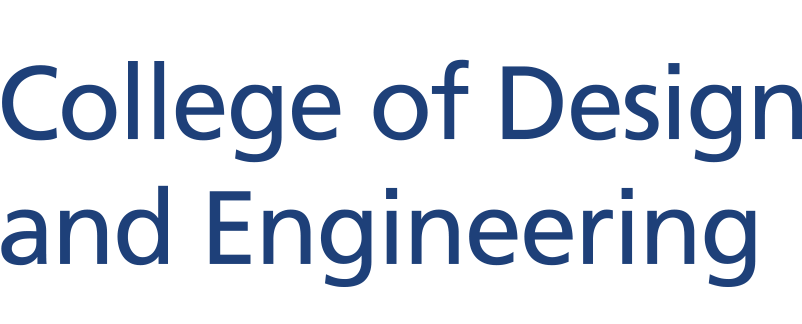

Developed by a research team led by Assistant Professor Andy Tay (Biomedical Engineering and Institute for Health Innovation & Technology (iHealthtech)), the system bypasses soil barriers to place beneficial microbes where they are most effective.

The approach points to more precise fertiliser delivery, less waste and potentially lower environmental impact, with near-term fit for urban and vertical farms and for high-value crops that benefit from controlled dosing.

Biofertilisers, which contain beneficial bacteria and fungi that help crops absorb nutrients and tolerate stress, are usually added to soil. There, they must compete with native microbes and can be hindered by acidity and various other conditions, meaning much of the input never reaches the roots.

By placing beneficial bacteria or fungi directly into leaves or stems, the new method bypasses those hurdles and accelerates early gains.

The study was published in Advanced Functional Materials on 13 September 2025.

“Inspired by how microbes can migrate within the human body, we hypothesised that by delivering beneficial microbes directly into the plant’s tissues, like a leaf or stem, they could travel to the roots and still perform their function, but much more effectively and be less vulnerable to soil conditions,” Asst Prof Tay said.

