Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

Making ammonia burn cleanly at industrial heat

Follow CDE

PDF Download

A single-atom platinum catalyst lights ammonia at 200 °C and keeps it burning steadily at 1,100 °C with low NOx, generating high-grade, carbon-free heat for steel, cement and chemicals.

Ammonia is a tempting fuel for the world’s hottest jobs. It can be made from air, water and renewable electricity, stored as a liquid and shipped using know-how industry already has.

However, the snag is that it is stubborn to ignite, burns sluggishly and tends to spew nitrogen oxides (NOx), when pushed to high temperatures. That mix has kept heavy industry — where high-grade heat is non-negotiable — tethered to fossil fuels.

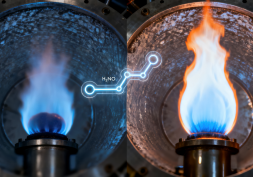

Professor Yan Ning (left) and Assistant Professor He Qian (right) led a group to design a catalyst that gets ammonia burning just above 200°C and sustains clean combustion at 1,100°C.

CDE researchers have now shown that design at the atomic scale can change the equation. In work published in Joule, a team led by Professor Yan Ning from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and Assistant Professor He Qian from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering designed a catalyst that gets ammonia burning just above 200°C and sustains clean combustion at 1,100°C. Importantly, it converts the fuel completely into nitrogen and water, with only trace amounts of NOx. This means that industries could one day use ammonia to generate high-grade heat without producing carbon dioxide or harmful exhaust gases.

Why ammonia heat has been hard to harness

Industrial furnaces and reactors need intense, controllable heat delivered on demand. In principle, ammonia can provide that without carbon. But in practice, it is tricky. Ammonia’s “flammability window” is narrow — it only burns cleanly in a tight range of fuel–air mixes. In addition, the “light-off” temperature — the point where it starts burning readily — is high, and flames can become unstable. When operators raise temperature to keep the flame alive, NOx usually climbs.

“Heavy industry needs high-quality heat, not just a clean exhaust,” says Asst Prof He. “We set out to kill two birds with one stone: make ammonia easier to ignite and keep NOx low when you run it hot.”

The team’s approach, known as high-temperature catalytic ammonia combustion, uses a surface catalyst to help ammonia react with oxygen more easily. The tricky part is finding a material that can not only trigger combustion early, but also withstand the punishing temperatures needed for industrial heat.

“What matters here is the design logic. Pairing a heat-stable support with isolated metal atoms enables us to achieve both early ignition and resilience at extreme temperatures. The system naturally favours the formation of nitrogen over nitrogen oxides.”

“What matters here is the design logic. Pairing a heat stable support with isolated metal atoms enables us to achieve both early ignition and resilience at extreme temperatures. The system naturally favours the formation of nitrogen over nitrogen oxides.”

At lower temperatures, the single platinum atoms help ammonia molecules break apart and recombine with oxygen to form nitrogen and water, the cleanest possible outcome of combustion. At higher temperatures, the structure of the catalyst steers the reaction away from NOx formation. Advanced imaging confirmed that even after 80 hours of operation, the platinum atoms stayed dispersed and active, showing the thermal endurance of the catalyst.

“What matters here is the design logic,” says Prof Yan. “Pairing a heat-stable support with isolated metal atoms enables us to achieve both early ignition and resilience at extreme temperatures. The system naturally favours the formation of nitrogen over nitrogen oxides.”

Asst Prof He adds: “Industries could retrofit their systems with minimal changes, gaining the benefits of clean heat without having to rebuild their plants from scratch.”

“What matters here is the design logic. Pairing a heat-stable support with isolated metal atoms enables us to achieve both early ignition and resilience at extreme temperatures. The system naturally favours the formation of nitrogen over nitrogen oxides.”

At lower temperatures, the single platinum atoms help ammonia molecules break apart and recombine with oxygen to form nitrogen and water, the cleanest possible outcome of combustion. At higher temperatures, the structure of the catalyst steers the reaction away from NOx formation. Advanced imaging confirmed that even after 80 hours of operation, the platinum atoms stayed dispersed and active, showing the thermal endurance of the catalyst.

“What matters here is the design logic,” says Prof Yan. “Pairing a heat-stable support with isolated metal atoms enables us to achieve both early ignition and resilience at extreme temperatures. The system naturally favours the formation of nitrogen over nitrogen oxides.”

Asst Prof He adds: “Industries could retrofit their systems with minimal changes, gaining the benefits of clean heat without having to rebuild their plants from scratch.”

The researchers’ next step is to bring this concept closer to the factory floor. Supported by the NUS Centre for Hydrogen Innovations, the team is preparing for pilot-scale trials using facilities equipped for safe ammonia handling. They aim to test the catalyst in practical setups, such as industrial burners, gas turbines or high-temperature reactors, to see how it performs under real operating conditions.

“Ammonia has always held promise as a low-carbon fuel, but making it truly usable required solving a long-standing chemistry problem,” says Du Yankun, first author of the paper. “Our catalyst shows that it is possible to unlock ammonia’s energy cleanly and reliably. That brings us one step closer to carbon-free industrial heat.”

Read More

View Our Publications ▏Back to Forging New Frontiers - December 2025 Issue

If you are interested to connect with us, email us at cdenews@nus.edu.sg