The Well-Tempered City, and its Landscapes of Opportunity

Sanjana Mugeraya sums up the key points from the ninth instalment of the NUS Cities Public Lecture Series on 23 January 2024. Jonathan F. P. Rose (founder of Jonathan Rose Companies and co-founder of the Garrison Institute) spoke about his personal experiences and insights, affordable and mixed income housing projects in the US, as well as ideas from his award-winning book “The Well-Tempered City: What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life”. The event included with a discussion moderated by Mr Anupam Yog, Managing Partner of XDG Labs.

Sanjana Mugeraya is a full-time Instructor at NUS Cities, has a Master’s in Integrated Sustainable Design from NUS, and has worked professionally as an architect.

Jonathan F.P. Rose is the Founder of Jonathan Rose Companies, and co-founder of the Garrison Institute.

Cities are a key part of human occupation of land, as well as centres for the future. However, given the rapid pace of globalisation and urban development, cities are now growing at a rate that outpaces the capacity that current plans, infrastructure and systems can accommodate. Cities are also consuming resources at an unprecedented rate, aggravating existing issues including climate change and pollution. Rising income inequality in many societies has led to social unrest and disruption in many parts of the world. In most cities, poverty and opportunity are unevenly distributed geographically, with poor neighborhoods often having poor access to good education, opportunities and healthcare.

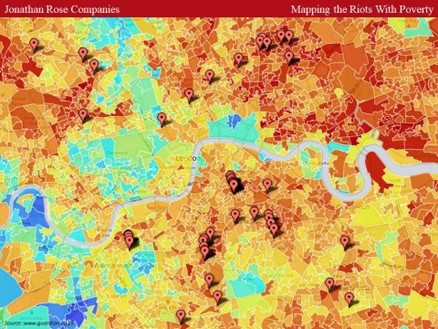

A map highlighting the locations in London where riots occurred in 2011 suggests that these riots did not take place in the poorest parts of the city, but actually in locations where the lower-middle class was meeting the middle class.

At such locations, the population sensed an invisible barrier of opportunity that they were unable to cross, leading to the creation of an atmosphere of social inequality. According to Mr Rose, the purpose of a city, amongst other things, is to equalise the “landscape of opportunity”, where every resident feels they have a chance to advance with respect to all aspects of their own lives and of their next generation’s.

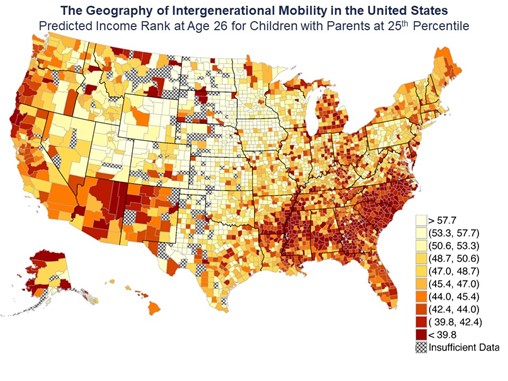

In 1966 (a year of peak opportunities in the US), regardless of race, a 26-year-old born into the bottom quintile of income in 1940, was 90% more likely to have a higher income than their low-income parents. Compared to this, for a 26-year-old in 2016, having been born into the bottom quintile of income in 1990, there is a two-thirds chance that they will be earning less than their low-income parents, thus suggesting that the US has gone backwards in terms of access to opportunity.

On deeper analysis and introspection, Mr Rose suggests that those places where the opportunities to move ahead intergenerationally are the lowest, are those neighborhoods with the poorest healthcare, poorest early childhood education, least affordable housing, and worst lack of transport systems. However, the residents mistake the reasons for lack of opportunity as immigration and other politicised issues, further polarising societies. Cities and nations that have equalised the access to opportunity have been able to move forward from the issues of resentment and grudges, and to deal with other real issues that societies face.

Lessons from Cities of the Past for Cities of the Future

Cities are places where people meet and interact, and so, have the potential to host the deeply needed solution to all the issues that humanity faces in these volatile times. History shows how even hunter-gatherers had the capability to build enormous palaces and temples with stone, with less technological/mechanical access, but just brilliant social organisation revolving around centres of worship.

Mr Rose strongly feels that if cities can regain the sense of a spiritual connection to a place, and also make a resident feel grounded to the place, along with a connection to the larger universe, this would be a pathway to greater well-being in cities.

In the model of the first city Uruk, in ancient Mesopotamia, there is a key philosophy centered around a God of Chaos and a God of Order, with a healthy city needing to strike a balance between both. There needs to be enough freedom and openness of opportunity, along with a sense of order and control in place. Mr Rose added that, in today’s world, cities are becoming either over-chaotic with no control, or overly rigid. Rigidity in cities can reduce their capacity for creativity, as seen in recent developments in Hong Kong, thus becoming less of a city that could contribute to the transformation of the world.

This balance between openness of ideas, expressions and opportunities as compared to the order and control in cities, needs to be delicately managed, as seen in Singapore’s approach towards this balance.

There was also a moral and ethical purpose to leadership in ancient cities, which can be seen in the code of Hammurabi, king of Babylon in 1754 BC, where he describes himself as a shepherd of his city, who was ruling to further the well-being of mankind. The ideas of justice, equality and protection are rooted in the legal, social and moral codes of these cities. These are the crucial elements to take forward into the future.

"...First came the temple and then came the city..."

- Jonathan Rose

What do Cities need, and how should we plan or build for it?

