Hybrid climate modelling has emerged as an effective way to reduce the computational costs associated with cloud-resolving models while retaining their accuracy. The approach retains physics-based models to simulate large-scale atmospheric dynamics, while harnessing deep learning to emulate cloud and convection processes that are too small to be resolved directly. In practice, however, many hybrid AI-physics models are unreliable. When simulations extend over months or years, small errors can accumulate and cause the model to become unstable.

In a new study published in npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, a team led by Assistant Professor Gianmarco Mengaldo from the Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, developed an AI-powered correction that addresses a key source of instability in hybrid AI-physics models, enabling climate simulations to run reliably and remain physically consistent over long periods. The advance makes it more practical to run long-term climate simulations and large ensembles that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive with conventional cloud-resolving models.

“This work constitutes an important milestone in the context of hybrid AI-physics modelling, as it achieves decade-long simulation stability while retaining physical consistency, a key and long-standing issue in hybrid climate simulations. This work could constitute the basis for next-generation climate models, where traditional parametrisation schemes for physics are replaced by AI surrogate models and integrated within general circulation models,” Asst Prof Mengaldo said.

Identifying the problem

In the researchers’ test runs, they found that when hybrid climate simulations broke down, these unstable runs displayed an apparent warning sign whereby the total atmospheric energy rose steadily before the model crashed. Looking more closely, they discovered that this energy surge was accompanied by an abnormal build-up of atmospheric moisture, particularly at higher altitudes.

Further analysis pointed to a specific cause during the simulation process — water vapour oversaturation during condensation. During the simulation, the deep-learning component of the model sometimes allowed air to hold more water vapour than is physically possible. And because water vapour plays a central role in the Earth’s water and energy cycles, even small, persistent errors of such can accumulate over time, eventually nudging long-term simulations into instability.

