Follow CDE

PDF Download

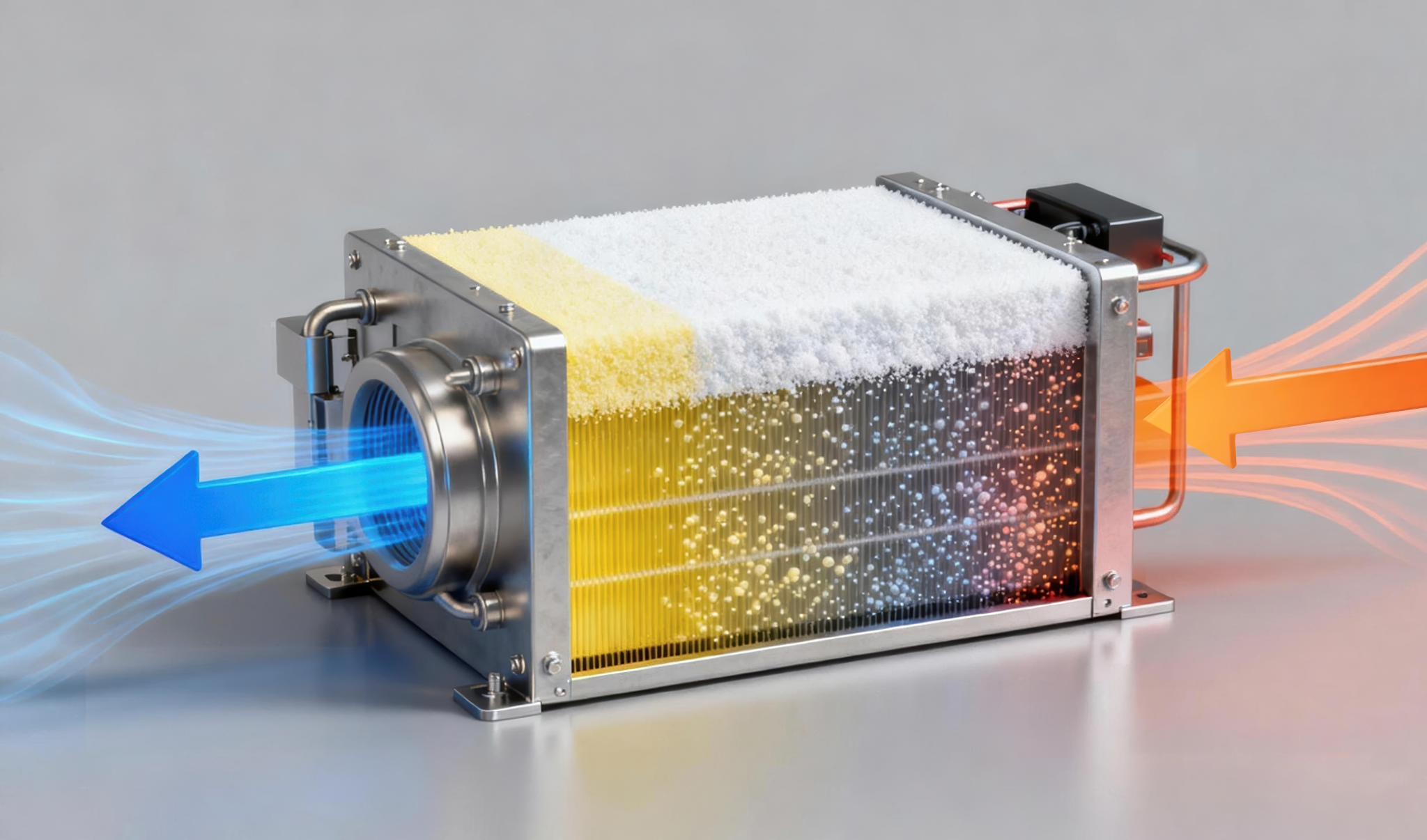

A new heat exchanger design combines condensation and desiccant processes to manage humidity more efficiently, reducing energy use without sacrificing comfort.

In Singapore, about a quarter of household electricity use goes to cooling, and a significant portion of that energy is spent not on lowering temperature, but on removing the air’s moisture. It is an unseen burden in the tropics, where latent cooling — the energy needed to dehumidify the air — can make up to 50% of total cooling demand. As the region warms and humidity rises, that share is expected to grow.

Most air-conditioning systems deal with moisture by overcooling the air until water condenses on chilled coils, then reheating it to a comfortable temperature. It is also very wasteful as too much energy is lost in the cycle of cooling and reheating. Associate Professor Ernest Chua from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, wondered whether there might be a smarter balance. One that could tame the tropics’ moisture without driving temperatures so low.

