RESEARCH

Are Singapore's new towns now less complex?

Dr Michael McGreevy (Research Fellow, NUS Cities) extols the virtues of neighbourhood planning and design that creates opportunities for flexible use and a wide variety of services and amenities, based on his research into Singapore’s changing approach to its HDB neighbourhoods.

There is a broad consensus within urban studies scholarship that cities are complex adaptive social systems with numerous similarities to complex adaptive (eco) systems in nature such as rainforests and reefs. Complex adaptive systems (CAS) are self-organised systems that exist between the order of the machine and the unconnected disorder of chaos, and are often described as being on the edge of chaos. They exhibit traits such as design without a designer, and a dynamic drawn from the bottom-up activity of multiple diverse, connected and autonomous actors, which drives the evolution of these systems. They are also hierarchical, in that each is made up of a mosaic of subsystems that are, in turn, made up of other overlapping subsystems and so on [2].

In the natural ecosystem of the rainforest, the metabolising of solar energy begins with photosynthesis producing materials that are then cycled and recycled. Ecosystems evolve and grow by successfully cycling increasing amounts of nutrients through a dynamic in which niche agents are continually evolving, seeking out, finding and exploiting nutrient streams, and then creating new streams of nutrients to be exploited by other agents [2][4]. In evolved complex adaptive systems, a long tail of diverse, highly specialised and often brittle niche agents primarily carries out the absorption and exploitation of nutrients. None of these niche agents is individually vital to the system on their own; however, collectively, they provide diversity and richness and biomass.

Not all the subsystems within a city system hierarchy are CAS. Some are ordered mechanical systems. Others are complicated and diverse, but lack inter-agent connectivity, therefore, could be described as chaotic. Others have interconnected diversity, but do not evolve via self-organised adaptive responses; therefore, are complex but not adaptive. Finally, there are those, perhaps most, which combine aspects of the top-down order of mechanical systems, the stable connected diversity of complex systems, and some of the bottom-up self-organisation of CAS.

The CAS of the city includes abiotic elements (buildings, infrastructure, topography) and governance (laws, regulations, standards, rules of thumb, procedures, and socio-economic relationships) within which biotic agents (people, businesses, institutions, communities) act. The degree to which individual agents are bound by top-down rules can determine their autonomy and space for self-organisation. The less space available for endogenous self-organisation, the more ordered the system becomes.

To be complex adaptive systems, the activity centres (transaction places, gathering places) need to have integration via a connected public realm of footpaths, squares, and streets, a built form of diverse premises, and a significant mass of autonomously owned independent businesses and premises operating within this connected and bounded environment. Only the traditional civic and neighbourhood commons (town and high street activity centres) exhibit these, and therefore have the connectivity, bottom-up self-organisation, and evolutionary dynamism required for CAS.

As complex adaptive systems, the traditional civic and neighbourhood commons are manifest with evolved relationships, a catalyst for synergies that have a dynamic tension fuelled by competition, cooperation, and possibilities. These systems offer constant opportunities for niche commercial opportunities which, in turn, drives adaptation, change and dynamic evolution [2][4].

The bulk of the mass of the complex commons is found in a long tail of niche agents. These agents often have low turnover and profitability, and are consequently fragile. Many niche agents are also, in biological parlance, redundant, in that their core functions can be transferred to other agents with minimal effect on the system as a whole. Ongoing survival for fragile niche agents requires hypersensitivity to their environments in order to respond to information in subtle idiosyncratic ways via trial-and-error experimentation. This produces a system dynamic driven by the constant application of the collective intelligence of a multiplicity of embedded agents in pursuit of fresh opportunities.

The redundancy and inherent fragility of niche agents means that they come and go regularly, contribute little to overall turnover, and typically do so with observable levels of resource and spatial inefficiency, disorder, and messiness. They also abound with strange departures from the rational, efficient, ideal, or perfect. In doing so, they collectively provide much of the common’s mass, diversity, colour, uniqueness, eclecticism, and interestingness [1]. Furthermore, agent mass, diversity and interestingness routinely draw a diversity of people to a single bounded place for a diversity of reasons, which is a catalyst for synergies, as well as emergent social, civic, and cultural activities.

On the other hand, shopping malls are reflective of mechanical order. They often have connectivity, which is usually privately owned and managed, and some business diversity. However, the premises are monopoly-owned and rigidly controlled by top-down shadow governments. The shopping centre specialises in offering locations to the robust, generally chain stores with a broad appeal and high turnovers. This produces an ordered system where well-known national and international chain stores offer a range of standardised products to a broad clientele [3].

Based upon the principles of complexity activity, the complex commons will have greater mass than the top-down order of shopping malls. Our research tested this hypothesis by comparing the mass of commercial activity in Singapore’s town or neighbourhood activity centres via the number and diversity of activity centres, premises, business, and activity centre-focussed jobs per 1,000 households.

The Singapore government has used state planning and land ownership to develop and expand the city via 23 new towns since 1965. Each of these new towns was planned, designed, and developed to be self-reliant. A plank of this self-reliance was the development of three levels of activity centres (town, neighbourhood, and precinct).