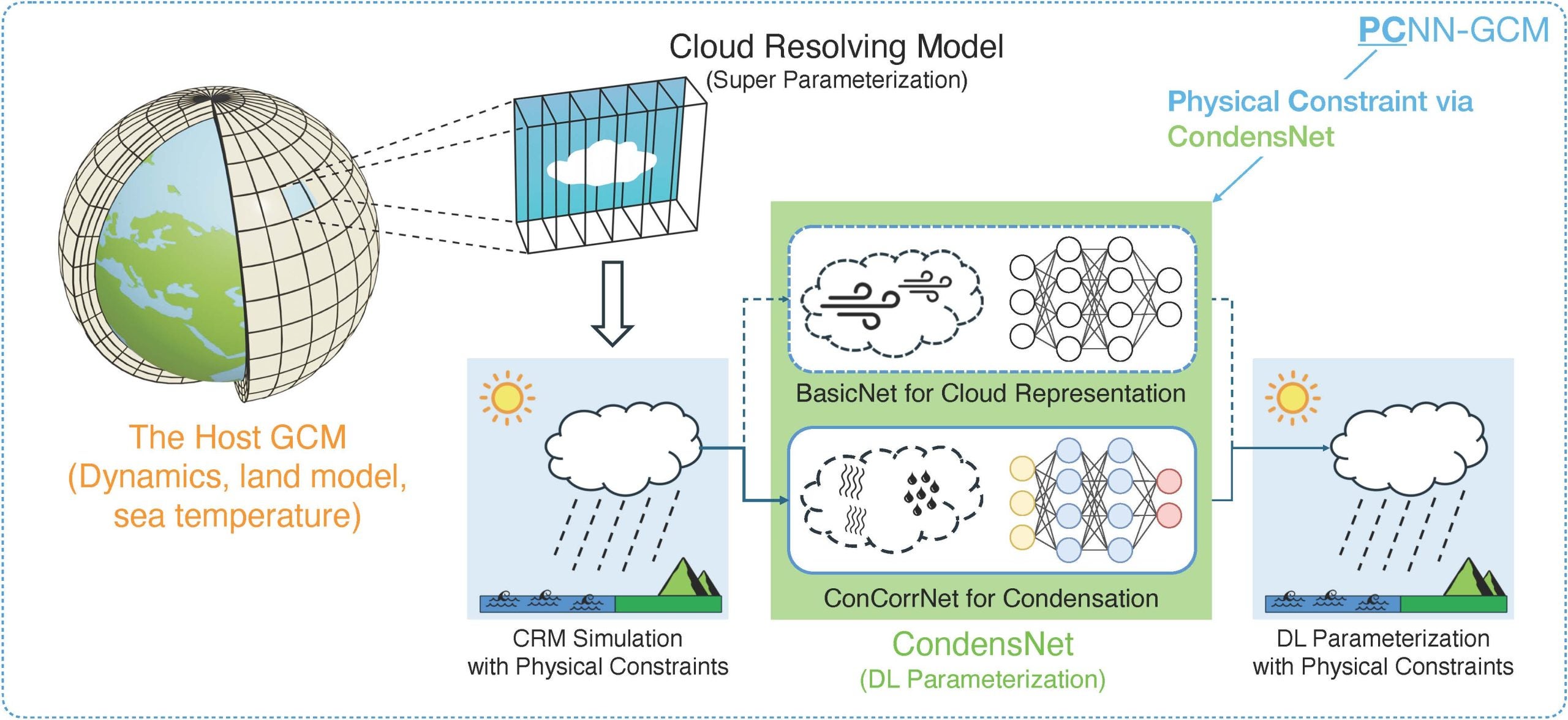

To address this, the team developed CondensNet, a neural-network architecture designed specifically to handle condensation in a physically consistent way. It combines BasicNet, which predicts how water vapour and energy should change within each atmospheric column, and ConCorrNet, a condensation correction module that activates only when the model is at risk of oversaturation, in which humidity exceeds its physical limit.

Instead of applying a blanket rule after predictions are made, ConCorrNet learns from cloud-resolving reference simulations how moisture and energy should be corrected when condensation occurs. When the model approaches oversaturation, the correction is applied locally through a masking mechanism, ensuring that adjustments are limited to the regions where physical limits would otherwise be exceeded.

“It became clear to us that condensation needed its own targeted correction when we observed oversaturation repeating across the failing cases,” added Dr Xin Wang, the research fellow in Mengaldo’s group at NUS, who is the first author of the study. “We designed the constraint to intervene only when the model enters unphysical territory, and to let the correction reflect what the reference physics would actually do.”

The researchers integrated CondensNet into the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM5.2), a widely used global climate model that simulates atmospheric circulation, clouds and energy exchange as part of Earth system modelling. This produced a hybrid framework they call the Physics-Constrained Neural Network GCM (PCNN-GCM). In tests, PCNN-GCM stabilised six neural-network configurations that previously failed, without the need for parameter tuning. The corrected model was able to run long simulations under realistic land and ocean conditions while closely tracking the behaviour of the cloud-resolving reference model.

“This work is the basis of our long-term research vision on hybrid AI-physics modelling, where we plan to develop AI surrogate models of traditional physics parametrisations and interface the overall lightweight hybrid AI-physics climate model with a natural language interface. The latter can turn the model into an AI climate scientist interacting with human stakeholders, and making it more accessible to the broader community,” Asst Prof Mengaldo added.

Designed with the industry and built for real climate workloads

The team’s research was developed as a collaboration among climate scientists, applied AI researchers and high-performance computing (HPC) specialists, with key partners helping to shape both the fundamental science and computing aspects of the work.

Tsinghua University contributed to diagnosing and pinpointing the oversaturation mechanism behind the unstable behaviour in climate simulations, and assisted in algorithmic design, PCNN-GCM implementation, and experimental design.

The NVIDIA AI Technology Centre advised on algorithmic design and performance considerations related to GPU acceleration.

The Centre for Climate Research Singapore (CCRS) contributed expertise in cloud microphysics and climate modelling, supporting the interpretation and evaluation of climate results.1

The team included researchers from Argonne National Laboratory and Penn State University who provided critical insights on climate modelling via machine learning methods.

The research team reported that GPU-accelerated PCNN-GCM can run hundreds of times faster than the cloud-resolving benchmark it emulates, with speedups up to 372 times relative to super-parameterised models in their timing tests, all without the need for large-scale HPC infrastructure. In particular, running six simulated years took about 18 days with a super-parameterised model on 192 CPU cores, compared with just hours using PCNN-GCM accelerated by an NVIDIA GPU.

With both stability and speed in place, the team’s approach makes it more practical to run long-term simulations more often and to scale up ensembles that probe uncertainty and variability — tasks that become extremely more expensive when clouds are instead resolved. The researchers highlighted that CondensNet is not tied to one host model or training source, and it can be ported to other GCMs and trained to emulate other super-parameterisation schemes. In addition, they suggested that the same approach could be extended beyond condensation to other hard-to-resolve atmospheric processes, supporting reliable long-horizon simulations in regions where cloud-related uncertainty remains high.

“Our focus is long-horizon reliability,” added Asst Prof Mengaldo. “If hybrid models are going to be useful, they need to remain stable under real configurations and close to the best reference physics we can train from. This work shows a concrete way to do that for clouds.”

1CCRS is the research arm of the Meteorological Service Singapore and part of the National Environment Agency (NEA). It was launched in March 2013, with the vision to be a world leading centre in tropical climate and weather research focusing on the Southeast Asia region.