Like father, like son? Social engineering and intergenerational mobility in housing consumption

Unaffordability and rising inequality in housing markets, along with societal immobility, pose tensions within society, and greatly impact social cohesion. Cities are urged to address this inequality with policies aimed at providing more affordable public housing. Professors Sumit Agarwal, Yi Fan, Wenlan Qian, and Tien Foo Sing investigate the effect of large-scale public housing on the intergenerational mobility of children born to less-favoured families, using Singapore’s Build-To-Order (BTO) public housing scheme as a case study.

Dr Sumit Agarwal,

Low Tuck Kwong Distinguished Professor of Finance at the Business School and a Professor of Economics and Real Estate at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He is the Managing Director of Sustainable and Green Finance Institute at NUS. He is also the President of Asian Bureau of Finance and Economic Research.

Dr Yi Fan,

Associate Professor in NUS Business School’s Department of Real Estate, researches on issues of social and environmental sustainability

Dr Wenlan Qian,

Professor of Finance and Real Estate and Ng Teng Fong Chair Professor in Real Estate at the NUS Business School. She is fellow of the Asian Bureau of Finance and Economics Research, Luohan Academy at Alibaba Group, and the Homer Hoyt Weimer School of Advanced Studies in Real Estate and Land Economics. Currently, Wenlan Qian is editor of Real Estate Economics and associate editor of Financial Management.

Dr Sing Tien Foo,

Provost’s Chair Professor in NUS Business School’s Department of Real Estate, has researched and written extensively on housing policy and economic behaviour including the Kiasunomics series

Intergenerational inequality in the housing market

Families of lower socio-economic status often face budget constraints when raising children. These constraints significantly impact their ability to invest in their children’s human capital, ultimately affecting the social mobility of the next generation.

Such inequality is especially pronounced in large expenses, such as housing. This study incorporates ex-post housing transaction records into an intergenerational framework to analyse the transmission of material wellbeing across generations, specifically focusing on correlations in housing consumption between generations.

Singapore’s affordable housing programme to enhance mobility

The tradeoff between housing consumption and investment in children’s human capital influences intergenerational inequality in society. To mitigate this inequality, some governments offer affordable housing programmes [1] to alleviate the budget constraints of less-favoured families, enabling them to invest more in their children's human capital, and so, promote intergenerational mobility [2].

Singapore’s nationwide affordable housing scheme provides subsidies to about 80% of residents of public housing apartments built by the Housing and Development Board (HDB), a government agency that has managed the construction and maintenance of Singapore’s public housing since 1960. Proportionately more grants are offered to financially constrained families.

To test the causal impact of public housing on intergenerational mobility for families of lower socio-economic status, a difference-in-differences (DiD) quasi-natural experiment was conducted using the launch of the Build-to-Order (BTO) scheme. The BTO scheme is currently the HDB’s main allocation scheme, which was launched in 2001 to build flats based on the actual number registered for, instead of the previous method of building ahead of demand. The DiD compares changes in an outcome variable before and after the BTO scheme intervention between a treatment group and a control group [3].

The first batch of flats was constructed and completed under the BTO scheme in 2005. Through this scheme, households with a monthly income not exceeding $14,000 (USD 10,400) are eligible to purchase new public housing flats at affordable prices and with substantial subsidies [4]. The scheme addresses the housing needs of lower-income, first-time Singaporean families while helping to balance demand and supply in the public housing market. By sorting children growing up in public housing into the treatment group and those growing up in private housing into the control group, this study investigates whether, and to what extent, public housing can promote upward mobility for children born to less advantaged families.

BUILD-TO-ORDER SCHEME

Prospective home buyers apply to ballot for a unit in a HDB project at their desired location. Once demand

for the units in the project exceeds 70%, HDB begins construction and typically finishes the project in about 3 years.

This contrasts with HDB’s previous policy of building flats ahead of projected demand.

Data and methods for this study

This study uses a proprietary dataset comprising 2,171,383 Singaporean residents who were at least 20 years old between 1996 and 2018 and had a valid housing address, allowing the formation of parent-child pairs based on shared home addresses. A total of 147,560 parent-child pairs from different registered residences were identified.

