Longer commutes and mental health risks

At a time when mental health concerns have increasingly been raised in the public consciousness, it is important that connections between key facets of different urban systems and their impacts on mental health are examined and elucidated. Dr Wang Xize explores the potential mental health risks from longer journey-to-work times, using Beijing as a case study.

Dr Wang Xize,

NUS Department of Real Estate

Rising mental health concerns

In an era marked by increasing interconnectedness and technological advancement, the systems that underpin societies — from transportation and energy grids to healthcare and financial markets — are becoming increasingly complex. This complexity poses significant challenges for policymakers, as traditional, linear approaches to governance often fall short in addressing the dynamic and unpredictable nature of these systems. Besides traditionally accepted medical factors, mental health can also be shaped — and thus improved— by urban environmental factors. Using survey data in Beijing, China, this study focuses on a specific urban environmental factor: the journey to work and examines its relationship with depressive symptoms. Investigating the commute-depression relationship can provide insights for policymakers and private-sector managers to develop strategies that can help enhance mental health conditions.

Connecting the commute with depression

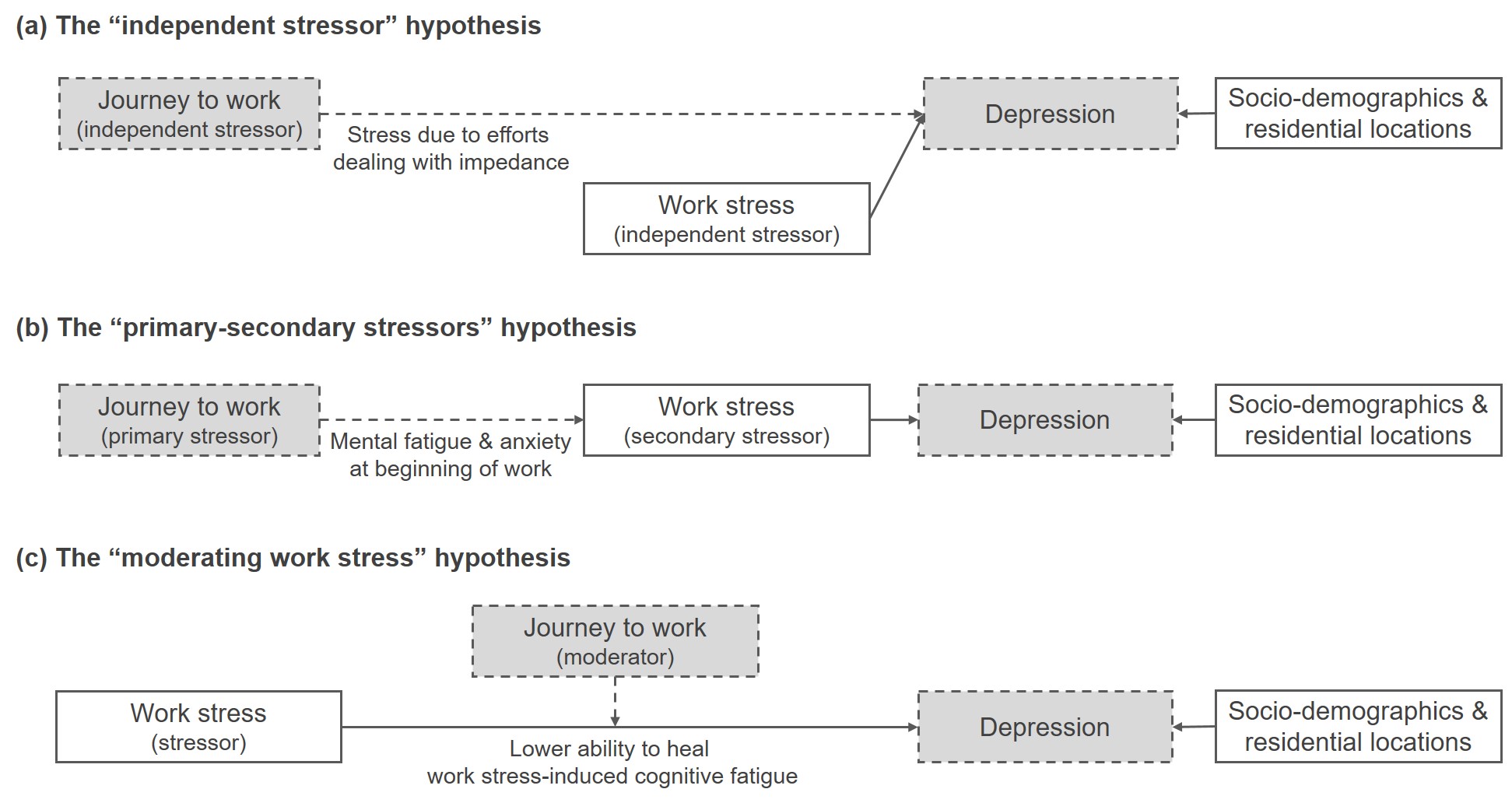

The connection between commuting time and mental health can be theoretically explained through the impedance theory and the stress process theory. According to the impedance theory, commute trips act as psychological hurdles, or “impedances,” that create stress; when people experience stress, their levels of cortisol increase, and those who constantly have high cortisol levels are more likely to have depression and other mental health problems [4]. The stress process theory further explains how long commutes can increase the risk of depression by acting as direct stressors or triggering secondary stressors [5]. For instance, a long commute time may increase individuals’ mental fatigue, anxiety, and feelings of time pressure at the beginning of a workday, thus increasing their work stress level. Subsequently, the increased work stress level is further associated with a higher likelihood of depression [6].

Additionally, the stress process theory introduces “psychological resources,” which are non-physiological factors that help individuals cope with stress [5]. For example, certain urban environment factors such as a shorter commute time can give an individual a higher ability to heal from work stress-induced cognitive fatigues; therefore, this individual may have relatively weaker work stress-depression associations [7]. Based on these theories, there are three possible channels linking commute time to depression: direct stressor, indirect stressor, and moderator (Figure 1).

