Can buildings do better for public health?

In this interview with TK Bean of NUS Cities, NUS professor Lam Khee Poh ponders how the built environment can do an even better job of contributing towards enhancing human health and wellbeing.

Prof Lam Khee Poh, Provost’s Chair Professor of Architecture and the Built Environment at NUS, has more than 30 years’ experience as an educator, researcher, and architect focused on including the principles of total building performance and environmental sustainability in his designs.

TK Bean,

is a full-time teaching assistant at NUS Cities, with a background in urban studies.

Most people are surprised whenever Professor Lam Khee Poh points out that the average office space has a carbon dioxide concentration of 1,000 ppm in the air. That is almost 2.5 times the 420 ppm found outdoors [1]! The concentration in a crowded lecture theatre can go even higher. “Don’t blame my lecture if you’re falling asleep,” he will jokingly tell his students, “it’s the higher concentration of carbon dioxide in the classroom.”

While many people know that the quality of outdoor environments, and their air quality, can impact public health (the United States-based Health Effects Institute estimates that air pollution caused around 8 million deaths globally in 2021 [2]), few have ever given thought to the quality of indoor environments, much less their impact on health. Yet, many people spend a significant amount of time in indoor environments, whether at home, at work, or when visiting malls.

Professor Lam emphasised that if every building incorporated features to improve their indoor environmental quality (IEQ), it would have a huge impact on public health in cities. To achieve this requires methods to measure the impact of buildings, so as to establish suitable design guidelines, create opportunities to demonstrate that these guidelines are feasible, and translate these guidelines into regulations that shape all future developments.

INDOOR ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY (IEQ)

IEQ refers to the environmental conditions inside a building like air quality, acoustics, lighting (natural and artificial), and thermal comfort. Built environment professionals are increasingly interested in IEQ as it impacts the health, well-being, and productivity of a building’s users.

Measure: Total building performance and diagnostics

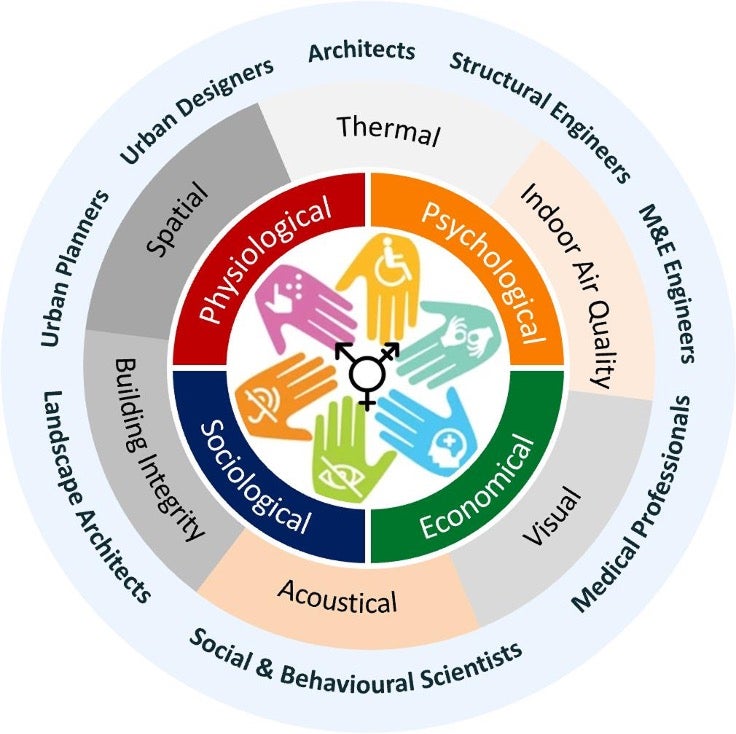

Professor Lam first formally learnt the role that architecture plays in public health while working on his PhD at Carnegie Mellon University in the late 1980s. Academics at Carnegie Mellon were furthering the new concept of total building performance. Total building performance lays out the conditions that buildings should meet to function successfully.

These conditions include meeting the physiological, social, and psychological needs of their users; incorporating flexible elements so that the building can adapt to changing needs and advancing technology; and reducing their environmental impact [3].