This dataset was then merged with housing transaction data from the Real Estate Information System (REALIS) for private housing transactions, published by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), and with public housing transaction records from the HDB website to analyse housing consumption among parent-child pairs.

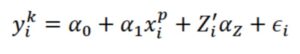

The regression model uses the housing rank of the parents in a family from the first observed wave (𝑥ip), along with Z, control variables (including the ages and squared ages of both parents and children), to predict the housing rank of the child in the same family in the last observed wave (𝑦ik). Standard errors are clustered at the family level in the model.

The hypothesis that affordable public housing alleviates the budget constraints of lower socio-economic status families, enabling them to invest more in their children’s human capital and thereby promoting intergenerational mobility for children growing up in HDB flats, was examined using a DiD regression model.

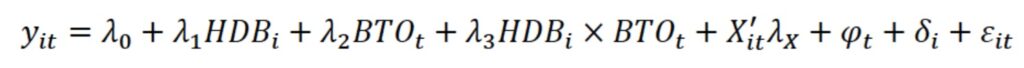

The DiD model included an interaction variable (𝐻𝐷𝐵I * 𝐵𝑇𝑂t), which combines the binary indicator of parental public housing ownership (𝐻𝐷𝐵I = 0 or 1) and a dummy variable for the cutoff year 2004 (𝐵𝑇𝑂t = 0 or 1), marking the first cohort of BTO residents who began to smoothen their consumption patterns.

The outcome variable in this model is an indicator variable, where 𝑦it = 1 if a child’s housing rank surpasses the parents' housing rank, or reflects the difference in rank between the child and the parents.

This indicator variable is measured using the parents' housing status (𝐻𝐷𝐵i = 1 if the first observed housing is public housing, and 0 otherwise), a dummy variable (𝐵𝑇𝑂t = 1 if the first observed year of the parents is 2004 or later), a demographic vector including ages and squared ages of parents and children (𝑋it), and time and regional fixed effect (𝜑t and 𝛿i respectively). Standard errors are clustered at the family level in the model.