How the patches work

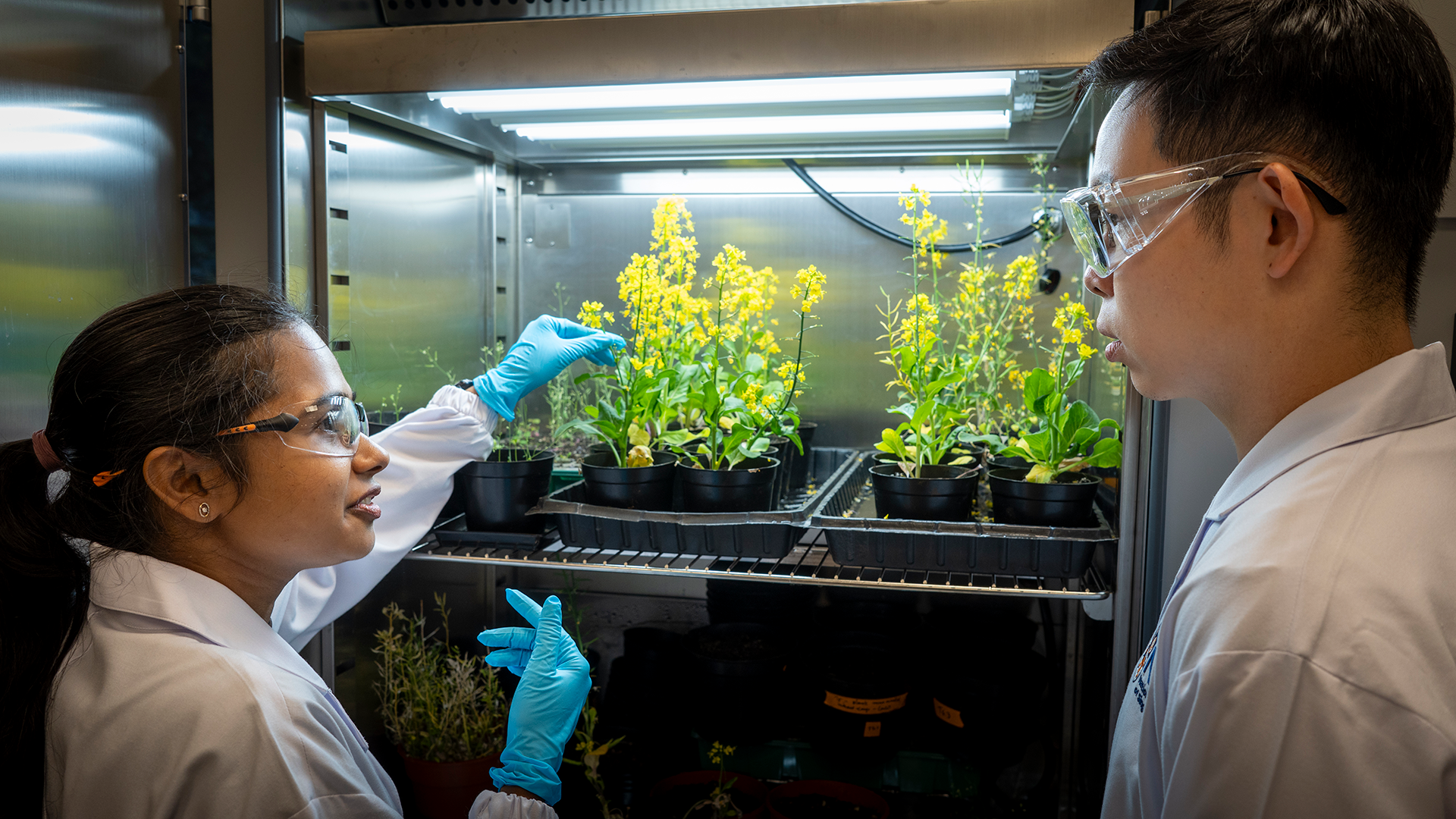

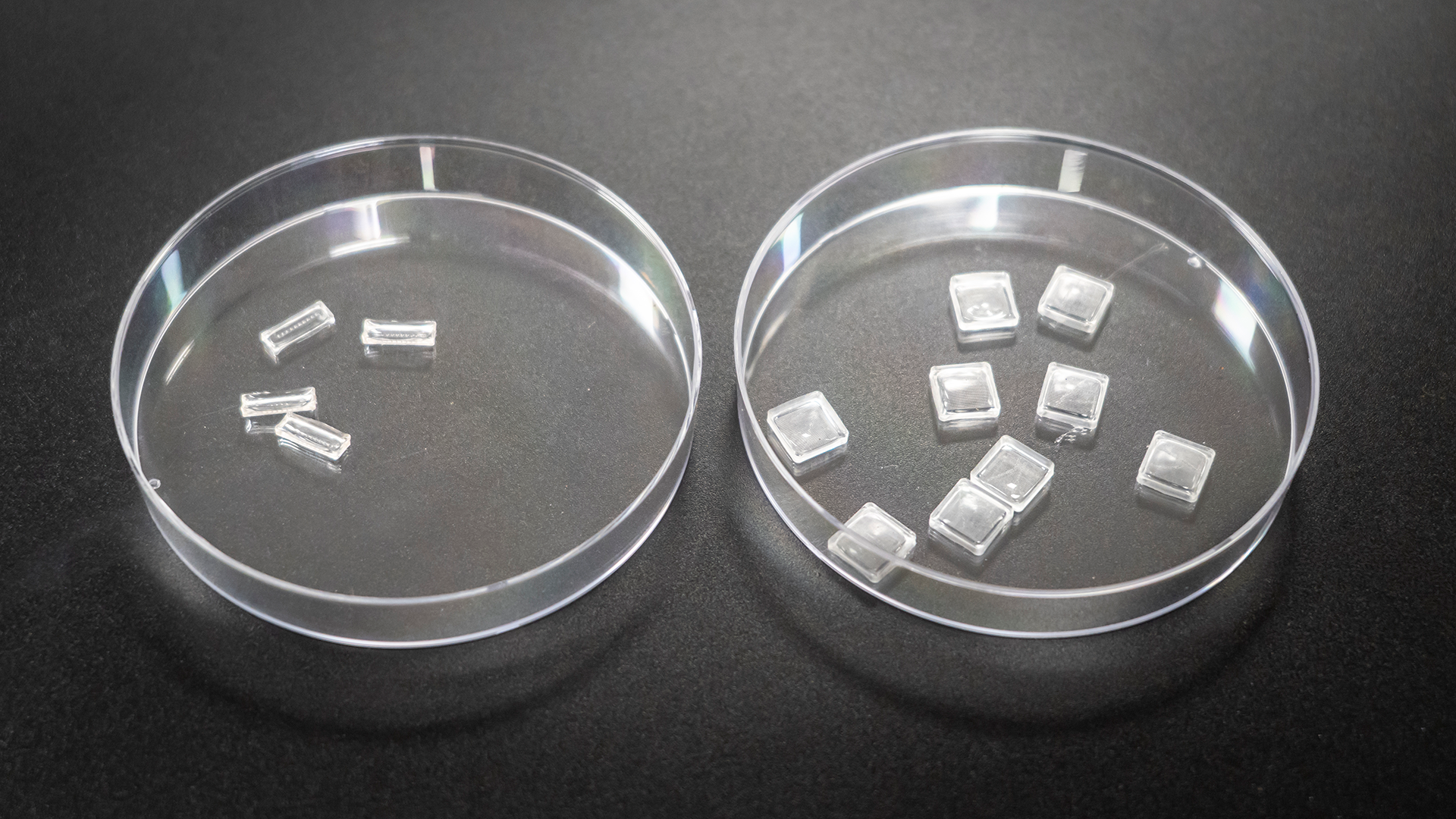

The researchers fabricated plant-tuned microneedles from polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a biodegradable, low-cost polymer. For leaves, a 1 cm by 1 cm patch carries a 40 by 40 array of pyramids about 140 μm long, while a short row of roughly 430-μm needles suits thicker stems. Microbes are blended into the PVA solution, cast into tiny moulds and locked in the needle tips.

Pressed by the thumb or with a simple handheld applicator that spreads force evenly, the needles slip into plant tissue and dissolve within about a minute, releasing their microbial cargo.

In laboratory tests, the patch barely disturbed plant tissue or function. Shallow indentations in leaves faded within two hours; chlorophyll readings remained stable; and stress-response gene expression, which briefly rose after insertion, returned to baseline within 24 hours. The patches maintained high microbial viability after storage for up to four weeks – meaning the patches can be prepared in advance – and importantly, loading concentration translated to delivered dose, which enables controlled application that is difficult to achieve in soil.

A 3D-printed applicator provided uniform insertion across large leaf areas and could become an integral component in future robotic automation.

Proving the approach

The research team demonstrated that delivering a plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) cocktail of Streptomyces and Agromyces-Bacillus through leaves or stems improved growth in Choy Sum and Kale compared to untreated controls and gave better results than soil treatments with microbes. PGPR is commonly used to improve nutrient uptake and stimulate growth hormones in plants.

Additionally, the plants grew more as the researchers loaded more microbes into each patch, up to an effective ceiling. Beyond that, extra microbes did not help the plants grow further. This lets growers determine the lowest effective dose, which in turn cuts costs and waste.

