Singapore as a blue-and-green role model

In this interview, Professor Herbert Dreiseitl, Founder and CEO of DRESEITL Consulting and one of the pioneers of PUB’s “Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters” approach, explains why he is passionate about making blue-and-green an integral part of the future of cities, and how Singapore can be a role model for other cities.

Professor Herbert Dreiseitl is the Founder and CEO of DREISEITLConsulting. He was previously the Director of Ramboll, and Founder and CEO of Atelier Dreiseitl. He was instrumental in the creation of PUB’s “Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters” Guidelines, and the re-design of Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park.

Q: You have been closely involved in Singapore’s “Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters” programme, having a key role in the design of the flagship Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park and in the creation of the ABC Waters guidelines. Reflecting on your projects in Singapore, and given your experience in other cities such as Berlin, Portland, London and New York City, in what ways is Singapore unique among cities in supporting the creation of blue-green infrastructure? In what ways can Singapore learn from other cities in this area?

A: I think the building of blue-and-green infrastructure, whether it’s called “ABC Waters”, or “Sponge Cities”, or by other names, is something worldwide which is growing, and it is growing because of the urgent need to tackle climate change. I think cities around the world are now much more aware that we have to prepare our cities to be more resilient, to be more flexible, to be more ready for the extremes, to balance the extremes, and to deal with a future of extreme storms.

Climate change means that, sometimes, there will be a lot of water which suddenly comes down, and that, at other times, we have long weeks of drought, with no water at all. As we face hotter temperatures and poor air quality, flora and fauna are suffering from that. Trees are dying, and so on. I think that's a big trend we can see. And this is actually happening in almost all climate zones: there is no part of the Earth which is excluded from that.

Singapore specifically has a very critical part to play in addressing this. I think Singapore is in a way also unique, because Singapore has no hinterland. Singapore is an island. It's a city on a very small terrain. Singapore is immediately affected if there is a drought, or if there's too much water, facing an amazing amount of flooding.

I think Singapore was one of the cities in South East Asia that actually started very early on to use hard engineering, which was mostly brought in from Europe. Basically, the idea was to use canals to get rid of water as quickly as you can. Founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s vision to change this system, and to bring up, for example, the condition of the Singapore River to something which is a river where you can actually enjoy water, where you can see fish, where you can swim, was, in the early days, something which was not at all possible to imagine.

And I think, in one way, the situation in Singapore is similar to that of a lot of cities in the world, but also, it is very, very specific to its own context. Singapore, I would say, could be a role model for many other cities. In fact, it is already a flagship for many cities around the world.

I would say the big difference, when I look at Singapore alongside many cities around the world in my experience, is this: lots of cities around the world actually started to come up with “sponge city” projects before Singapore. There were water-sensitive solutions in cities like Vienna, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Portland and Berlin.

These were cities that actually already started before 2000 to come up with good concepts. But, for them, probably the need was not so urgent as it is for Singapore, as Singapore depends on water security. Singapore depends on having enough water, and, as we know, Singapore has the national policy of the Four National Taps and one of them is, of course, rainwater. I think Singapore started already with a recognition that keeping as much rainwater as possible is of utmost importance – especially when the city does not have a hinterland.

This made Singapore take extra care of the structure of urban land, and to use the city itself as a catchment. I think that is unique. Other cities like Berlin, London, New York, all have a hinterland. They basically take the water from somewhere else, bring it into the city, use it, and then discharge used water along with waste. So, they rely more on sewage treatment.

Singapore, on the other hand, has to come up with more sustainable solutions, and I think I was fascinated by this on my first visit in Singapore, which was, I think, 2006. It was around the time when the Public Utilities Board (PUB) started to think about expanding catchment areas.

That was basically how the “ABC Waters” programme began. I was in Singapore to help PUB to think about the more philosophical questions, beyond the technical engineering issues, moving into strategic thinking. What needs to be done if we say the city is the catchment for rainwater, or for harvesting water?

The first thing , of course, is managing the city structure on the surface. And that means you have to actually work in the public realm, on a lot on public properties, which are the streets, rooftops, pocket parks, parkways, greenways and the river corridors. But we have to look at the entire catchment next.