Developing diagnostics to measure the above conditions was crucial. As he explained, it is not possible to know how the internal environments of buildings affect people without a way to measure their impact. Previously, one way was to use Draeger pump and sampling tube to take readings of gases like carbon dioxide. Each measurement required a vial that could cost US$10, an amount that could feed Professor Lam’s family for a few days in the early 1990’s!

Nowadays, a whole host of electric sensors are available to measure things like air quality, temperature, and lighting affordably. This enables the taking of real-time measurements, as well as adjusting conditions such as temperature, lighting, and carbon dioxide levels immediately.

With these ways of measurement, studies can then be conducted on how improving IEQ can benefit a building’s users. Studies on indoor air quality have found that improving it reduces employee sick days, enhances cognitive function, and increases productivity [4]. Other studies, focused on indoor lighting, have examined how it impacts internal body clocks and the quality of sleep. These studies have even proposed how to adjust the intensity and colour of lighting in the evening, to help people with trouble sleeping [5].

Organisations also need a way to measure the financial costs and benefits from improving indoor environments. Professor Lam explained that existing organisational structures obscure these benefits. Retrofitting an older building with systems that improve IEQ register as an increase in spending by the organisation’s facilities or infrastructure budget.

One way to make cost savings more visible is to let the people who spend to implement building improvements keep the cost savings. Professor Lam shared that one American university he visited allows their facilities management department to keep any budget they save from implementing energy-saving measures. This incentivised them to further do further research on their own, and to roll out sustainable measures more quickly.

However, the key cost savings occur under human resources, through increased productivity, less sick days, and lower turnover. This means that accounting departments and upper management may not see the related costs savings resulting from a renovation.

He also highlighted the work of the Delos Living Lab. Started by Paul Scialla, a former Wall Street banker, Delos does research that provides evidence for the financial benefits from improved indoor environments. Scialla raised money for his organisation by first calculating how much companies pay per person for wellness. In the US, this adds up to about US$700 per person. Yet, some 80% do not make use of such provision. He then proposed that a one-time expense of $100 per person to renovate their buildings and improve IEQ ensures that 100% of the buildings’ occupants benefit and potentially reduces health-related costs.

“The moral of the story,” Professor Lam notes, “is that, in everything we do, there is huge waste. But a lot of waste happens when we do not look at the effectiveness and efficiency of existing processes.” To justify making the right expenses, there is first a need to measure.

"The moral of the story is that, in everything we do, there is huge waste. But a lot of waste happens when we do not look at the effectiveness and efficiency of existing processes."

Demonstrate: First-hand experience matters

Visitors to the School of Design and Environment 4 (SDE4) at NUS might find Professor Lam giving a tour to visitors from Singapore or abroad. Typically, he would point up to vents in the ceiling to show how the cooling system differs from conventional ones, and to highlight how the architects laid out rooms so as to receive natural light while they remained shaded from direct sun [7].

Building systems for air circulation, cooling, and lighting all have existing standards. While not all these standards have a holistic scientific basis – meaning that they often optimise for one human need without considering others – they have become entrenched in the built environment sector. Practitioners do not readily accept new techniques if they deviate from these standards. Hence, pioneer projects that demonstrate the feasibility of new techniques and standards become crucial to changing their minds.

Tours to these projects are persuasive, as they provide first-hand experience that challenges conventional practitioner’s notions. For example, even though maintaining a building at 27°C in a tropical climate greatly reduces its energy needs, many professionals still think that the temperature is too high to feel comfortable. Taking them to a building like SDE4, that achieves this through augmenting their hybrid cooling system with fans, allows them to experience for themselves how they can feel comfortable at 27°C under the right conditions.

