Learning to treasure food waste

In this interview with Joshua Ong of NUS Cities, Preston Wong, CEO & Co-founder of treatsure (a company which manages an app platform connecting hotels and grocers with surplus food to everyday consumers) shares insights from leading a sustainability business, and on how the next generation can be inspired to get involved.

Preston Wong,

CEO & Co-founder of treatsure,

is Adjunct Faculty in Sustainability Law at the Singapore Management University’s Yong Pung How School of Law, and Adjunct Lecturer in Sustainability Law & Policy at Yale-NUS College

Joshua Ong,

is a full-time Teaching Assistant at NUS Cities, with a background in history

Preston Wong is best-known for starting treatsure, a company established in 2016, that created an app platform that connects food & beverage (F&B) brands, as well as hotels and grocery suppliers, with the public, to reduce the amount of surplus food going to waste. Since founding the business, Wong, as CEO, has overseen business strategy, development, marketing and operations. Today, treatsure boasts over 100,000 users, and was awarded the National Environment Agency’s (NEA) EcoFriends Award in 2022, and the United Overseas Bank-Business Times Sustainability Impact Leader of the Year in 2023.

How did this journey begin? By the time he started treatsure, Wong had earned a Bachelor of Business Administration degree in Accounting from NUS, and was in the midst of pursuing a graduate degree in law, also at NUS. “I did internships in accounting and law, but I couldn’t see myself in the kind of pressure-cooker environment that I experienced,” he said. “I wanted to find something that could pique my interest intellectually, and could give me joy and purpose”. Looking around at successful startups launched by NUS alumni, he thought that starting a business could be the answer. He recalled: “Looking at the amount of food that was wasted at home, it made me want to prevent more of this waste from happening, and to find a way to provide value for businesses getting rid of food waste.”

The company Carousell was an inspiration, being successful in creating a market for second-hand items. They turned things which were seen as less than desirable into something which even could be considered treasure. Thus, Wong and his fellow co-founder, Kenneth Ham, started treatsure, the company name a play on “treasure” by adding the food-related word “treat”. However, helping potential partner businesses and consumers to appreciate the necessity and value of treatsure was not easy, at first. There were negative perceptions of food waste, and of companies dealing in it, that needed to be overcome.

Recipe for a sustainable business model

The first step was the very decision to make treatsure a for-profit company. “We were very conscious that we could not be a non-profit non-governmental organisation. The image conjured of our work could be one of merely collecting food waste to distribute to those with lower incomes,” Wong explained. Instead, businesses would pay for the benefit of using the platform that treatsure provided. This would be the basis of a sustainable financial model for the company.

For consumers, treatsure had to distinguish itself from the emergence of other food apps such as delivery platforms and discount apps. It had to show how purchasing food on treatsure provided value for consumers, by giving them the opportunity to support a good cause which diverts food from the waste bin, while also giving them savings on food purchases, providing valuable reasons for using their services. “When educating consumers, you also need to deal with concerns about safety and the idea that surplus food is disgusting – for instance, reminding customers that the surplus food being sold on our app doesn’t come from the bin,” he elaborated.

For potential F&B business partners and investors, they had to clarify that they were not a waste collection company, nor turning food into biofuel. They had to position treatsure as a business which would not give food for free. He added: “Treatsure was to be a business that would drive value for F&B businesses, where consumers would pay for the surplus food that was provided by these partner businesses.”

The value of a supportive ecosystem

Instrumental in enabling their fledgling company to grow was the presence of a supportive ecosystem. NUS Enterprise (NUS’ entrepreneurial arm that promotes innovation and startup businesses) provided mentors with experience in entrepreneurship to give good advice to Wong and his team. NUS Enterprise also created the space for Wong and his team to build relationships with broader ecosystem players, through events that brought together the wider startup community. Treatsure set up booths at these events to explain to potential partners what it aimed to achieve. Through this, treatsure was able start partnerships with companies such as DBS Bank.

Government support also came through in a variety of ways. Agencies and ministries would organise events that would procure services from sustainability companies according to the government’s green procurement programme, turning to treatsure to cater food for their events. Treatsure has catered for events organised by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and the NEA. Some agencies profiled treatsure through social media, providing publicity for the company. Treatsure has also obtained funding for joint projects with the government.

Through the support of NUS Enterprise and the government, Wong and his team gained confidence in growing their business and in reaching out to ever-wider audiences of F&B businesses and consumers.

Applying data, shaping behaviour

Along the way, his own understanding of the complexity and depth of the food waste issue evolved. He recalled: “Initially, I thought that the way to address the problem was to address it on the individual level: to find ways to encourage people to finish food and waste less.” However, he came to understand that the problem also arose from the various interests and tradeoffs that different players in the food production and consumption ecosystem had.

