Follow CDE

PDF Download

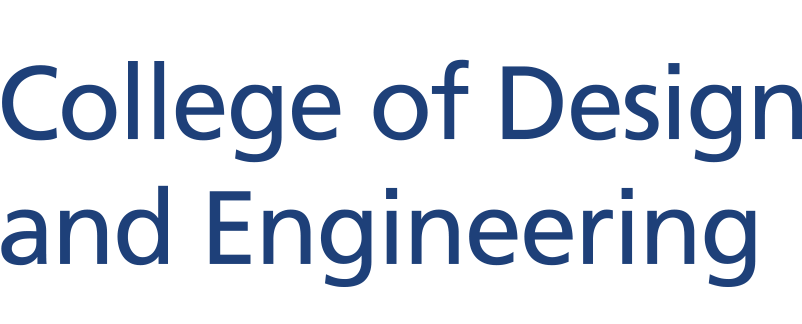

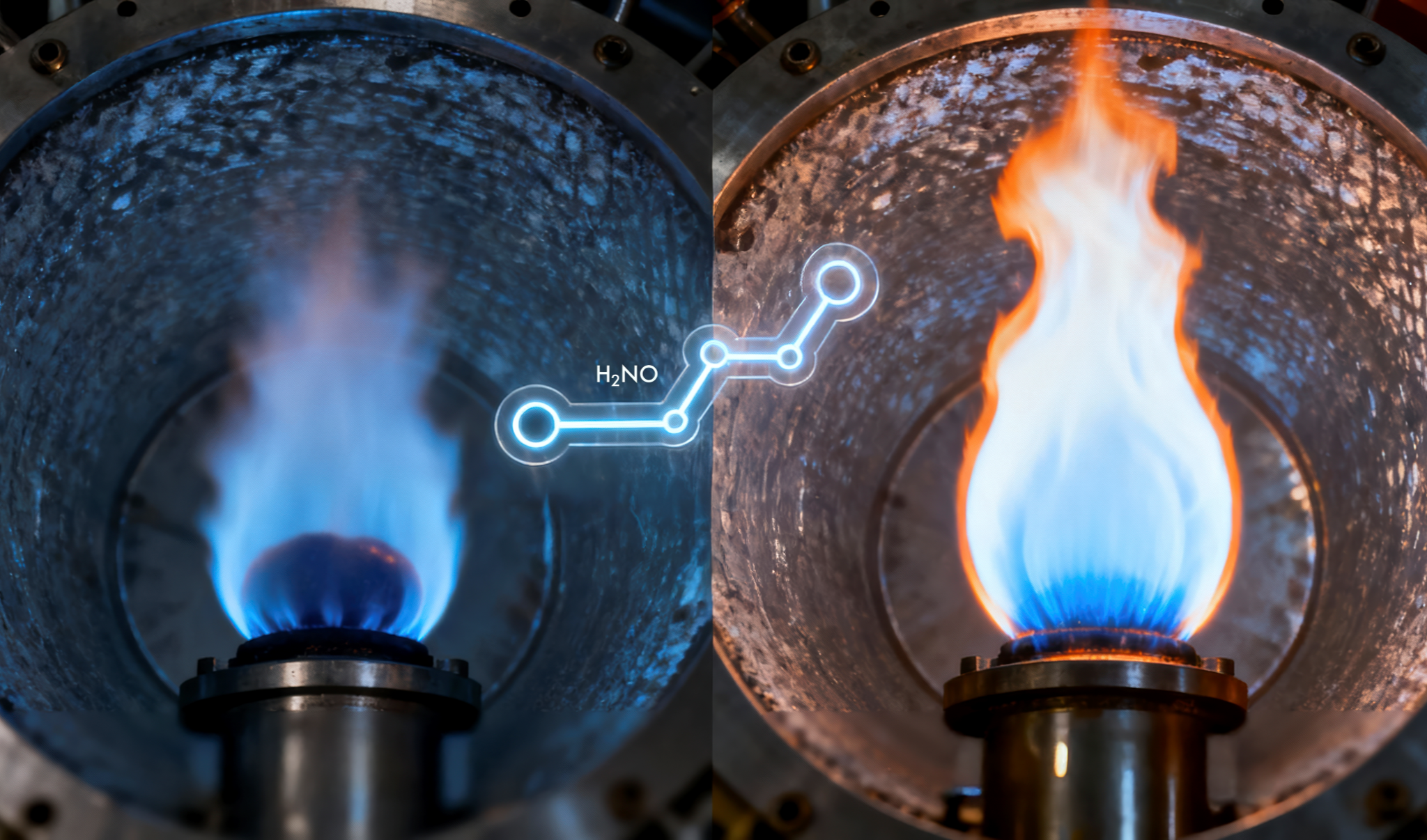

The chemistry of ammonia flames shows that even a small dose of hydrogen can turn an unstable or near-extinction flame into a steadier source of clean power.

