TRIBUTE TO MENG TA CHEANG (3 MAR 1937 – 25 AUG 2025)

Mr. Meng Ta Cheang, the Academic Director at the School of Architecture from 1983 to 1986 and a distinguished planner and architect, passed away on 25 August 2025 in Brixham, United Kingdom.

Mr. Meng’s planning and architecture careers were closely connected to the design of Kent Ridge campus of the University of Singapore (SU), now the National University of Singapore (NUS). His firm in the Netherlands, OD205, had completed the initial campus plan and guidelines by June 1970, and appointed him to work out details and to coordinate with the local work team. Meng arrived in Singapore in December the same year, and eventually realized the “network of architectural systems set upon the ridge lines” that is now a world-ranked university. In June 1976, the Faculty of Architecture became the first faculty to move into the campus. Meng made Singapore his home base until he moved to the United Kingdom between 2017 and 2018.

Meng was born in Peking (present-day Beijing) in 1937, and travelled with his family to Taiwan subsequently. He had wanted to study engineering, but chose architecture at the National Cheng Kung University at his uncle’s suggestion, graduating in 1958. His graduating design project, an airport, forecasted his ability to weave together complex functions and spatial forms. After further studies at TU Darmstadt, he joined OD205 in Holland in 1965 and worked on various master plans and designs for campuses and medical facilities.

A series of campus design commissions followed the completion of SU campus, including the Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember in Surabaya and Hasanuddin University, both in Indonesia. Knowledge and experience accrued from past campus designs were applied to new ones, as was the case in the design of SU campus. For example, he designed and built cast in-situ shading devices for double volume spaces at Hasanuddin University, where there was no budget for them at SU. Other unbuilt features at Kent Ridge included travelators to connect lower levels to the “yellow-ceiling” circulation spine, as well as a pedestrian bridge to connect Yusof Ishak House with the Faculty of Medicine near ridge level.

Fig. 2: The cluster of mature trees kept in the designing of Kent Ridge campus, opposite the Central Library (photo by author)

Fig. 2: The cluster of mature trees kept in the designing of Kent Ridge campus, opposite the Central Library (photo by author)

Fig. 3: Path between SDE and Central Library (photo by author)

Fig. 3: Path between SDE and Central Library (photo by author)

It was at SU that he was able to plan in relation to natural environments in a large tropical location. As the gridded linear blocks negotiated the winding ridge lines to the lower elevations, Meng made sure that almost all mature trees were retained and used materials like overburnt brick where required, at ground level. To him we owe the commodious semi-verdant settings all over the current NUS campus, especially around the SDE blocks and Techno Edge canteen.

Over a fifteen-year period since the mid-1980s, Meng was a crucial planner for the Overseas Chinese Town in Shenzhen, China. After touring its landscapes and its existing structures including old houses, he was famously remembered by those present as the person who halted the bulldozers that had earlier been mobilized on site, and reconfigured its planning to maintain crucial landscape and heritage features. It pointed to new directions and mindsets in planning whose importance had percolated to many of China’s planners in the present-day. The Overseas Chinese Town is now an exemplar in sustainable planning worldwide.

When the Singapore Institute of Architects was invited by the Ministry of National Development to design its first two Design Guide Plans in 1989, Meng led the team for Simpang and proposed a sustainable town that could continue to grow and develop. Natural features like the waterways and irregular coastlines of the northern area were used to accentuate the design, and cluster housing and other mixed-use forms in four clear zones would create a sensible waterfront development, something that has continued relevance with the recent announcement of plans to develop northern Singapore.

In Singapore, Meng worked on many architecture projects in education. These included CHIJ Katong Convent, Chinese High School and Yishun Junior College. His design for the Outward Bound School at Pulau Ubin enabled school goers to engage a rugged learning environment amidst natural landscape. He designed several community centres including the ones at Mountbatten and Tampines West.

Meng was an early pioneer in conservation work that officially began in Singapore in 1989. His major projects included historic structures like the Yue Hwa store that reoccupied the famous Great Southern Hotel (or Nam Tin to most) at Eu Tong Sen Street, after the 1927 building was restored by OD205. Several shophouses belonging to the medical shop Eu Yan Sang along South Bridge Road were also restored contemporaneously. For the townhouses at Bukit Pasoh, Meng successfully challenged the stringent fire regulations and used retractable staircases for the back of the respective units.

Due to his vast travels and experiences, Meng was conversant in fifteen Chinese dialects, and fluent in English, Dutch, German and Mandarin (and some Tamil). He sketched wherever he has travelled to; the expressive line work capturing the essences and natures of those places. Then there is his Chinese calligraphy, evidenced by the many works shown to me and others whenever one visited his home at Oriole Crescent, the last before he left for UK.