And that was basically why I think the term “ABC (Active, Beautiful, Clean)” came up. For Singapore, this is a very unique way of framing the issue, because in most cities, they would start with ‘Clean’ first, and only after this is achieved, would they say that it has to be made beautiful.

And then, finally, they start thinking about how it can be nice for people. But for Singapore, it was the other way around, it was saying: Active, Beautiful, Clean.

It has to be more than just only addressing water, catchment and water safety. It has also to be functional for making the city more liveable, making the city more beautiful.

When you do this right, you can also collect water, and you can make it clean. So, I think the programme of the “ABC Water” Guidelines was really a very, very interesting idea from Singapore, and I think, all around the world, people were very, very much aware of what Singapore was doing.

Maybe to reflect a little bit more on the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park project I did in Singapore: It was the outcome of the thinking that we needed to have a pilot project, a trendsetter for the “ABC Waters” programme. I think, at that time, I thought that Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, high up on the Kallang River, just below the reservoirs, would be a perfect spot for this.

There, you have very dense city development on both sides of a green space which had the potential to be transformed. It was a project which had a lot of potential, where Singapore was looking not just at engineering, but also at the culture – how to implement a water programme that is sensitive to local behaviour and the culture of the people living and playing at the site.

In fact, to get a better sense of this, we had a whole week working at Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park. We were actually working in a little red shed at the park, and we had no air-conditioning! We made sketches and drawings, and we went out when rain started to pour. We were so fascinated to observe how water fell and moved in the park – how little foot passes were inaccessible when the rains came. We also saw how people reacted to the downpour.

We wanted to come up with a design for how to combine good water solutions with additional services to society. By the end of that week of observation, we came up with a strategic plan which pretty much looks like how it was executed, and what you can see today.

I think Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park is also a good model because it brought different government agencies and disciplines together. During the final presentation of our proposal, we brought NParks (National Parks Board), HDB and URA (Urban Redevelopment Authority) together. We had to explain how to make an impact with “ABC Waters”, different disciplines needed to be combined.

Different approaches and solutions needed to be combined too. You have to upgrade the park. You have to change the Kallang River. You have to bring about a seamless transition between water and greenery. You also have to think about how the park is linked to walkways, to streets, and to the larger city, and the entire city design. This is a key message that’s still not fully understood in many cities. I think, even today, we have problems, because we often think we can have a quick fix. We do something to make the canal wider or higher, or so on. We don't see how the water system and the blue-green infrastructure really is influencing the entire city design and the social behaviour of people.

Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park was also a big learning experience because we could also see how to incorporate people into the design. We saw how people used the park differently. We saw how people actually did react to risky situations, like what happens when water comes up after a big storm.

Are people intelligent enough to deal with that risk? Could we work with the intelligence of people to build their awareness so they become responsible for their own safety? Do we need fences on both sides, or can we leave it open? There were actually quite a lot of very interesting discussions to the end, just two weeks before the opening. Still, at that time, there were people who were saying, we need to make two fences on both sides, because it's too dangerous. Today, I think, it’s very clear that we don't need that, and that it works very well.

But it was an experiment. There were a lot of discussions. We also had to bring in new technologies which were not used before. We brought in bioengineering techniques. We had to test out things. So, all that was actually a unique experience in the first attempt to bring blue-green infrastructure into Singapore. And I would say, in that way, Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park was really a starting flagship project that can be copied in many other cities, also in other Asian countries. In Jakarta, and in many other places, it is already starting to be copied and done, which is very, very good. But I think much more could be done.

I think what cities can learn, or Singapore can learn, is especially when I look at European cities, where, often, there is a change process that is too slow, too bureaucratic. Singapore is a small city. The city and the state are almost one. In this way, Singapore can enact change much faster than a European city can. But I think Singapore could have even more courage.

Singapore is fast, but it could be even faster. It would be good to have less bureaucratic processes and more trusting of a kind of planning culture where mindsets are already shaped by things like the “ABC Waters” guidelines, and thinking in these terms for planning becomes more natural, more instinctive. Having this kind of ingrained culture in society —this is the only way we can prepare for the future.

It should be getting normal to think in a way that is conscious about water and green so that we don't rely too much on rules. The danger is that “ABC Waters” is seen as design and planning rules for canals. But what we forget is that from the beginning, we were always thinking about how to make the entire city a catchment in itself. So that includes HDB housing, it includes different terrains, and how water flows on them — how can all these contribute to retaining and conserving water.