Findings

High intergenerational mobility in housing consumption

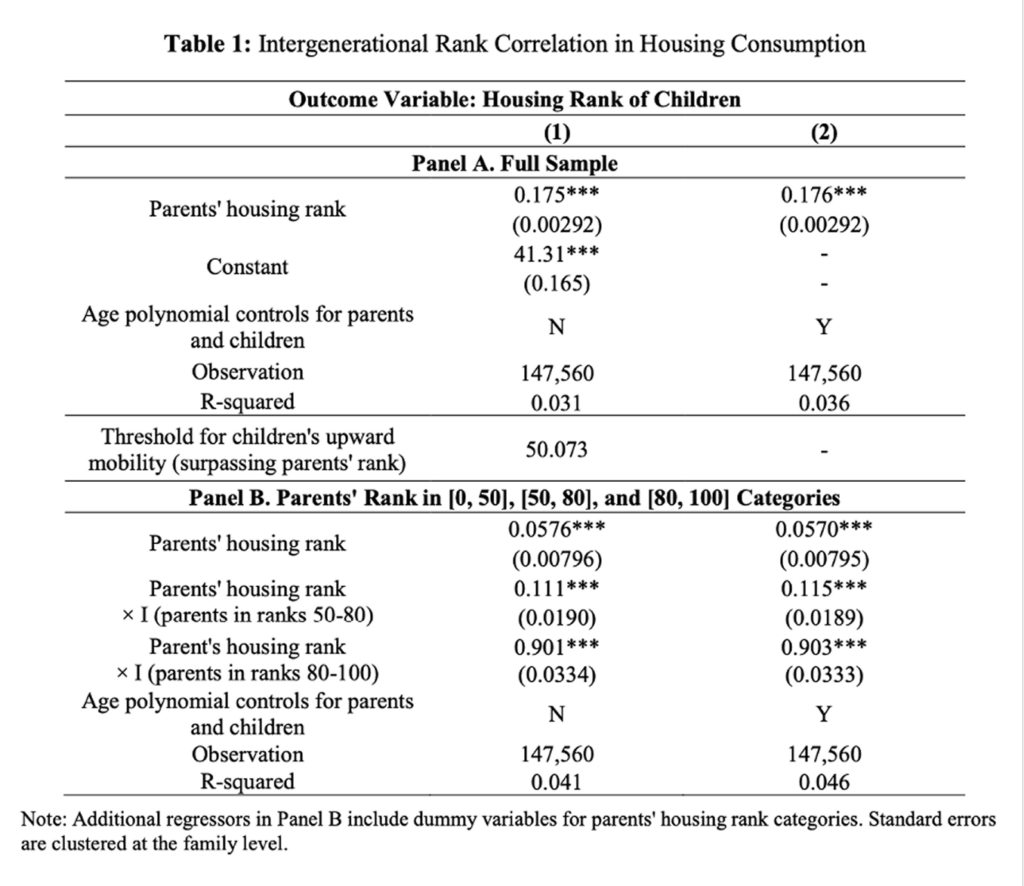

The first finding is the high mobility in average intergenerational housing consumption, with an estimate of 0.18 and statistical significance at the 1% level in columns (1) and (2) of Table 1. Columns (1) and (2) report the results without, and with, the age controls for children and parents, respectively. If the parents’ housing rank increases by 10 percentile ranks, their child’s housing rank will rise by 1.8 percentile ranks.

This finding is aligned with Yip's (2019) study [6], which used a smaller sample of 40,000 father-son pairs in Singapore, as well as the study conducted in the United States that adopted home ownership rates from the data [7] from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), the longest running longitudinal household survey in the world, that started in 1968 in the US.