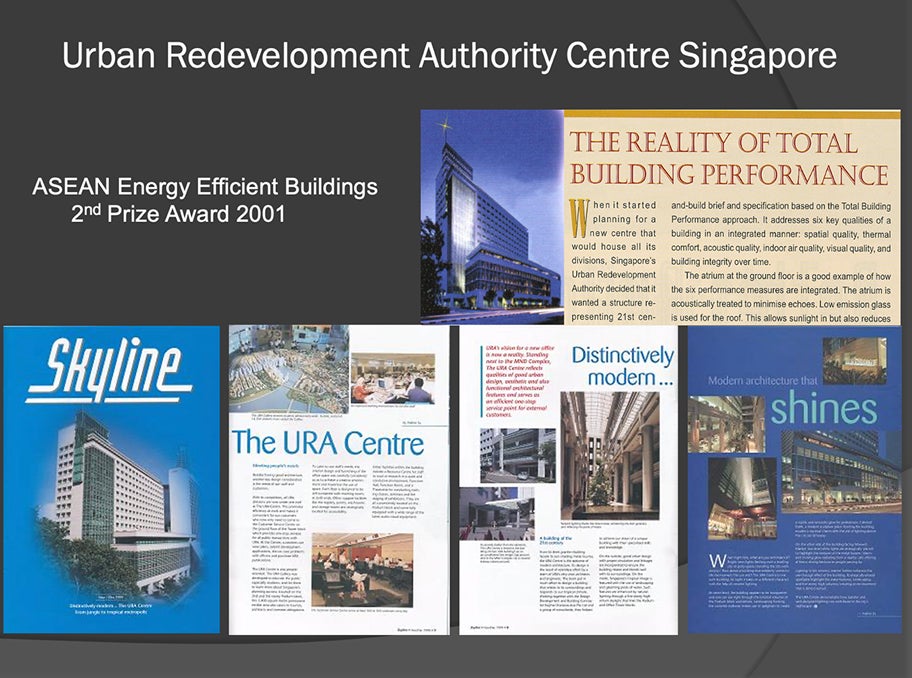

Demonstration projects need respected early adopters who are willing to take risks and finance buildings with innovative measures. In Singapore, the government has become an influential pioneer in adopting new building techniques. The Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) invited Professor Lam to incorporate the principles of total building performance when constructing their new building in 1996, a first in Singapore.

Another example is the National Library Building, opened in 2005, which was the first building to receive the Building and Construction Authority’s (BCA) Green Mark Platinum Award, by pioneering the combined use of various features to reduce energy use. The library has a facade that maximises natural light indoors while minimising incoming heat, uses sensors that help reduce energy usage, and has an air-conditioning system that regulates carbon dioxide levels in each room [8].

Universities in Singapore have also become important early adopters of innovative construction solutions. SDE4 and its neighbouring buildings, SDE1 and SDE3, demonstrate how to design net-positive energy buildings [9] to exist in a tropical climate while remaining cool.

A building that successfully applies systems that improve building performance is not the only thing that promotes the use of new ideas. Once the users and managers of these buildings see that these systems work, they advocate for these systems in other buildings too.

Regulate: Extending best practices to all

Once built environment professionals develop better diagnostic tools and new practices to improve the quality of indoor environments, there is a need to translate these tools into regulations to enforce, or incentivise adoption of, these best practices.

Apart from legislation that enforces minimum standards, such as building codes that require safe levels of carbon dioxide indoors, governments can also adopt certification schemes. This would be similar to how some companies have sought out green certification, like the green building rating system LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), or the BCA’s Green Mark [10], for their buildings to attract eco-conscious employees, many companies now see the value of workplaces designed to optimise the health and wellbeing of their users, to attract and retain talent. Outside of status, certification schemes create a set of standards and practices that clients can articulate to their architects to make their desired buildings possible.

In Singapore, Professor Lam has worked closely with others to support the BCA, as the agency that sets standards for construction processes and buildings, to create – together with the Health Promotion Board (HPB) – the certification scheme called [11] BCA-HPB Green Mark for Healthier Workplaces in 2018. In 2021, BCA updated their Green Mark certification scheme to include the guidelines for health and wellbeing, showing the growing importance of these factors.

Globally, Professor Lam highlighted the important work of the non-profit International WELL Building Institute (IWBI), also founded by Paul Scialla, that built on the findings of the Delos Living Lab to develop the world’s first certification scheme focused on health and wellness.

Professor Lam reminds that architecture should not just intervene in cities, building by building. When architects start by addressing the needs of people, they can then find and implement overarching principles for a better urban environment through architecture.

Future challenges

What more can be done to make buildings healthier and more sustainable? Since many of the buildings applying features that improve IEQ and reduce their carbon footprint are offices, could these technologies and designs become accessible to more people, like low-income communities and factory workers?