Associate Professor Zhang Huangwei led a team to explore exactly where an ammonia flame stabilises, weakens or quenches under engine-relevant conditions

Ammonia may be packed with hydrogen, nature’s lightest and most energy-dense carrier, and contain no carbon, but it is an oddly obstinate fuel. It ignites slowly, burns unstably and easily blows out — a temperamental quality that makes engineers skittish about using it in real turbines or engines. Yet its potential is too valuable to ignore. Finding out when and how ammonia keeps burning, especially under the intense pressures of real combustion systems, could help turn it into a practical low-carbon energy carrier.

Associate Professor Zhang Huangwei from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, wanted to uncover what lies between a stable ammonia flame and a fickle one.

His team’s study, published in Combustion and Flame, used a detailed simulation model known as a premixed counterflow flame — a controlled setup where two opposing jets of fuel and air meet head-on, imitating how flames behave inside engines. By recreating these conditions at high pressures up to 25 atmospheres, similar to those in actual gas turbines, the researchers could explore exactly where an ammonia flame stabilises, weakens or quenches under engine-relevant conditions.

The sweet spot

The team’s simulations revealed that ammonia’s struggle lies in its heat balance. When too much energy radiates away from the flame, the reaction slips into a “weak flame” — a cooler, slower-burning state that exists only within a narrow range of flow conditions. It glows faintly but stays alive, surviving where most flames would fade.

Adding hydrogen, however, changes the picture. Even a small fraction of about 10% by volume injects a strong dose of resilience. It triggers a low-temperature chemical route, known as the H2NO pathway, that helps the flame recover lost heat and stay alight. In the process, hydrogen dramatically widens ammonia’s burning limits, the range of mixtures and pressures in which the flame can sustain itself. Under these conditions, the flame can endure where pure ammonia would have long been snuffed out.

By laying out these flame transitions, Assoc Prof Zhang’s team produced a comprehensive regime map that shows where different flame modes appear and vanish. Such maps are invaluable to turbine designers, who must ensure that combustion remains stable under constantly changing loads and airflow patterns. They also reveal how fragile the balance is between temperature, pressure and chemistry — and how a touch of hydrogen can stabilise the system.

“A small dose of hydrogen goes beyond making it burn faster — it keeps it from dying out.”

“A small dose of hydrogen goes beyond making it burn faster — it keeps it from dying out.”

“Ammonia carries energy cleanly, but the real challenge is keeping the flame in its sweet spot when pressure and heat loss conspire against it,” adds Assoc Prof Zhang.“ A small dose of hydrogen goes beyond making it burn faster — it keeps it from dying out.”

The team’s next steps involve refining radiation models to capture reabsorption effects — how some emitted heat is recycled back into the flame — and incorporating sensitiser species to modulate the reactions of ammonia flame chemistry.

“A small dose of hydrogen goes beyond making it burn faster — it keeps it from dying out.”

From fundamental chemistry to future energy systems

The team’s findings form part of Singapore’s Low-Carbon Energy Research (LCER) Programme, a national initiative that supports research and development of emerging low-carbon energy alternatives that have the potential to help reduce Singapore’s carbon footprint.

Assoc Prof Zhang leads a larger project that couples ammonia cracking — breaking the molecule into hydrogen and nitrogen — with gas-turbine combustion and waste-heat recovery. Supported by the LCER Programme, the project aims to design integrated systems that can generate power efficiently while keeping nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions low.

Other strands of the project span fundamental chemistry to system-level design. On one front, researchers are developing catalytic models and laboratory reactors to improve ammonia cracking efficiency — partially splitting ammonia into hydrogen and nitrogen to create a more reactive, lower-emission fuel stream. On another, teams are using laser-based diagnostics to probe how these cracked fuels behave in gas-turbine flames at both atmospheric and elevated pressures. Parallel efforts tackle the engineering and economic facets: assessing energy efficiency, waste-heat recovery and the techno-economic feasibility of combining cracking and combustion in a single integrated system.

Together, these efforts move toward pilot-scale gas-turbine demonstrations, where the goal is to prove that ammonia, when intelligently cracked and combusted, can deliver stable power generation with minimal nitrogen-oxide emissions.

Read More

View Our Publications ▏Back to Forging New Frontiers - December 2025 Issue

If you are interested to connect with us, email us at cdenews@nus.edu.sg