Data and methods for this study

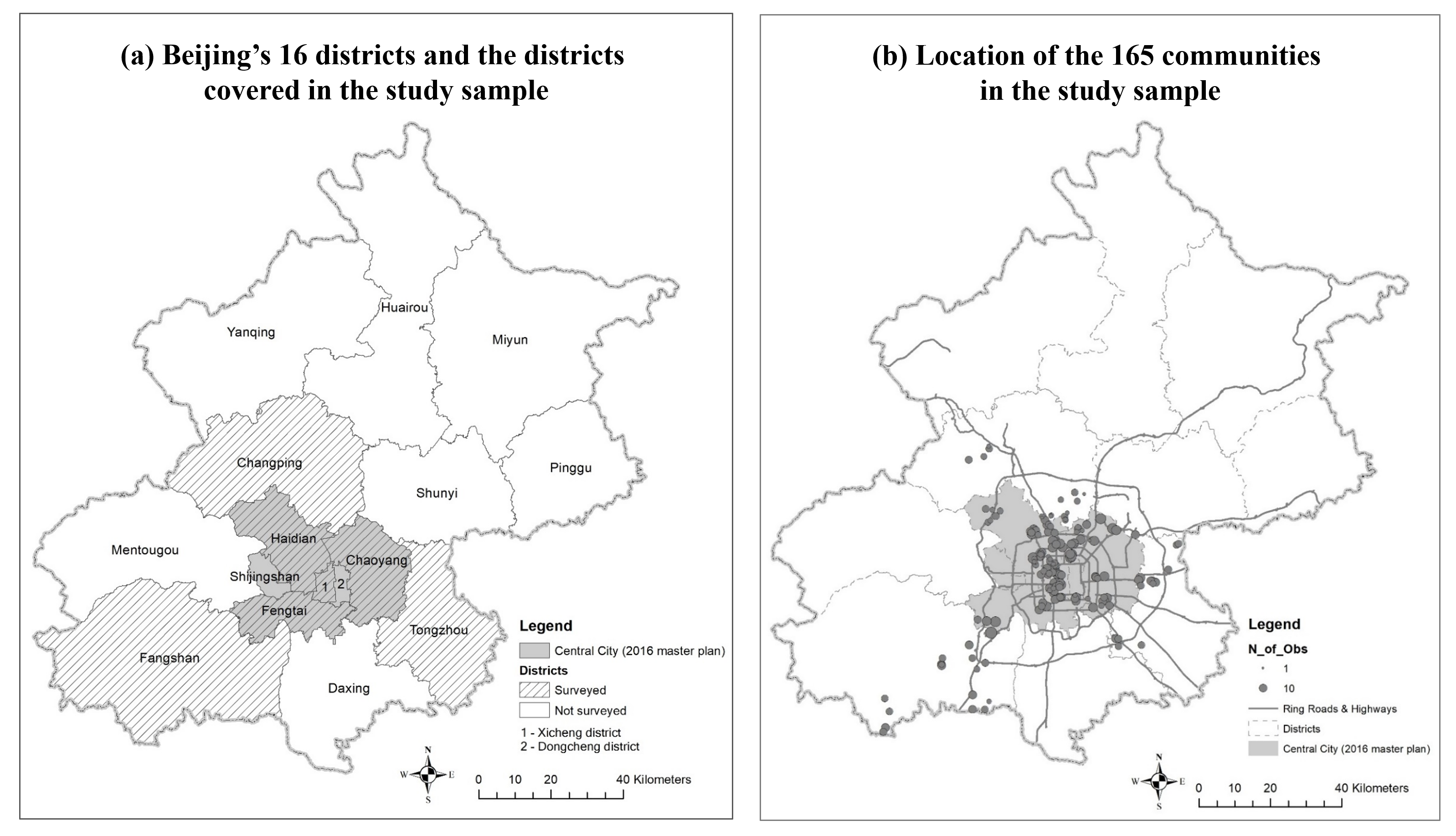

This study uses Beijing, China, as a case study and examines the associations between door-to-door commute time and depressive symptoms for 1,528 survey respondents in urban and suburban neighborhoods. The dataset for this study comes from a survey conducted in Beijing, China, between November 2018 and April 2019, covering seven of Beijing’s 16 districts (Figure 2).

To test the three hypotheses regarding commute time, work stress, and depression, the study proposes regression models to analyze these relationships. Specifically, the outcome variable (i.e., the variable being predicted or explained) is whether an individual screens positive for depression based on the CESD-10 depression scale [8], and the key exposure variable (i.e., the main variable influencing or predicting the outcome variable) measures the individual's door-to-door commute time from home to workplace on a normal day. The regression model also includes levels of work stress, as well as sociodemographic control variables (i.e., variables included to ensure that within the model there is minimal influence of other factors on both the key exposure variable and the outcome variable), along with a binary (i.e., yes/no) indicator of whether the individual lives in the central city.