But what’s promising is that young architects or architect groups in Singapore are using the “ABC Waters” Guidelines in very interesting ways. For example, WOHA Architects is using this in all their new projects. I think these kinds of things should be getting more and more normal, and that’s where Singapore can be a role model.

Q: You were involved in the Cambridge Road Project, which sought the views of residents surrounding Cambridge Road in greening their environment. What do you think were the lessons learnt about the positive role that communities can play in co-creating with governments blue-green spaces that are beneficial for all? In your current and future projects, what are the possibilities of collaborating with communities that you would like to experiment with in your design process?

A: We did this together with the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC) in Singapore as a pilot project to experiment with ways of involving the public. It was right at the time when COVID-19 hit

around the world. Under these conditions, we had to find new ways of participation and ways of involving people through online means. It was, in many ways, a very, very interesting experience. It's also a very good model for what Singapore can do, especially as a city which, in contrast to many Western cities or societies, does not have a very developed process of participation and involvement in planning and design.

Singapore still has more of the tradition of the government giving a very clear direction. The population is happy with this, and takes on this direction. This is a top-down approach, which makes things easier in some ways, but in today's society, people want to have a voice, they want to be heard. They want to take ownership in decisions. In this there are two parts, people want to take responsibility, but they also have to learn how to take responsibility. It's not only that you tell them what to do, but also that they have to be wise enough to know how to participate and contribute.

In the Cambridge Road project, we had many discussions, group meetings, talking to all kinds of stakeholders. Those from HDB housing, those from the older population's homes, those from private housing. And actually, some of them had previous experience with flooding — this was an area that was hit very often by flooding and by big storms.

So, it was very exciting to have a discussion. What would a solution look like? And what could we do for Cambridge Road? We had some bigger ideas that had to be taken down, because there were already other programmes going on. For example, we wanted a bigger open space in the school area, to make the transition between blue and green more seamless. But it was not possible, because the land was already reserved land for public schools. So, we had to work within limitations, to introduce green into corridors, into roads.

What we learnt was that people have the ability to organise themselves, and then, the project gains a momentum of its own. They had their own organisations. They brought in their own plant materials. They organised volunteer groups who started to bring in roadside swales and plants. Even maintenance of these were done by neighbours. There are now artists coming in. They bring in street art to some of the blocks, with interesting paintings and sketches. So, it's not only about fixing a problem, or working on a water solution, but it's also about giving people voices. It’s about allowing these voices to be strong and being all right with not completely controlling the process as you let the people get involved and help chart the direction.

Regardless, things will go in the right direction if you set the right frame, such that, eventually, the project doesn't need you anymore. It doesn't need a CLC.

This is an ongoing process where people become more aware about the environment, and become more involved in connecting with their neighbours and the wider society, including those who are of different generations, or who are persons with disabilities.

The Cambridge Road project is a role model for other places as well.

But public involvement is not easy

to do. It sounds easy, but it has to be done very professionally. You need very good mediation and facilitation skills. Very often, people come in at the start with their very fixed mindsets and opinions. These

could be from their tradition, from their politics, from their

pre-existing knowledge.

I have done lots of involvement projects in at least more than 100 projects around the world. What I have learnt is that it's very important to bring people in to take the individuals and not allow them to form groups with other individuals of the same fixed opinions. So, try to mix the people between the groups so that you don't have this group against that group.