Associate Professor Ernest Chua and his team designed a new heat exchanger that combines condensation and desiccant processes to manage humidity more efficiently.

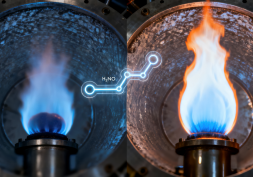

His team turned to desiccant-coated heat exchangers, or DCHEs. These devices can remove moisture in two ways: by condensation, as in conventional systems, and by sorption, where a desiccant layer chemically locks in water vapour from the air. “Conventional systems depend almost entirely on condensation, which means the coils have to run much colder than necessary,” says Assoc Prof Chua. “If we can harness both condensation and sorption, we can achieve the same level of comfort at warmer coil temperatures — and that’s a big step toward greater efficiency.”

The team’s study, published in Energy, investigates how DCHEs behave under below-dew-point conditions — a regime where condensation and sorption occur together. Most prior studies examined only sorption, leaving a gap in understanding how the two processes interact and how to select desiccant materials that remain stable when condensation is present.

A new guide for below-dew-point cooling

To fill that gap, the researchers developed a three-step guide for evaluating desiccant materials and operating conditions below the dew point.

The first step tests stability, exposing a coated heat exchanger to long cycles of extreme, condensation-heavy conditions to see if the material breaks down or dissolves. The second step identifies the transition temperature — the point at which dehumidification shifts from being dominated by condensation to being driven primarily by sorption. The final step examines how factors such as inlet humidity, air contact time and switching time affect system performance.

To demonstrate the process, the team used a composite superabsorbent polymer–lithium chloride (SAP–LiCl) coating. It proved highly stable even in the presence of water, maintaining its structure and dehumidification ability after extended testing. The researchers determined that the transition between condensation- and sorption-dominant behaviour occurred around 15°C, a temperature range suitable for air-conditioning systems operating just below the dew point.

“This transition temperature is critical,” explains Assoc Prof Chua. “It tells us exactly when a desiccant begins to contribute meaningfully to dehumidification. If the operating temperature sits on the right side of that boundary, the system can work more efficiently without sacrificing comfort.”

The findings showed that the DCHE could remove nearly four times more moisture from air than a conventional condensation-only coil. It could also match or surpass a conventional coil’s dehumidification performance using coolant roughly 5°C warmer. That difference, though small, translates into large energy savings, as warmer coils raise evaporator efficiency and reduce chiller load. Under optimised conditions, the researchers estimate an improvement of about 20% in energy use.

From laboratory concept to working prototype

To test the concept in a full system, the team built a desiccant-coated heat pump (DCHP) prototype.

“Once we understand how sorption and condensation interact, we can design cooling systems that perform well in real conditions they face, not just in the laboratory.”

“Once we understand how sorption and condensation interact, we can design cooling systems that perform well in the real conditions they face, not just laboratory.”

The design alternates two coated heat exchangers between evaporator and condenser roles — one coil cools and dries the air, the other releases stored moisture and prepares for the next cycle.

The prototype delivered a cooling capacity of 1.5 kW (about the output of a typical air-conditioner for a small room) and produced almost five times more cooling energy than the electricity it consumed. The team also found that a 15-minute switching cycle provided the best balance between efficiency and dehumidification. Raising the evaporator temperature from 12°C to 18°C reduced cooling output but increased energy efficiency by roughly 50%, which offers flexibility depending on operational needs.

“Once we understand how sorption and condensation interact, we can design cooling systems that perform well in the real conditions they face, not just in the laboratory.”

The implications are significant for humid places like Singapore, where the energy spent removing moisture from the air accounts for up to half of total cooling demand. Importantly, the combined condensation-sorption approach demonstrated by the researchers could support humidity control in settings that depend on precise moisture management, from commercial buildings and offices aiming to reduce chiller loads, to data centres protecting sensitive hardware, to hospitals and pharmaceutical facilities that rely on stable indoor conditions. Even industrial drying processes, such as food or textile production, could benefit from pre-dried intake air and more efficient heat recovery, underscoring the wider role for DCHEs in improving comfort and efficiency across a multitude of environments.

Moving forward, the researchers plan to apply the same framework to other advanced materials. Among the most promising are metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), crystalline compounds whose tuneable porous structures make them highly effective at capturing moisture. Recognised in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their versatility in catalysis and gas storage, MOFs could extend the performance of DCHE systems even further.

“Ultimately, this is about using materials thoughtfully,” says Assoc Prof Chua. “Once we understand how sorption and condensation interact, we can design cooling systems that perform well in the real conditions they face, not just in the laboratory.”

Read More

View Our Publications ▏Back to Forging New Frontiers - December 2025 Issue

If you are interested to connect with us, email us at cdenews@nus.edu.sg