Professor Lam thinks that governments have an important role to play in implementing policies that incentivises adoption at-scale to lower the costs of constructing healthier and more sustainable buildings. This can come in the form of subsidies, new requirements for affordable housing projects, and pioneering the adoption of more affordable construction techniques in their projects.

He also emphasised the need to promote passive design. This involves designing buildings so that they can achieve functions like cooling and lighting without using energy. He describes it as “how traditional designers responded when they did not have gadgets and energy-sucking technologies”. These techniques will play a key role in making buildings healthier and more environmentally sustainable whilst remaining affordable.

On research, he notes that more needs to be done to break down the silos between disciplines. Healthier buildings cannot be built if human physiological, psychological, social, and economic needs are considered in isolation from each other. As can be seen from Prof Lam’s work, there is often room to think about how buildings can be better for both their users and the environment at the same time.

He also notes that further research is needed on how the interiors and exteriors of buildings interact with each other to affect people’s health and the environment. This includes how the scenery outside affects people inside, or how lighting from indoor spaces affects people and species outdoors.

Professor Lam continues to take on challenging new projects. He currently works with a Thai green steel company to improve the IEQ of its proposed facilities in Thailand. This creates an opportunity to show how industrial buildings can adopt measures that improve IEQ and energy efficiency. He also seeks to make buildings in the healthcare sector and data centres healthier and more sustainable. He notes that if data centres are not made more energy-efficient, their growing numbers will likely undo any good that has come from the reduction of energy in all other buildings.

As work continues to measure, demonstrate, and regulate to improve the built environment, it is important to remember that people’s needs should always lie at the heart of architecture. Professor Lam explains that, while architects have long argued for the centrality of people’s needs and comfort, architects often must prioritise other considerations, such as the building’s intended function, and minimising construction costs. Greater knowledge and interest in how buildings can improve health, and the environment, fosters opportunity to re-centre people’s needs in architectural practice once again.

References

[1] Building and Construction Authority (2023) UPDATED GUIDANCE NOTE ON IMPROVING VENTILATION AND INDOOR AIR QUALITY IN BUILDINGS FOR A HEALTHY INDOOR ENVIRONMENT. https://www1.bca.gov.sg/docs/default-source/docs-corp-news-and-publications/circulars/updated-guidance-note-on-improving-ventilation-and-indoor-air-quality-in-buildings-for-a-healthy-indoor-environment-by-neabcamoh.pdf

[2] UNICEF (2024, June 18) Air pollution accounted for 8.1 million deaths globally in 2021, becoming the second leading risk factor for death, including for children under five years[Press Release]. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/air-pollution-accounted-81-million-deaths-globally-2021-becoming-second-leading-risk

[3] Hartkopf, V. & Loftness, V. (1999) "Global Relevance of Total Building Performance" Automation in Construction 8, 377-393.

[4] Swope, C. (2023, August 30). What is the ROI for Office Indoor Air Quality Improvements?. Delos Blog. https://delos.com/blog/what-is-the-roi-for-office-indoor-air-quality-improvements/

[5] Benedetti, M., Maierova, L., Cajochen, C., Scartezzini, J., and Munch, M. (2022) “Optimized office lighting advances melatonin phase and peripheral heat loss prior bedtime” Scientific Reports 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07522-8.

[6] vandenAkker, M. (n.d.) Workplace WELLness: How Well-Being Starts with the Building. Workplace Unplugged. https://www.officespacesoftware.com/blog/workplaceunplugged-workplace-wellness-wellbeing-starts-with-the-building/

[7] National University of Singapore Department of Architecture. (n.d.) Net-zero Energy Building. https://cde.nus.edu.sg/arch/facilities/net-zero-energy-building-sde-4/

[8] Yong, CY. (2011) National Library Building (Victoria Street). Singapore Infopedia. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=513772a1-771d-4c18-bbc1-72522ebc0ba7

[9] National University of Singapore Campus Infrastructure. (2022, June 21) Zero Energy and beyond: NUS SDE4 attains Green Mark Positive Energy Award [Press Release]. https://news.nus.edu.sg/zero-energy-and-beyond-nus-sde4-attains-green-mark-positive-energy-award/

10 Building and Construction Authority. (2023, April 11) BCA-HPB Green Mark for Healthier Workplaces. BCA-HPB Green Mark for Healthier Workplaces | Building and Construction Authority (BCA)

[11] Ibid.