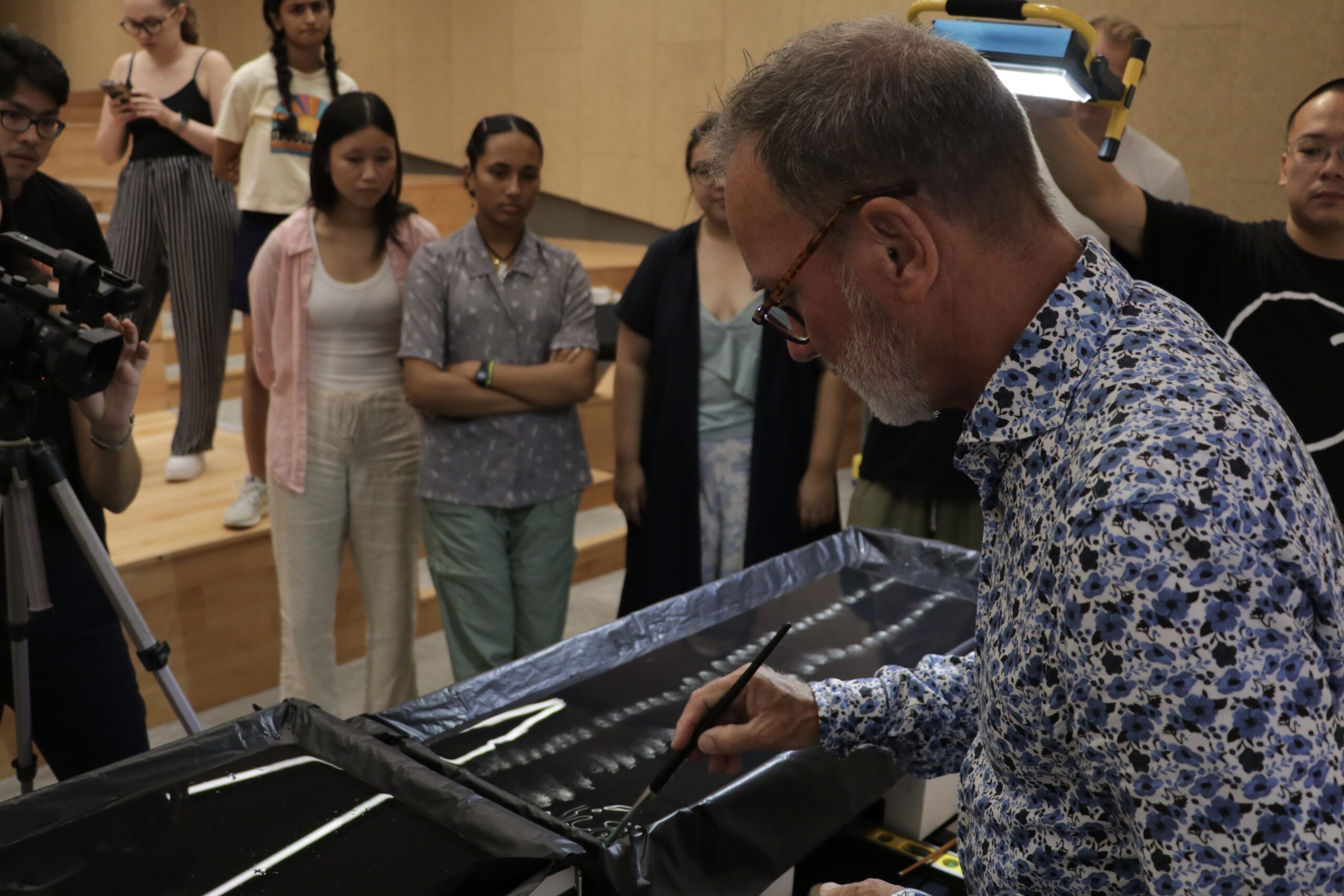

And then, what I often do in my process, is I start to bring the awareness of people to a very special focus on something where they learn something new. For example, I will do experiments where they can look at how water behaves in different conditions.

I will use this to facilitate the discussions towards questions such as, what would be a healthy structure and flow of water in nature and in our cities? What do we find in our cities today regarding this? How can we make the situation better?

Then, we get people to come up with ideas and visions, not of fixing a problem very quickly, but looking ahead 10, 20, 30 years from now, to a dream that they might have. And then, it becomes very interesting, because then you suddenly have the experience that even when individuals or groups with very conflicting political views come together, they often have the very same vision for the future. They just have different languages, or different ways or approaches of achieving that vision.

Following this setting of a common ground, we get the groups to become competitive, in that we give them the tools, we encourage them to be courageous in coming up with creative ideas. Then we assess who has the best ideas. We prompt them with questions such as, let's say in 20 years, you visit your neighbourhood with your grandchild. What would you like to see?

Working with different generations is very important. Usually in participatory processes, the older generations tend to talk more. They're used to expressing their opinions more. Young people are usually very shy. They are not so secure about their opinions. And when both groups interact, it can stifle the young people's ideas. Usually, the young people will come up with sometimes seemingly crazy, but sometimes really interesting, ideas, but those from the older generation start to question the feasibility of those ideas. That's a sure way to hold them back. They can't even start to fly with their ideas.