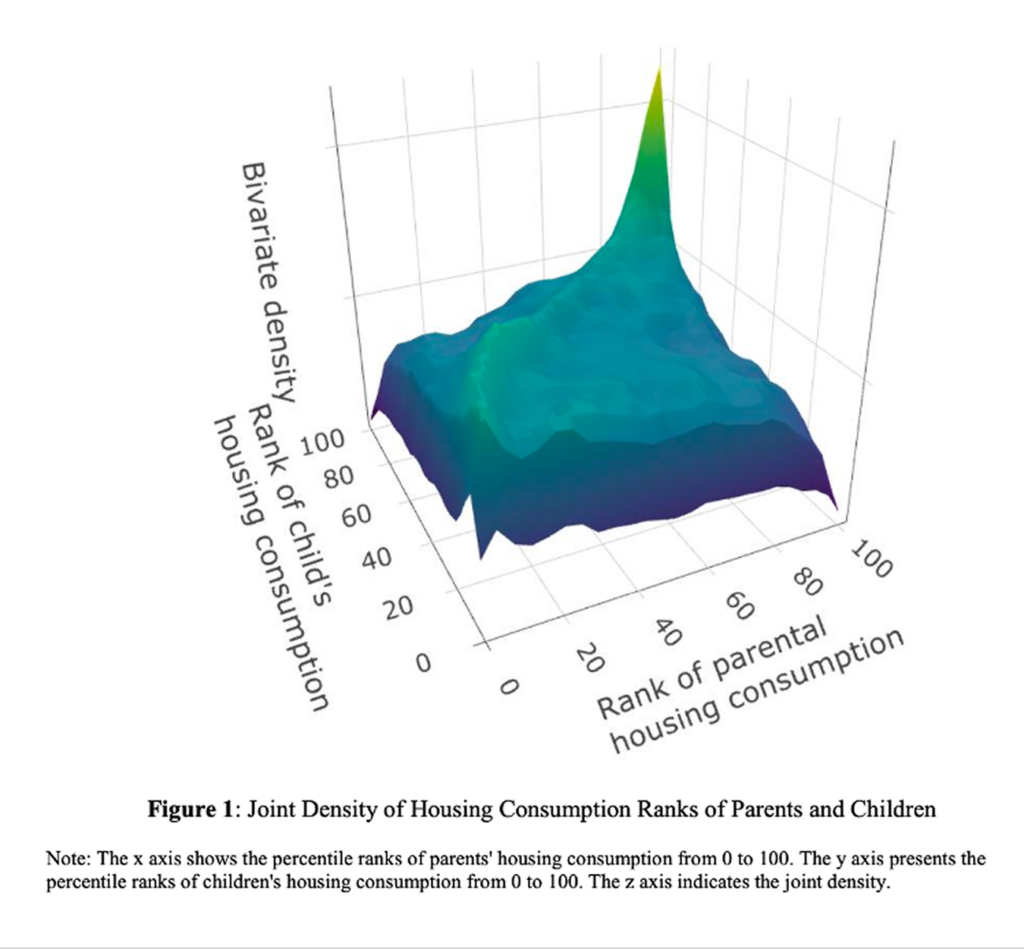

Using housing prices as proxy for the amount of housing consumption, this study contributes to the literature on the average correlation in housing consumption across generations. The visual patterns of joint density distributions of housing consumption ranks of parents and children are presented in Figure 1.

The x, y, and z axes represent the percentile ranks of parents, children, and their joint densities, respectively. It shows that the closer the children's ranks are relative to their parents' ranks, the higher the joint probabilities, as captured by the ridge in the 3D graph.

Notably, the joint densities reach the pinnacle for the richest families, indicating the highest degree of housing persistence across generations, with children maintaining similar housing standards or types as their parents.

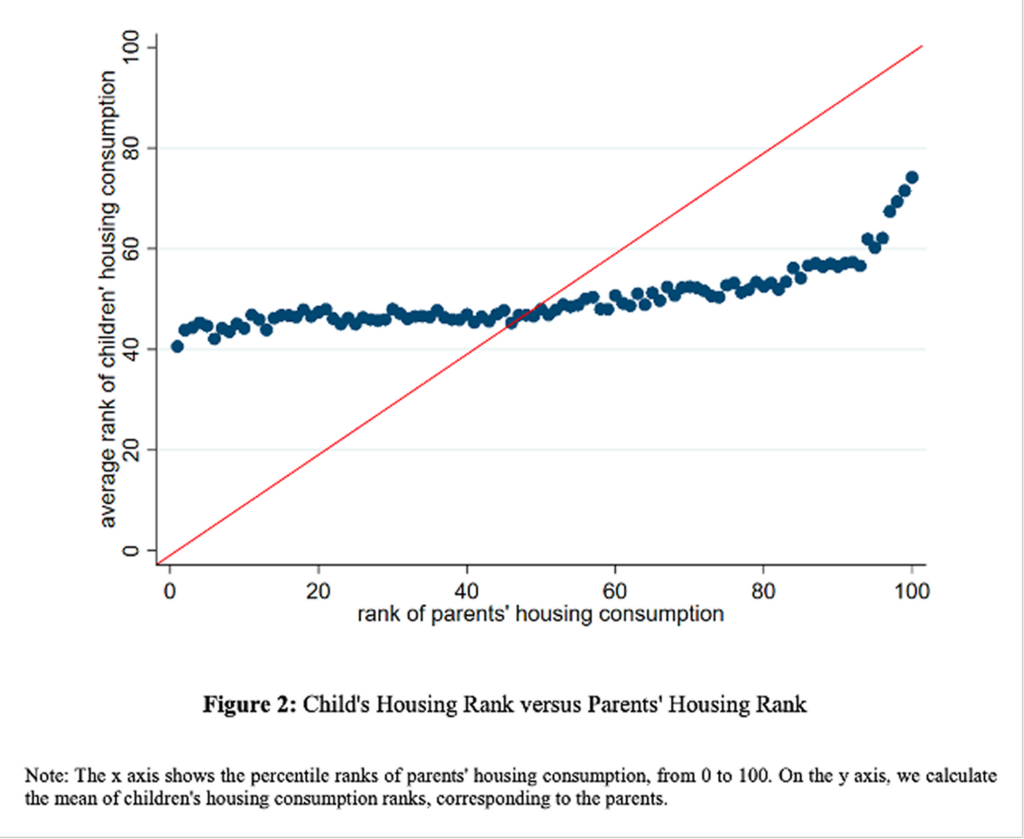

The 2D projection of the ridge observed in Figure 1 is presented in Figure 2, to capture the non-linear pattern of the average housing rank of children (y-axis) and the corresponding rank of their parents (x-axis).