Findings

Commute time, depression and work stress

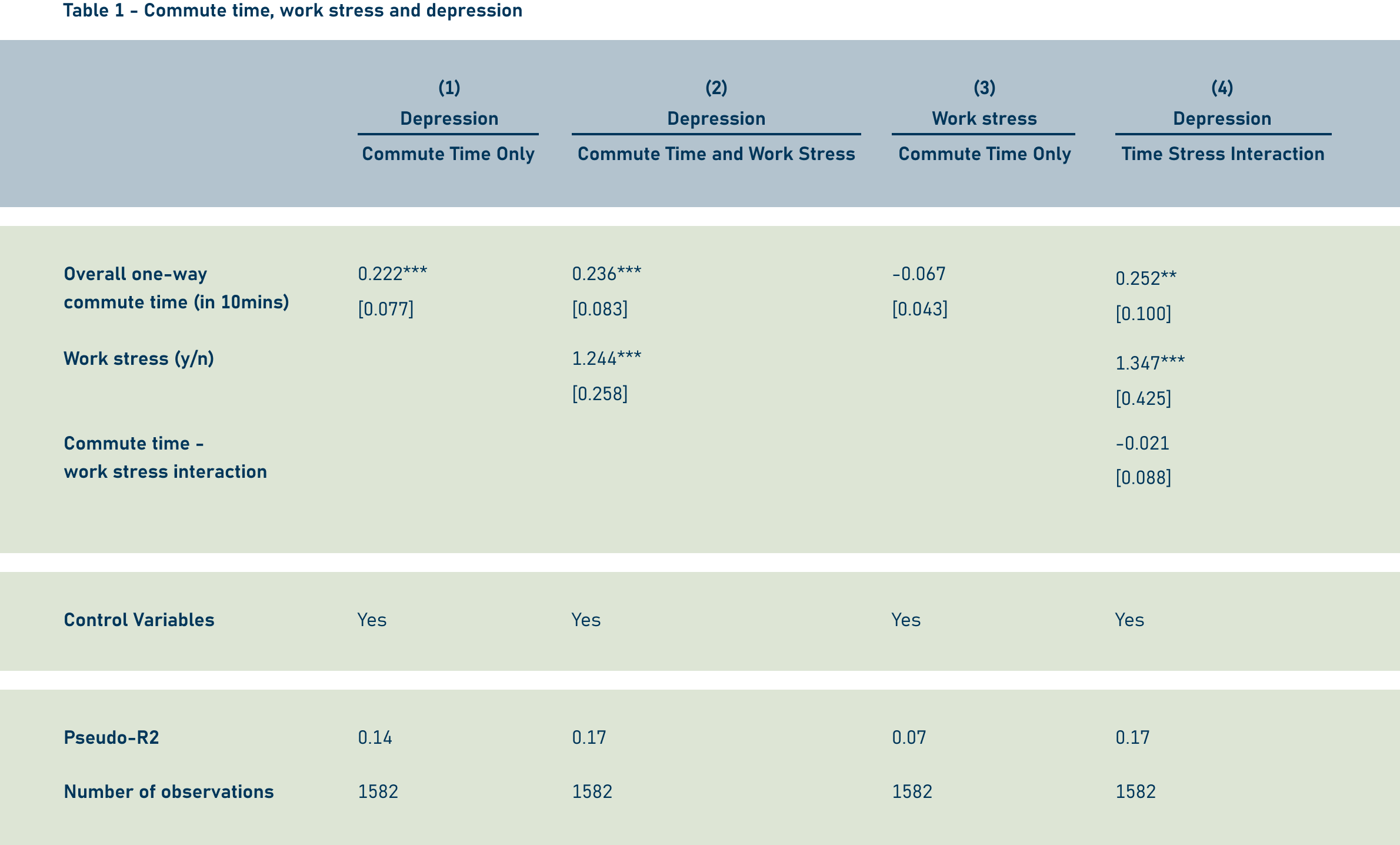

First, longer commute times are associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms (Table 1). Holding other factors constant at their means (for continuous variables) or modes (for categorical variables), every additional 10 minutes of commute time increases the likelihood of depression by 1.1%, and individuals with high work stress are 3.7% more likely to experience depression compared to those with low or no work stress.

Applying Sobel’s test to the coefficients of Models 1–3 in Table 1, the commute-depression association is not triggered by higher work stress. Furthermore, the interaction term between commute time and work stress is not statistically significant, indicating that commute time does not serve as a moderator of the work stress-depression associations.

These findings align with previous studies conducted in various urban and cultural settings, reinforcing the positive association between longer commute times and depressive symptoms [9] [10]. These results also contribute to the theoretical and empirical literature linking travel behaviour and stress, further establishing the significant impact of longer commutes on mental health [4] [11].

Mode-specific effects: Highest for motorcyclists, lowest for non-motorized modes

Second, in terms of mode-specific time, time spent in transit, private automobiles, and mopeds/motorcycles is significantly associated with depression, whereas time spent in non-motorized modes is not significantly associated with depression (Table 2). On average, every additional 10 minutes spent in transit, private automobiles, and mopeds/motorcycles is associated with a 1.1%, 1.3%, and 1.9% higher likelihood of depression, respectively.