So, you have to provide the young people with a different environment to share ideas and discuss. What I often do is to bring groups of young people into a separate space where I say, this is your time to think and express freely. It's about your future. It's not about the future of the older generations ultimately. It's about your future.

Finally, what I think we did right with Cambridge Road is that we were very careful with expectations. In a participatory process, you have to be very clear what we are talking about. You have to be clear about the scope of discussion. This is so that people do not misuse the process to talk about irrelevant political discussions. The other thing is to be clear to participants that, ultimately, the final decision has to be taken and decided upon by the responsible stakeholders in the government.

I would love to see participatory processes like the project at Cambridge Road more, in Singapore and other Asian cities. People are often afraid of such processes, because they think that they will be seen as starting a revolution or disrupting society by doing so. But it needn't be thought of this way. Participatory processes, if done right, can garner support for the government, which is then seen as being responsive to realities and needs on the ground.

Q: Do you sense that there are differing levels of public participation between different countries?

Yes, there is a difference, due to different cultures and upbringing. But it's not an issue of saying, this one is better, or that one is better. They are just different, and they have their own strengths. In my experience, I have worked in participation processes around the world, and I would say, the Americans make it very quick. They are very outspoken, they immediately have an opinion, and you don't have to wait to get voices coming up. But you do have to manage the conversation because they can also be very, very wedded to their opinions. To facilitate these kinds of discussions is sometimes really an art. But it's very fun. I love to work in America, in participation projects, and I have had very, very successful ones there with hundreds of people.

Coming to Asia and Singapore, I think this is where it's a relatively new topic about how to do involvement and participation. It has to be done differently, because the culture is different. People are not like in America. People are more shy to express their opinions, they listen more. No one wants to lean out of the window because no one wants to lose face, so everyone wants to hold back. They think about what the others are saying before giving their opinion.

This is actually something that is a good practice. I like this very much actually because it's often very respectful and sensitive, which I often miss in other parts of the world. But I think what we need to do more in Asia is to create a kind of atmosphere of confidence and trust, and to listen to the younger generations, and the people on the edges of society. When it's done well, keeping the strength of the culture here, as well as improving it, you can have really exciting ideas and proposals coming up. I remember how with the Jurong Island Lake project, we were able to have a stimulating workshop for different stakeholders and groups, and that resulted in a wonderful project.

Q: What do you think are the most commonly overlooked reasons why blue-green infrastructure is important for the future of our cities and our societies around the world?

The most common reason why blue-and-green is often forgotten in decision-making by cities and governments is that space in cities is getting more and more scarce and dense. Traffic is taking a lot of space in cities. More and more space and density is needed because more and more people are moving to cities.

So, there is a fight, there's a conflict about space. And how this fight usually ends is that real estate development is winning because the stakeholders want to make money and want to be successful financially. It's not the park. It's not the green area. It's not the waterways. It's more housing, it's more industry, it's more shopping malls. It’s these kinds of developments where they can make a return on their money. That’s the way our values system is organised.

The people who work on green and on water tend to be the more idealistic dreamers, I would say. If their voices come up in some countries they tend to be the young people and the protesters. But so often, established society is ignoring them. The power of the voices of real estate development, as compared to those advocating for open space and blue-and-green infrastructure, comes through in different voices and different values.

And in this fight about space, often, even if we think it would be necessary to have more blue-and-green infrastructure, instead, roads, or big houses, or more density of industry is the winner. That's the reality. I mean, that's really what is happening.

To make a change, it needs a complete shift of mindset to recognise that we really have a problem with extreme flooding, and to recognise that we have to give more space to blue and green, to deal with the problem of extreme flooding. We have to give more priority to this, because otherwise we will kill ourselves and we will ruin the future. We are far away from what has been agreed upon between the governments of the United Nations at the various COP (Conference of the Parties) climate change conferences. And that's because of the reasons I just mentioned.

How can we make the change and how do we give more priority to blue-and-green infrastructure? I think that's something where Singapore can actually be a role model, where Singapore can give some hope to other cities. I think the discussion is such that if we only see blue-and-green infrastructure and “Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters” Guidelines as something to fix a problem only about water, then we are lost. But it’s quite different if we see it as a chance to also make our cities better, to make them more liveable, to make them healthier.