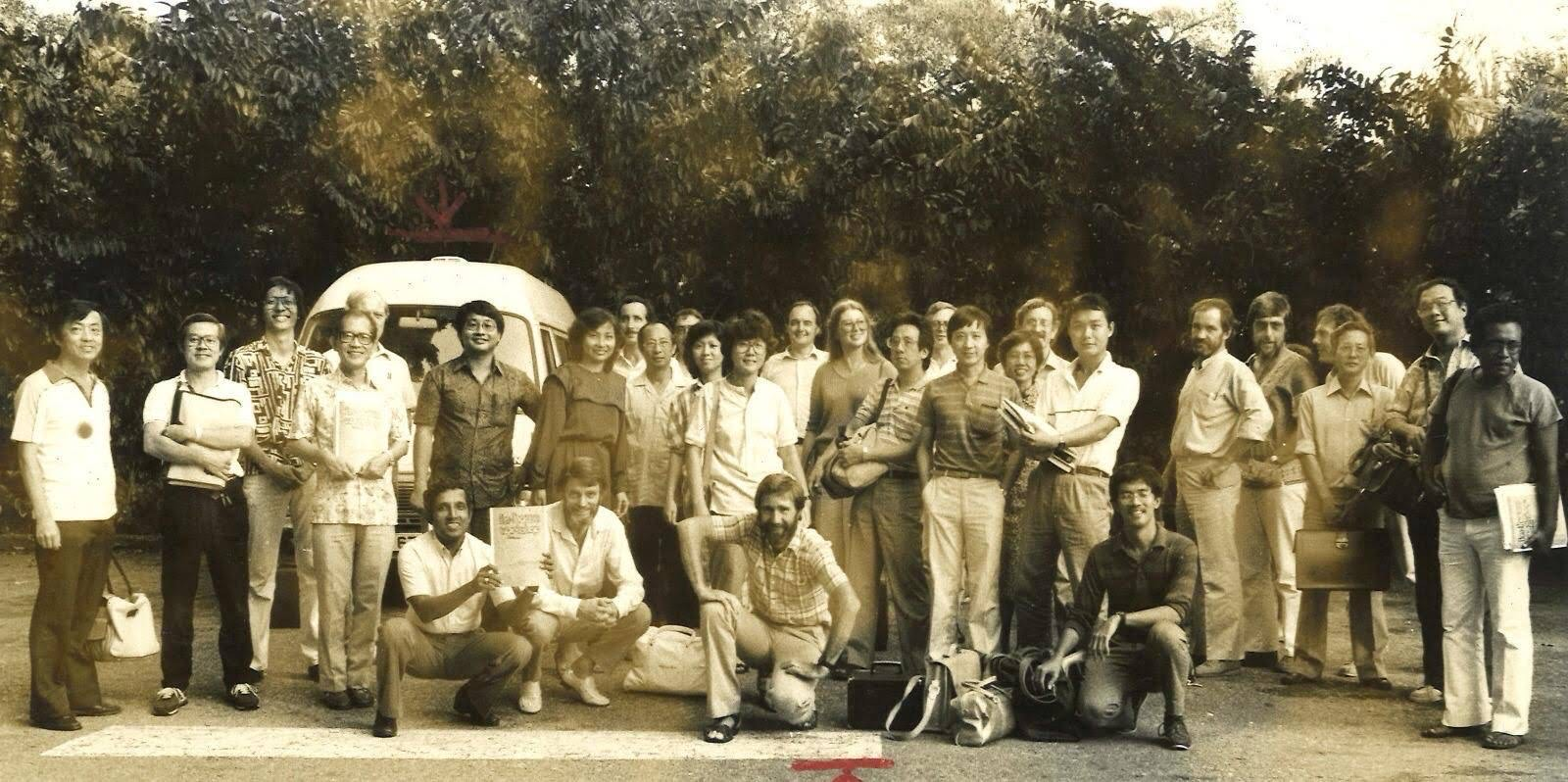

He once told me that as Academic Director at the School of Architecture, he felt it was important for the various academics and staff to work together as a group. To that end, he started retreats outside of campus to energize and strategize people and curricula, respectively, as well as made sure he met staff over lunch or dinner on a regular basis. In 1984, he pushed for the school to adopt the RIBA 3+1+2 system such that, as he put it, “our graduating students will be employable not only in Singapore, but overseas.” He tried to get the design tutor to student ratio to 1:8 for studio groupings, but only managed to bring it to 1:12.

Fig. 4: Meng during a campus visit on 21 June 2009, next to a Tembusu tree he had retained. (photo: author)

Fig. 4: Meng during a campus visit on 21 June 2009, next to a Tembusu tree he had retained. (photo: author)

Meng’s first planning work in Singapore was in 1966, a few years before his SU campus involvement, when he participated in the Singapore Masterplan prepared at that time by the Planning Department with input from international experts including those from the United Nations. He is thus conversant about the development history of Singapore as a valuable contributor and participant since post-Independence planning commenced.

Like so many others, I learnt the histories of Singapore’s planning, architecture and conservation through his astute observations and critical perspectives, something that is still useful in my work. His affable and sincere personality in his interactions with others, were what made him a great person, above and beyond that of a distinguished designer and educator. He will be missed by all who knew him, and those whose lives he influenced.

Lai Chee Kien, 2 Sep 2025