The marginal effect of time spent on mopeds/motorcycles is the highest among the five mode-specific time variables, almost twice the size of the average effects shown in the previous section. There were no significant effects of traffic delay time or multimodal commuting. This finding implies that riding mopeds/motorcycles is a strong contributor to mental health issues. In Beijing (and most other Chinese cities), there are no dedicated motorcycle lanes; moped and motorcycle users can use both the automobile and bicycle lanes (Figure 3). Hence, a possible explanation of this finding is that driving mopeds takes relatively higher mental effort than other modes due to the mopeds’ ability to cut through vehicles and bicycles on congested roads. Additionally, driving mopeds may generate higher stress levels due to mopeds’ relatively higher risk of traffic crashes. This situation may also explain the slightly higher marginal effect for time in a car than time in transit since driving takes more mental effort than taking trains and buses.

There were no significant associations between time spent in non-motorized modes and depression. Such findings are consistent with previous studies [12]. The insignificance of active travel time is likely to be a composite effect of two different forces. On the one hand, a longer time spent on the journey to work is associated with a higher likelihood of depression, but, on the other hand, a longer time being physically active is associated with a lower likelihood of depression [13]. Although the net effect is ambiguous, the insignificance of this variable may be an outcome of these two counteracting effects cancelling out each other. The insignificance of walking/biking time implies that an active mode of work may promote, or at least will not harm, one’s mental health.