Focusing on health, we know that, in cities, active mobility is needed by the older population, but is still not widespread enough. We know that depression and dementia are connected to how people are not getting out of their homes enough, and that they don't see green as well. We know that psychological well-being is very much focused on the environment which is in the city.

The daily experience of listening to a bird singing, looking at beautiful flowers, seeing some green areas when we look out of the window or when we walk to the next MRT station — all these things happen in our unconscious, but they're so important for our wellbeing and for our mental health. When we create a better environment in our cities, we help to make our cities healthier. Having better water solutions also makes our cities healthier for people.

This is something which is more than just repairing something. It is actually an additional side-effect, an additional value-add to something we are missing and something we need very, very urgently. Also, the value discussion is starting to change, and people are realising that investing in blue-and-green infrastructure actually brings value back to the real estate developers. Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park is a good example, because for all these buildings around the park, their value was going up and became amazingly high, you know, because they all love to have a lookout over Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, and especially to the Kallang River.

It’s so cool to see grandparents taking their kids, showing them dragonflies and little frogs at the park – making it like a zoo! These qualities mean that real estate value goes up. And that's an interesting side-effect. I wish we would do much more research on that, how to change people’s mindsets, to overcome ignorance of the reasons why blue-and-green infrastructure is so important. I think we should also do some research, maybe at NUS, in this field, you know, because these are the big questions in society we have today, in many, many cities. I think Singapore has the best tools to take this discussion forward. I'm very often the keynote speaker in many international conferences, and people ask me: What is Singapore doing? Tell us more. Singapore has really a very, very strong position, I think, in that. Other cities and countries look up to Singapore to lead in this area. Singapore can give hope, give important perspectives, and, as a result, the symbolic capital of the country is increasing.

Q: You mentioned how the real estate prices were going up after Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park was completed, and in general there has been this critique of the way that some cities are introducing green into their cities, where, because of the way that it does improve real estate values, that greening cities becomes the cause of certain neighbourhoods becoming more exclusive to those who are able to afford those real estate values, rather than becoming a public space where people from all walks of life can enjoy the benefits of green that you mentioned. Have you encountered this issue in your own work? And how do you think cities can be more conscious of this issue, and deal with it such that greenery becomes a right for all?

I previously worked for rich private clients. I made private gardens for the Porsche family, for example, and others. I'm not working anymore with such clients, because of the reason you mentioned.

I really think that blue green infrastructure should be in the public realm, it should not be privatised. Singapore is a very good example where this infrastructure is being made accessible for as many people as possible, where neighbourhood parks and green corridors are open to the public and are near to public housing.

For me, water is a common good. Rainwater harvest or rainwater catchment systems and treatment trains can be private, but there should be more of these that have some form of public access. They should be for all people, something beautiful, something for the society.

I think this phenomenon of exclusive private terrain in gated communities might be seen by the people who live there as necessary to give them some feeling of security, but, in the long run, I think it is counterproductive to security. We should see more of the sharing of things, because it's also more safe.

If groups isolate themselves too much, we get a more dangerous situation in society, because then we have the people who are the rich guys who can afford this, and then we have a big base of people who have the leftovers to deal with, and there's usually less green.

There will be unfairness, and great aggressiveness. This creates crime, it creates vandalism. It creates all kinds of conflicts. And I think we should avoid that if we are wise.

And I think that's when I think about the politics also in Singapore. That's what the Government actually tries to do to balance this good hope that's answered.

Q: How important is aesthetics and design to the building of blue-and-green infrastructure and the functioning of cities in general?

A: Aesthetics and design really matter. Look at natural water systems around the world which are untouched by humans. Think about the landscapes, the mountains, the meadows, the tropics, the rainforests, and so on. Think about structures like the Rocky Mountains in America, the Himalayas in Asia, and the Alps in Europe, and the water bodies that lie in and around them. You will find that in these places, their beauty is always connected to their functions — how these landscapes play a role in benefiting the whole ecosystem.

Sudden weather situations that can carve out a whole part of a river, and then this river can bring flora and fauna into the environment. While these are examples from the natural world, design also matters in the city, especially where nature in the city is concerned. First of all, if we decide that something is beautiful and good, we take more care of it because we give it more value. We are more careful. We treat it better.