The 45-degree line indicates that children maintain the same housing rank as their parents, reflecting the concept of no absolute mobility. The threshold point 𝑦*, at which the plotted line intersects with the 45-degree line, is at the 50.07 percentile rank.

An upward mobility in housing consumption for children born to parents in the bottom half of the housing consumption ranks can be observed from the non-linear plot pattern. Children from less well-off families often experience significant improvement, showing an upward trend in housing consumption compared to that of their parents.

The regression of intergenerational ranks, as presented in Panel B of Table 1, was conditioned on parents’ housing ranks (the bottom (0-50 ranks), middle (50-80 ranks), and upper (80-100 ranks) status) to examine intergenerational mobility in housing consumption among families of various socio-economic statuses.

This empirical finding aligns well with the graphical evidence in Figure 2. While children who grew up in public housing experience an upward shift in their housing consumption relative to their parents, those born to families with parents in the upper end of housing ranks, primarily in private housing, tend to maintain their housing status.

Positive impact of public housing on intergenerational mobility

This study continues to examine the drivers of substantial upward mobility in housing consumption observed among children born to families with parents in the lower housing ranks.

A statistically significant negative correlation of -0.2 was found in the graph plotting the intergenerational rank-rank coefficient (y-axis) against the percentage share of public housing for 156 subzones in Singapore (Figure 3).

The results indicate that a higher share of public housing in a subzone is associated with a lower intergenerational rank correlation, suggesting a negative (or positive) relationship between the share of public housing and intergenerational persistence (or mobility).

What explains the higher intergenerational mobility observed among children who grew up in public housing? The Difference-in-Differences (DiD) estimation, which plots the probabilities of children surpassing their parents in housing rank between the treatment and control groups over time, suggests that this high intergenerational mobility may be driven by the affordable public housing scheme.