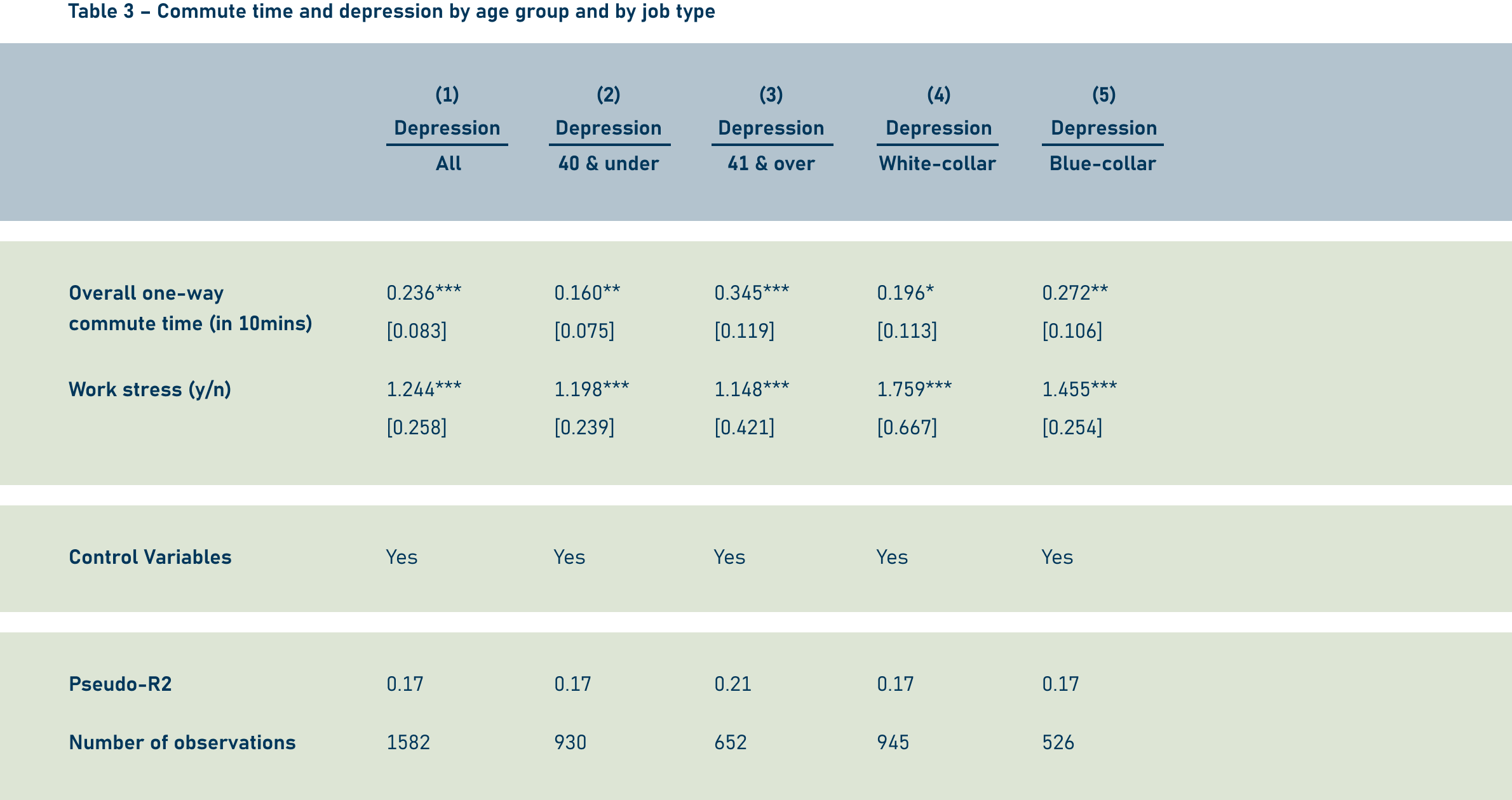

Subsample analysis: Vulnerability for older commuters and blue-collar workers

Third, our subsample models identify two subgroups that are more sensitive to commuting as a contributor to depression (Table 3). The first subgroup comprises individuals in their 40s or older. One potential explanation is that, as people age, they are more prone to fatigue related to commuting or other activities [14]. Another possible explanation is that people of different generations may have different attitudes towards travel and have different expectations of the ideal commute time and modes [15].