“Our microneedle system successfully delivered biofertilisers into Choy Sum and Kale, enhancing their growth more effectively than traditional methods while using over 15 per cent less biofertiliser,” Asst Prof Tay said. “By faster growth we refer to higher total plant weight, larger leaf area and higher plant height.”

The team tracked the bacteria as they moved from the injected leaves to the roots within days. At the roots, the bacteria nudged the root microbiome towards a more beneficial mix without throwing it out of balance. Plant chemical readouts showed that the main energy-production cycle (cells turning sugars into usable energy) was working harder, nitrogen was used more efficiently and compounds needed for growth were synthesised at a higher rate. The team also observed stronger antioxidant capacity, a sign the plants were better prepared for stress and growth.

Scaling and applications

The team extended the approach to beneficial fungi. Patches loaded with a Tinctoporellus strain (AR8) promoted Choy Sum growth and adjusted phytohormones levels – the signalling molecules that guide how plants grow, develop, and respond to their surroundings – helping to keep plant growth hormones in balance.

“This work is the first to demonstrate that root-associated biofertilisers can be directly delivered into a plant’s leaves or stems to enhance growth,” said Asst Prof Tay. “With this finding, we introduced a new concept of ‘microneedle biofertilisers’ that overcomes significant challenges of soil inoculation.”

The researchers see early applications in urban and vertical farms where precise dosing matters, as well as in slow-growing, high-value crops such as medicinal herbs.

“A major focus is scalability,” Asst Prof Tay said. “We plan to explore integrating our microneedle technology with agricultural robotics and automated systems to make it feasible for large-scale farms. We will also test this across a wider variety of crops, such as strawberry, and investigate how these microbes migrate effectively from the leaf to the root.”