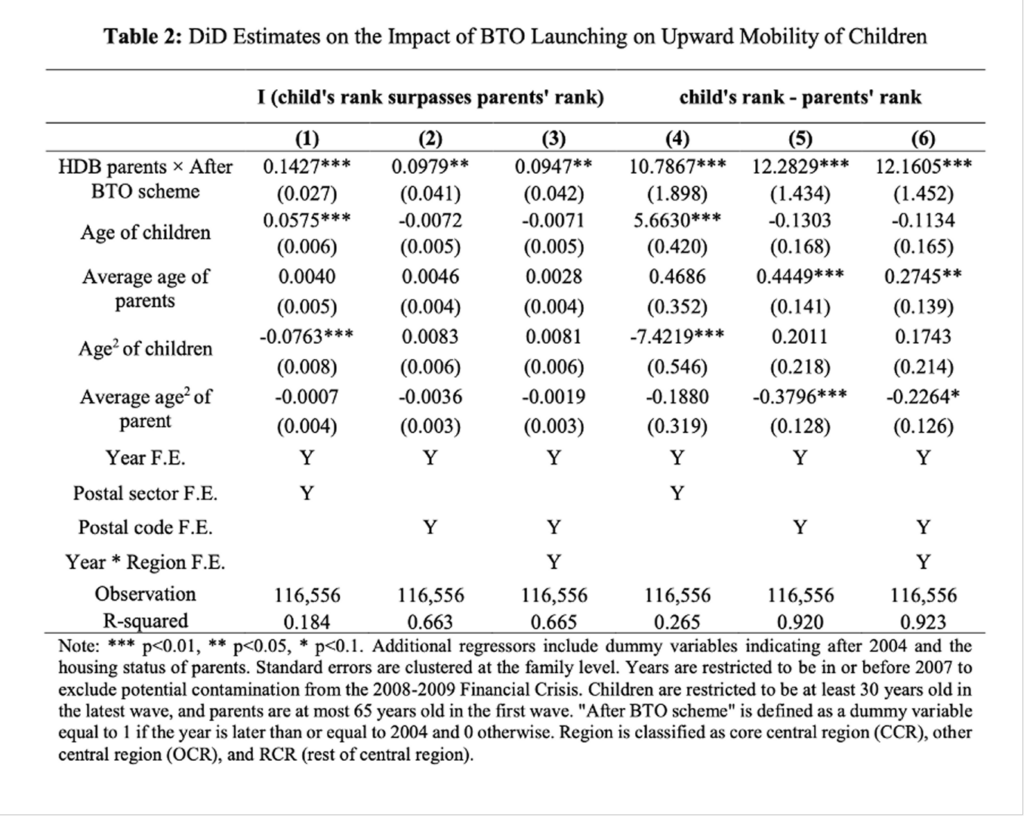

Table 2 shows the DiD estimates, using the cutoff year of 2004 to align with the first cohort of BTO (Build-To-Order) residents.

Columns (1) to (3) present the results using the indicator variable for children surpassing their parents in housing rank as the outcome variable, while Columns (4) to (6) provide the results using an alternative measure of rank difference.

The analysis finds that children who grow up in affordable public housing are 9.5% more likely to surpass their parents in housing rank compared to their peers raised in private housing (Column (3)). This estimate is statistically significant at the 1% level. The DiD in Column (6) with the building-level fixed effects and unobserved time-varying factors shows a statistically significant estimate of 12.2.

Policy implications

In conclusion, this study uses the introduction of the BTO scheme as an exogenous policy shock to demonstrate that affordable public housing significantly enhances upward mobility across generations.

Children who grew up in public housing estates exhibit a 9.5% higher likelihood of surpassing their parents in the housing consumption ranks, which translates into an increase of 12 ranks in magnitude.

While this study is grounded in the context of Singapore, the implications of affordable housing policy are relevant for other countries aiming to promote upward mobility, particularly for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Through a nation-wide analysis of public housing policy, the findings reveal that affordable public housing provides a new, more stable and equitable approach to promoting intergenerational mobility in cities on a broad scale.

References

[1] Chetty, R., Hendren, N., and Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 33 106(4):855–902.

[2] Mogstad, M. (2017). The human capital approach to intergenerational mobility. Journal of Political 36 Economy, 125(6):1862–1868.

[2] Fagereng, A., Mogstad, M., and Ronning, M. (2021). Why do wealthy parents have wealthy children? Journal of Political Economy, 129(3):703-756.

[2] Li, M., Goetz, S. J., and Weber, B. (2018). Human capital and intergenerational mobility in U.S. counties. Economic Development Quarterly, 32(1):18–28.

[2] Smith, M., Yagan, D., Zidar, O., and Zwick, E. (2019). Capitalists in the twenty-first century. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(4):1675–1745.

[2] Hu, Y. & Qian, Y. Gender, education expansion and intergenerational educational mobility around the world. Nature Human Behaviour 7, 583–595 (2023).

[2] Biasi, B. (2023). School finance equalization increases intergenerational mobility. Journal of Labor 32 Economics 41 (1):1-38.

[3] ScienceDirect. (2024). Difference in differences—An overview | sciencedirect topics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/difference-in-differences

[4] HDB. (2024, July 4). Hdb | keeping bto flats affordable. https://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/about-us/news-and-publications/publications/hdbspeaks/Keeping-BTO-Flats-Affordable

[5] Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, and Emmanuel Saez. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129 (4):1553-1623.

[5] Chetty, R. and Hendren, N. (2018a). The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I:Childhood exposure effects. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3):1107–1162.

[5] Chetty, R. and Hendren, N. (2018b). The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility II:County-level estimates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3):1163–1228.

[6] Yip, Chun Seng (September 3, 2019). Intergenerational Income Mobility in Singapore. Singapore, Ministry of Finance.

[7] Waldkirch, A., Ng, S., and Cox, D. (2004). Intergenerational linkages in consumption behavior. Journal of Human Resources, 39(2):355–381.