The second subgroup includes blue-collar workers, who are more likely to use fatigue-inducing modes of transport. For instance, in this study sample, 18% of the blue-collar workers reported using mopeds or motorcycles in their commute, compared to only 10% among white-collar workers. Another possible explanation is that blue-collar workers have a more fixed work schedule than white-collar workers, and as a result, their commuting experience is less likely to be by choice than that of white-collar workers [16].

Policy implications

The findings of this study support and highlight the importance of urban and transportation planning in promoting the mental health of urban residents. Efforts to reduce commute time and optimize transportation network performance will help promote the mental health of residents. For instance, a flexible work schedule and working at home one day a week should reduce the average commute time per day, decreasing the probability of depression.

Policies and programmes to reduce the use of private automobiles and motorcycles and promote the use of non-motorized modes and transit would also benefit people’s mental health. Planners and policymakers should pay special attention to those using mopeds or motorcycles in their commute, as they seem to be the most vulnerable group for converting long commute time to mental health issues. In addition to traffic safety programmes for moped or motorcycle users, policymakers and planners should consider providing dedicated lanes for the different users.

In addition, policymakers should pay attention to blue-collar workers and those with relatively higher ages, as these workers are relatively more vulnerable to long commute times, contributing to depression. Among the many other policy suggestions mentioned, programmes to improve the job-housing balance for older blue-collar workers deserve attention.

For instance, the Beijing Municipal Government has started a joint-ownership public housing programme (“Gong you chan quan zhu fang”), which offers lower prices but has strong regulations on eligibility to purchase and permission to transfer. Such joint-ownership estates are usually located at the fringe of central city areas, have good access to the rail transit system, and have amenities precisely fit for the lower middle-class lifestyle. Hence, such a housing programme would be beneficial for older and blue-collar workers to live in a place that has reasonable transit access and, among other benefits, reduces the mental health risks of their journey to work.

More about this study

For more details of the methods, findings, and discussion, please refer to the full paper (open access) via: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103316.

References

[1] Subramaniam, M., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., Shafie, S., Chua, B. Y., Sambasivam, R., ... & Chong, S. A. (2020). Tracking the mental health of a nation: prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in the second Singapore mental health study. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences, 29, e29.

[2] Huang, Y., Wang, Y. U., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Yu, X., Yan, J., ... & Wu, Y. (2019). Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(3), 211-224.

[3] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, (2012). Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[4] Novaco, R. W., Stokols, D., & Milanesi, L. (1990). Objective and subjective dimensions of travel impedance as determinants of commuting stress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(2), 231-257.

[5] Pearlin, L. I., & Bierman, A. (2013). Current issues and future directions in research into the stress process. Handbook of the sociology of mental health, 325-340.

[6] Ganster, D. C., & Rosen, C. C. (2013). Work stress and employee health: A multidisciplinary review. Journal of management, 39(5), 1085-1122.

[7] Evans, G. W. (2003). The built environment and mental health. Journal of urban health, 80, 536-555.

[8] Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, 77-84.

[9] Feng, Z., & Boyle, P. (2014). Do long journeys to work have adverse effects on mental health? Environment and Behavior, 46(5), 609-625.

[10] Wang, X., Rodríguez, D. A., Sarmiento, O. L., & Guaje, O. (2019). Commute patterns and depression: Evidence from eleven Latin American cities. Journal of Transport & Health, 14, 100607.

[11] Avila-Palencia, I., De Nazelle, A., Cole-Hunter, T., Donaire-Gonzalez, D., Jerrett, M., Rodriguez, D. A., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2017). The relationship between bicycle commuting and perceived stress: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 7(6), e013542.

[12] Humphreys, D. K., Goodman, A., & Ogilvie, D. (2013). Associations between active commuting and physical and mental wellbeing. Preventive medicine, 57(2), 135-139.

[13] Hong, X., Li, J., Xu, F., Tse, L. A., Liang, Y., Wang, Z., ... & Griffiths, S. (2009). Physical activity inversely associated with the presence of depression among urban adolescents in regional China. BMC public health, 9, 1-9.

[14] Arnau, S., Möckel, T., Rinkenauer, G., & Wascher, E. (2017). The interconnection of mental fatigue and aging: An EEG study. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 117, 17-25.

[15] Wang, X. (2019). Has the relationship between urban and suburban automobile travel changed across generations? Comparing Millennials and Generation Xers in the United States. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 129, 107-122.

[16] Dėdelė, A., Miškinytė, A., Andrušaitytė, S., & Bartkutė, Ž. (2019). Perceived stress among different occupational groups and the interaction with sedentary behaviour. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(23), 4595