Mechanical Engineering

Fuelling the future of sustainable shipping

Follow CDE

PDF Download

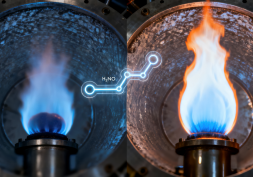

A new engine concept turns ammonia into its own source of hydrogen, charting new waters for cleaner, more efficient shipping without the need to store hydrogen onboard.

Each year, international shipping moves over 80% of global trade and emits around one billion tonnes of greenhouse gases. Heavy fuel oil remains the industry’s workhorse, prized for its reliability and energy density but notorious for its carbon footprint. As the International Maritime Organization pushes toward net-zero emissions by 2050, the search for viable carbon-free fuels is on.

Associate Professor Yang Wenming (left) and Dr Zhou Xinyi (right) introduced a new concept for an ammonia–hydrogen engine with a single ammonia fuel supply.

Among the candidates, ammonia has been in the spotlight. It is carbon-free, easily liquefied for transport and can be produced on a large scale through well-established industrial routes. It also carries a high concentration of hydrogen by volume — a property that makes it an attractive hydrogen carrier. However, ammonia is difficult to ignite, burns slowly and tends to leave behind unburned fuel and nitrogen oxides that harm efficiency as well as the environment.

Hydrogen, by contrast, burns quickly and cleanly, and blending it with ammonia improves both performance and emissions. Its storage requirements, however, are its Achilles’ heel. Hydrogen must be chilled to -253°C or compressed at high pressures, requiring bulky, costly tanks — impractical for long voyages at sea.

This long-standing dilemma — how to capture the best of both fuels without their drawbacks — is what Associate Professor Yang Wenming and Senior Research Fellow Dr Zhou Xinyi from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore set out to address.

Their study, published in Joule, introduces a new concept for an ammonia–hydrogen engine with a single ammonia fuel supply. In essence, the engine makes its own hydrogen as it runs, avoiding the need to carry a separate supply altogether.

Turning fuel into its own catalyst

Most ammonia-hydrogen engine concepts today rely on external reformers: separate reactors that heat ammonia to around 550°C and use catalysts such as ruthenium to break it down into hydrogen and nitrogen. These systems consume additional energy for heating, add mechanical complexity and occupy valuable space. They also face trade-offs between cost, conversion rate and durability, all of which are critical for ship engines expected to run continuously for decades.

“Instead of processing ammonia outside the engine, we thought that we could produce hydrogen inside the engine cylinder itself.”

“Instead of processing ammonia outside the engine, we thought we could produce hydrogen inside the engine cylinder itself.”

“Instead of processing ammonia outside the engine, we thought that we could produce hydrogen inside the engine cylinder itself,” says Assoc Prof Yang.