Prior to 1995, premises in ‘old generation’ town and neighbourhood activity centres were connected to one another by outdoor ground level open-air pedestrian malls, plazas, and/or sidewalks (Figure 1 & 2). They are also predominantly publicly owned and leased by independent businesses.

Since 1995, it has become increasingly common for town and neighbourhood activity centres to be configured partially or fully as ‘new generation’ centres. New generation centres are usually privately owned multilevel shopping malls with premises predominantly leased by chain stores and franchises (Figure 3 & 4).

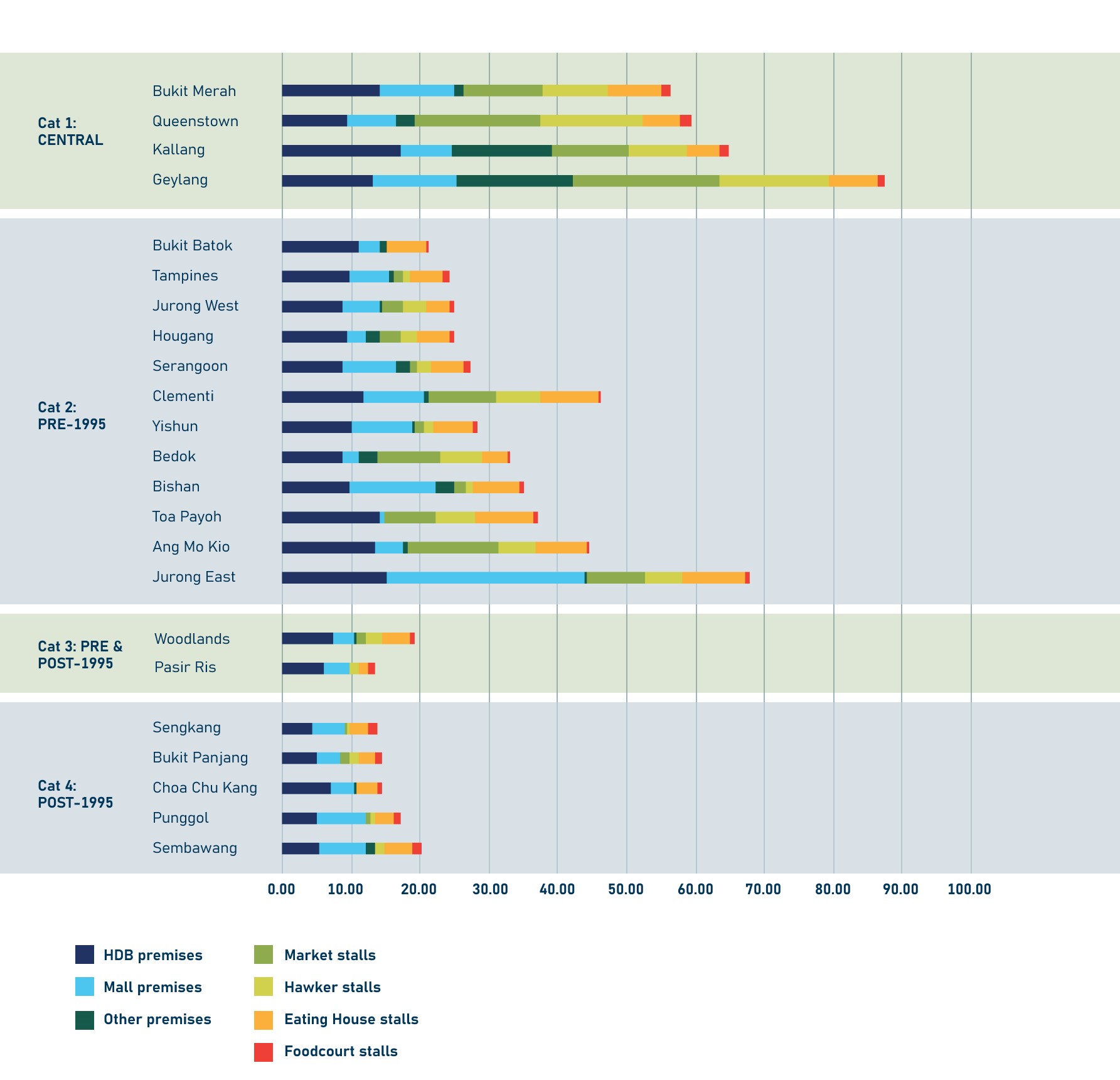

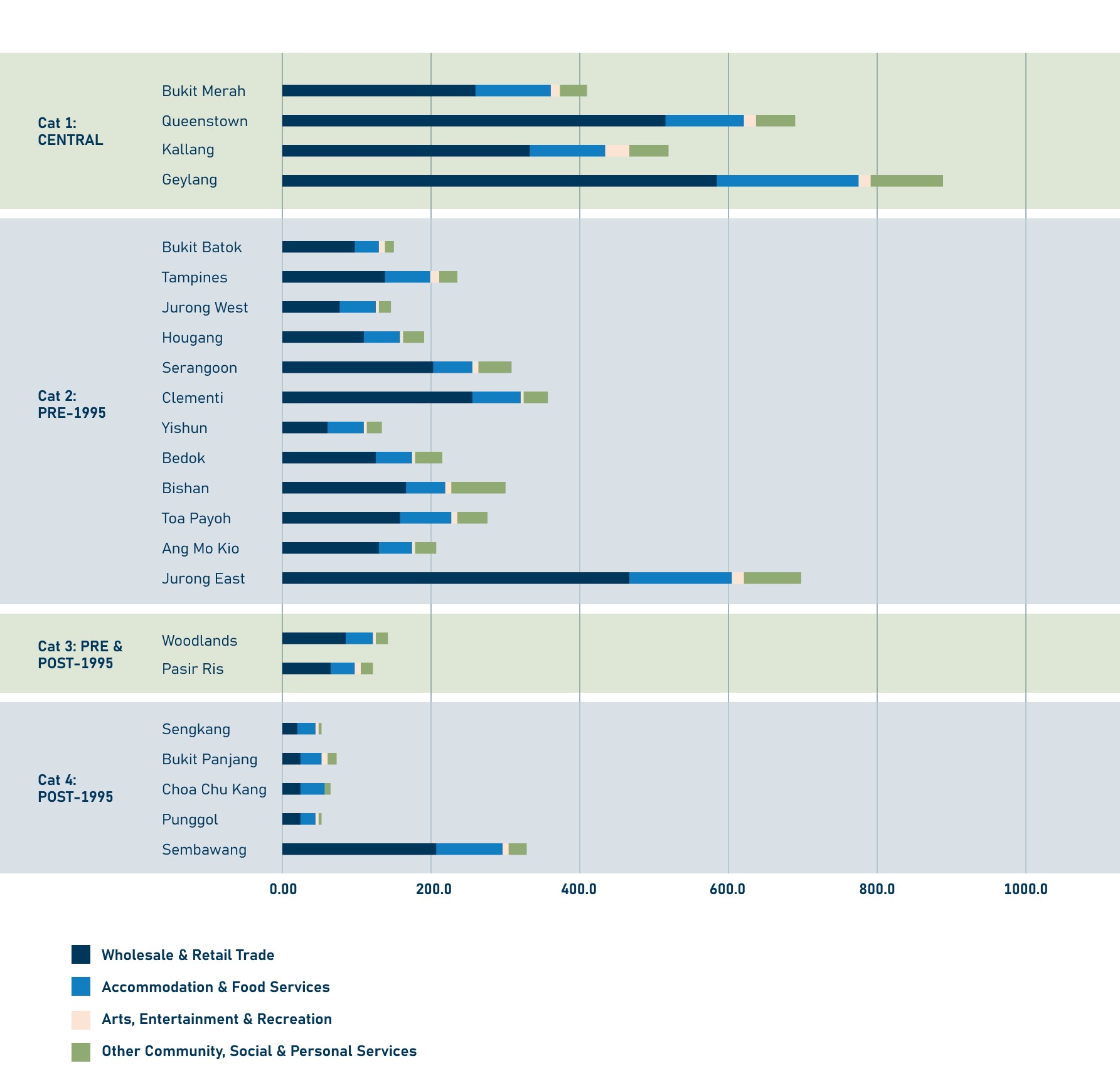

Our research has shown that the design and governance of old generation activity centres enabled them to develop and evolve as complex adaptive subsystems of the city. On the other hand, new generation malls, like malls internationally, lack the principles of complexity and are systems of top-down mechanical order. Our research shows that pre-1995 neighbourhoods with complex old generation activity centres have considerably greater mass in the form of premises (Figure 5), businesses, and employment (Figure 6) than post-1995 areas dominated by new generation activity centres.

These differences are significant. For example, Ang Mo Kio has 3.2 times as many premises per 1,000 residents as Punggol, which results in over four times as much activity centre employment. If there were similar numbers of premises in Punggol as there are in Ang Mo Kio, there would be 1,630 more businesses and 9,200 more jobs in the area.

Our research shows that design, management and ownership are important for the creation of complexity in neighbourhood activity centres. In addition, it shows that when complexity is created, it leads to greater mass and diversity in the form of businesses and employment. We assume it also leads to emergent phenomena; however, this is yet to be fully investigated.

Dr Michael McGreevy, a Research Fellow with NUS Cities, has an academic and professional background in urban planning and design. To find out more about his research into the relationship between complexity and good urban planning, please read his journal article: Complexity as the telos of postmodern planning and design

References

[1] McGreevy, M. P. (2017). Complexity as the telos of postmodern planning and design: Designing better cities from the bottom-up. Planning Theory, 17(3), 355-374. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095217711473

[2] Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity: A guided tour. Oxford university press.

[3] Mitchell, S. (2007). Big-box swindle: The true cost of mega-retailers and the fight for America's independent businesses. Beacon Press.

[4] Page, S. E. (2010). Diversity and complexity. Princeton University Press.