In my own city, which is a beautiful city, streets and roads are lively. Private investors are so much more willing, and so much more active, to keep their houses well-maintained. People ensure to avoid littering on roads. If there is rubbish on the roads, people pick it up and bring it to the nearby bin and clean it up themselves. They don't need the government to send cleaners or garbage trucks. It's actually maintained basically by common sense, because they say the beauty demands those living in the city to keep it nice.

If a city is awful, no one cares. Let's say there’s a cigarette, and you throw it down, and you'll leave it there because it's ugly anyway. And it's actually not only about keeping things clean. It's also about what I think is a very deep point on the psychological, or almost spiritual, side. When we are born on this planet, and when we live somewhere, a very important part is, how do we connect to the environment? How do we connect our inner feelings to the surroundings we have around us?

I was working with young people who were addicted to drugs. And one of the reasons was, of course, social reasons, for instance, a lot of problems with families, problems with work, and so

on. But a very big part of the reason was also that they felt that their environment was not inviting to them. They were not feeling that ‘the world loves me’. Instead, they felt that they were strangers and human beings who don’t belong there. The surroundings were not actually designed in a way that corresponded to their inner feelings. And I think this is very,

very important.

Does the world which we have created actually correspond with my inner being? Or is it so technical and ugly that I have to create my inner world separate from that which is out there? If it is so, then you get all kinds of, you know, crazy things such that people are taking all kinds of different drugs. But it's not only drugs, but it's also being in front of the TV all the time. Kids don't go out anymore. People create in themselves in an inner world, and they separate themselves completely from the outer world.

So, design also matters in the way that the surroundings should give you the feeling that this city loves you. And that you are part of this. So, I think design really matters very, very much in this field. It is also the way we invite plants, animals and the living environment into our cities, rather than keeping them out and making our cities ugly.

Q: You led the NUS Cities course Topics in Challenges of Cities: Nature-based Urban Innovations last year. What are the rewards and challenges of sharing your knowledge and expertise to undergraduates?

A: First of all, I love it. It's very nice to work with fresh undergrads on this topic because they have such good questions. How do you engage them? I think that the challenge is first to bring students to a point where they are not just at the university to get knowledge from some expert. I'm interested in creating courses about the challenges that cities face, nature-based solutions and urban innovations in a way that allows students to rediscover insights that they already know, but which they are not conscious or reflective of yet.

So that's why I ask students, for example, please describe how it was like when you were growing up? What was the landscape, water and the sea around you like? How did you experience these parts of nature?

And then, everyone starts to realise that it's not that I get knowledge from outside, but I get the instruments to learn how to engage with what I already know and how to develop that knowledge further, to let it flow, to let it flower and to bring it out. That's what I'm very interested in.

For example, during the Topics course, I organised a discussion for the students. In it, students take the position of different stakeholders and discuss arguments on how to make cities better. What arguments as a stakeholder would you need to convince another stakeholder of your position?

This is so important especially for undergrads, that they learn to see the challenges in cities as being extremely complex, which raises a lot of questions and arguments that you have to think through and discover and eventually, as fairly as possible, to balance between the different positions.

They have to learnt to ask: Why do people have something against a good idea? What is necessary to satisfy their needs to convince them to join you in making the world a better place? That’s what young undergrads actually need to learn. And I think the programme we have here at NUS Cities is fantastic because we bring so many different disciplines together. I think that's the future.

Q: Through all of your experiences, working with young people, being involved in the education of young people, do you sense more optimism or pessimism regarding the topics you teach, including on climate and environmental issues?

A: That’s a tricky question. Because on one hand, when I look around, I see how little change we as the human race are making in what is needed to tackle, for example, climate questions, climate change, sea-level rise, biodiversity or food systems in the world. I can be very depressed by that, you know.

But when I look at young people and the next generation and young people who are actually taking on these issues — I know so many of my colleagues, of my young colleagues, who were previously working in my offices all around the world — how many of them are actually taking leadership and running new companies, doing new projects that are actually creative, innovative and seeking to make a change in the world for the good.

Even when I look into the eyes of my grandchildren, I see much optimism. Because of these things, I have hope which keeps me going.