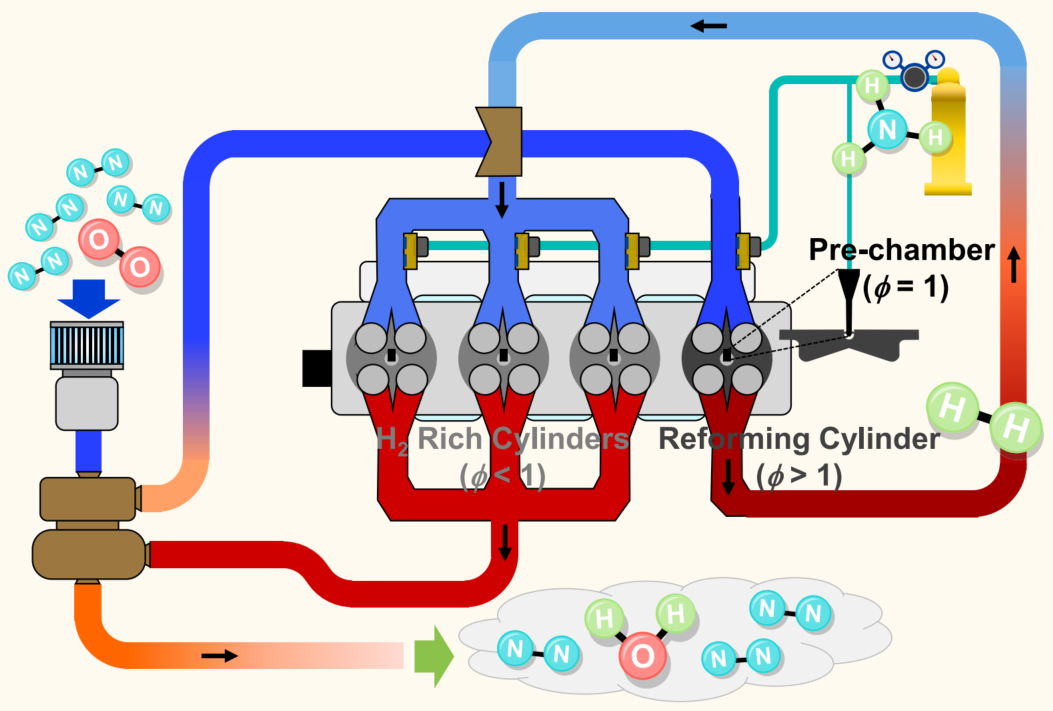

In the team’s concept, one cylinder in a multi-cylinder engine operates on a fuel-rich ammonia mixture. Under the intense temperature and pressure of combustion, part of the ammonia decomposes into hydrogen. This hydrogen-rich exhaust is then recirculated to the other cylinders, enriching their combustion and improving efficiency — all using the same fuel.

“Instead of processing ammonia outside the engine, we thought that we could produce hydrogen inside the engine cylinder itself.”

To keep this process stable, the researchers introduce an active prechamber ignition system. It ignites a small, easily combustible mixture in a prechamber, sending high-temperature turbulent jets into the main chamber to ignite the ammonia-rich fuel. This ensures reliable ignition without relying on pilot diesel, thereby averting carbon dioxide emissions from fossil-based ignition fuels.

“More importantly, integrating active pre-chamber technology can extend the ammonia-rich limit of the main chamber, thereby increasing the total hydrogen production,” says Dr Zhou.

Initial experiments and simulations suggest that this in-cylinder reforming approach could improve thermal efficiency, cut unburned ammonia and significantly reduce nitrous oxide emissions, which is one of the key environmental challenges for ammonia engines as the nitrous oxides are approximately 273 times more potent than carbon dioxide in terms of warming the planet.

“The concept also simplifies the system. No bulky reformers, no expensive catalysts and fewer energy losses,” adds Assoc Prof Yang.

Charting new waters

Assoc Prof Yang and Dr Zhou’s work is a step toward making hydrogen practical at sea. His team’s analysis also reveals an important balance: more hydrogen is not always better. Once the hydrogen fraction exceeds roughly 12% of the engine’s energy input, the efficiency gains level off while combustion temperatures, and thus nitrous oxide emissions, rise. The proposed configuration, where one reforming cylinder supports three combustion cylinders, achieves an effective hydrogen mix without affecting emissions.

The researchers also outlined some pertinent challenges that need to be resolved. The physics inside the reforming cylinder are complex, governed by fast-changing flows, turbulent reactions and shifting temperatures and pressures. Understanding how hydrogen forms and behaves under such transient conditions will be key to refining the design.

They also highlighted several possible future directions. For instance, oxygen-enriched combustion could extend the limits of ammonia-rich operation, especially since ships already carry air-separation systems. High-pressure direct injection of liquid ammonia may help improve conversion efficiency near cylinder walls. Moreover, coupling the setup with a small supplementary reformer downstream — powered by the engine’s own exhaust heat — could further raise overall efficiency without increasing system size.

To advance their line of research, the team plans to build the first prototype in-cylinder reforming gas recirculation engine with the support of a major project from the Singapore Maritime Institute (SMI), then validate this technology route in both laboratory and onboard demonstrations, and advance its commercialisation.

“Shipping decarbonisation will require many complementary solutions,” says Assoc Prof Yang. “But if we can design engines that generate hydrogen from the very fuel they burn, we can overcome one of the largest practical barriers — hydrogen storage — and chart a course toward a zero-carbon maritime sector.”

Read More

View Our Publications ▏Back to Forging New Frontiers - December 2025 Issue

If you are interested to connect with us, email us at cdenews@nus.edu.sg