“In hotel operations, it does make more sense to prepare food in bigger batches than smaller ones. It provides more buffer, saves on time and manpower, reduces serving time and increases consistency,” he explained.

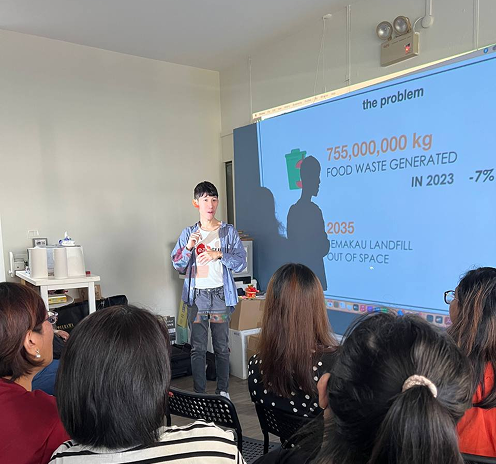

Today, treatsure is fine-tuning its approaches to become even more effective in ensuring that surplus food is valued by consumers. By organising workshops and activities, it is educating the public on the importance of the food waste issue, and how they can play a part in helping.

Sometimes, these are organised in conjunction with the government events that treatsure caters for. “One of the most effective ways of nudging people to embrace surplus food has been through introducing experiential activities,” he said. “Getting people to taste the surplus food helps them to get over the stigma of food which is seen as being on the way to the bin.” Treatsure has also raised awareness through social media, to share with people how food waste can be addressed and framed.

NUS ENTERPRISE

NUS Enterprise helps to nurture entrepreneurial talent in Singapore.

- They design courses and programmes that equip students with entrepreneurial skills.

- They provide resources and networking opportunities to facilitate the development of student-led start-ups.

Wong hopes that treatsure’s operations will be better optimised by using data to understand what drives suppliers’ and consumers’ behaviours, for instance, why there is more surplus food at certain times, or which consumer demographics are more receptive to surplus food.

So far, he and his team have found that young working adults are more receptive, perhaps motivated by the savings provided, or by having better awareness

of the issue of food waste gained through social media.

However, he said, “while consumers have come some way towards appreciating the value of surplus food and the importance of food waste as a sustainability issue in the years since treatsure was founded, I think that there is more progress that needs to be, and can be, made, with regard to changing people’s behaviours - there is still a high food waste rate overall in Singapore.” He hopes that treatsure can continue to play an effective role in creating this change.

How to inspire the next generation

Besides his work leading treatsure, Wong is also involved in educating the next generation. He is currently Adjunct Faculty in Sustainability Law at the Singapore Management University’s (SMU) Yong Pung How School of Law, and Adjunct Lecturer in Sustainability Law & Policy at Yale-NUS College. Through the classroom, he has the opportunity, as he says, to “bring real-world perspective on sustainability practice, share about what is trending, including in areas like climate litigation and sustainability law.”

Sustainability law involves using the courts to attain accountability on environmental problems. Activists can seek to use the courts to change laws and policies by getting them to weigh in on environmental cases and set precedents. Some are successful, and some are not, but the publicity these efforts generate for the cause provides wins either way. As an academic, Wong is engaging with judges, lawyers and practice professionals to keep updated about these trends globally. “It’s exciting, as I can share with students in real-time about new cases on sustainability litigation. It’s a field that is constantly evolving, even as we speak.”

Wong also engages with the government on food waste laws and is part of a Youth Panel under the Ministry of Culture, Community & Youth (MCCY) that brings together young people with a passion for sustainability and gives them the opportunity to develop recommendations for Singapore’s ministries.

Asked how easy or difficult it has been to engage with today’s youth on sustainability, Wong shared that, while there are young people who are very interested, there are also those who have become skeptical of sustainability efforts, either seeing them as mostly greenwashing, or seeing the problem as insurmountable. “You need to convince them that there are some genuine efforts they can get behind,” he advises. This is why he sees his work in education as being of utmost importance. “In the classroom, I can share with them about what is going on, and how they can make a real change. With this, once my students enter the workplace, they will not find that sustainability is foreign to them, but they will be inspired to make a difference.”

What it takes to make a difference

Wong’s experience speaks to the complexity of the issues that complicate the path to a sustainable future: the multitude of causes, stakeholders and impacts that any one issue such as food waste can have.

Yet, at the same time, his work also shows the breadth of what it can mean to work for a sustainable future: it could take the form of starting a business, engaging with the public and the government, and educating and inspiring the youth, among others.

Perhaps, if more can be inspired to find solutions to the problems that cities face today creatively, everyone can look forward to a more optimistic future.