Mr Rose detailed his current work as an advisor for the masterplan for the capital city of Thimphu, Bhutan. Between 2003 and 2023, urban planning in Thimphu had unleashed private development, but had failed to plan for public development. Cities are a balance between private and public good. The public good does not include only service infrastructure, but also conceptual and physical communal facilities that bring communities closer and tie them back to the place. The new masterplan now seeks to bring the public and the private good back into balance. One of the masterplan’s primary goals is to aim for Green and Resilient Urbanisation, to ensure and optimise the people’s contact with nature. The goals would include aspects such as conservation of natural capital, green energy transition, carbon stewardship, water and food security, and there is a need to do all this through community engagement.

It all starts with planning, especially community-based planning. It is very crucial to also make the plans very coherent and clear to the community. For example, Portland, Oregon, in the US used collages/images to help connect to the community, to explain ideals and values to the people. It is not just vital to have a plan, but the people of the city should be able to understand and embody it as a vision for their future. London’s vision for the future has slow aspirations of a greater density with greater greens, interconnected with a better transport system, and doing this in a way that is environmentally responsible.

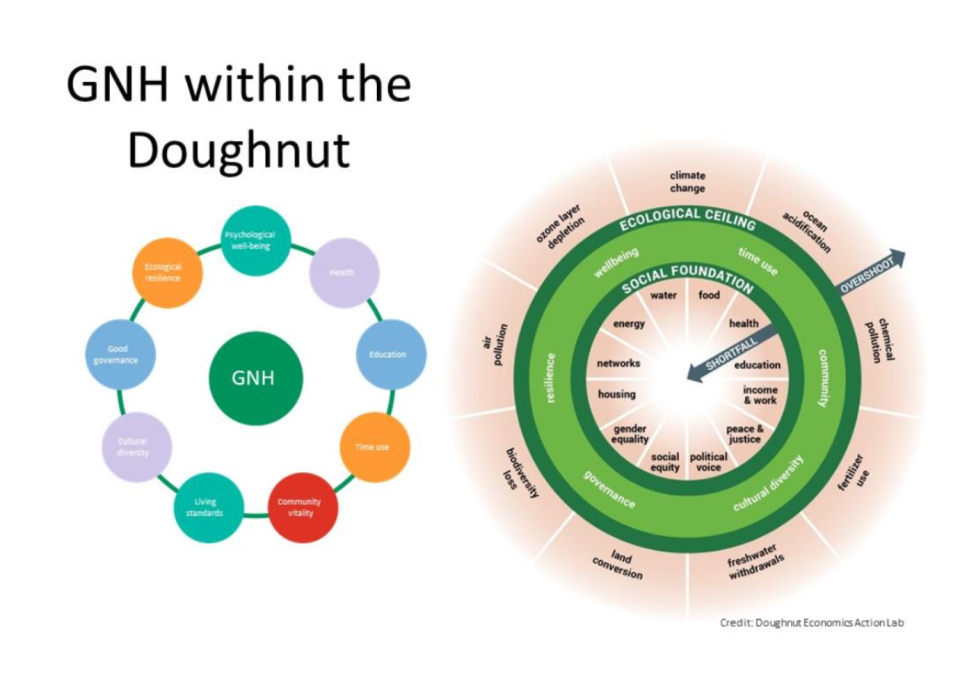

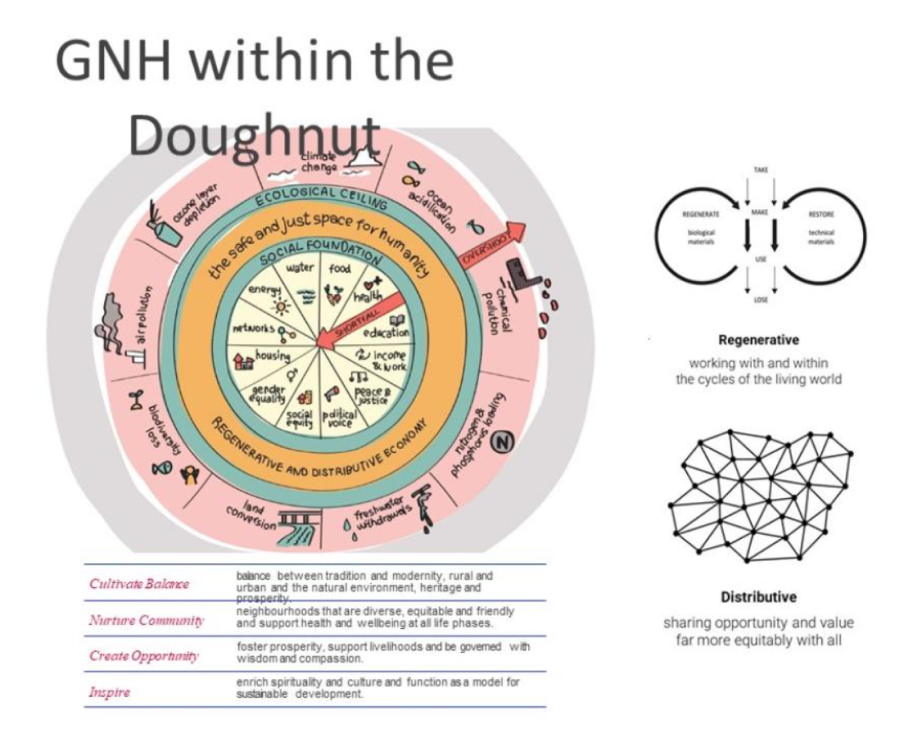

Mr Rose emphasised that it is critical to measure progress, as he spoke in detail about the Gross National Happiness (GNH) system, as well as the Doughnut Economics model. He highlighted the need to design an economy that provides sufficient social support but limits ecological impact. Hence, combining the GNH model with the Doughnut model, one can conclude that there is a need for an economy that is both regenerative and distributive.

"...What do cities need? I have put the design and management of cities into five buckets: Coherence, Circularity, Resilience, Community and Compassion..."

- Jonathan Rose

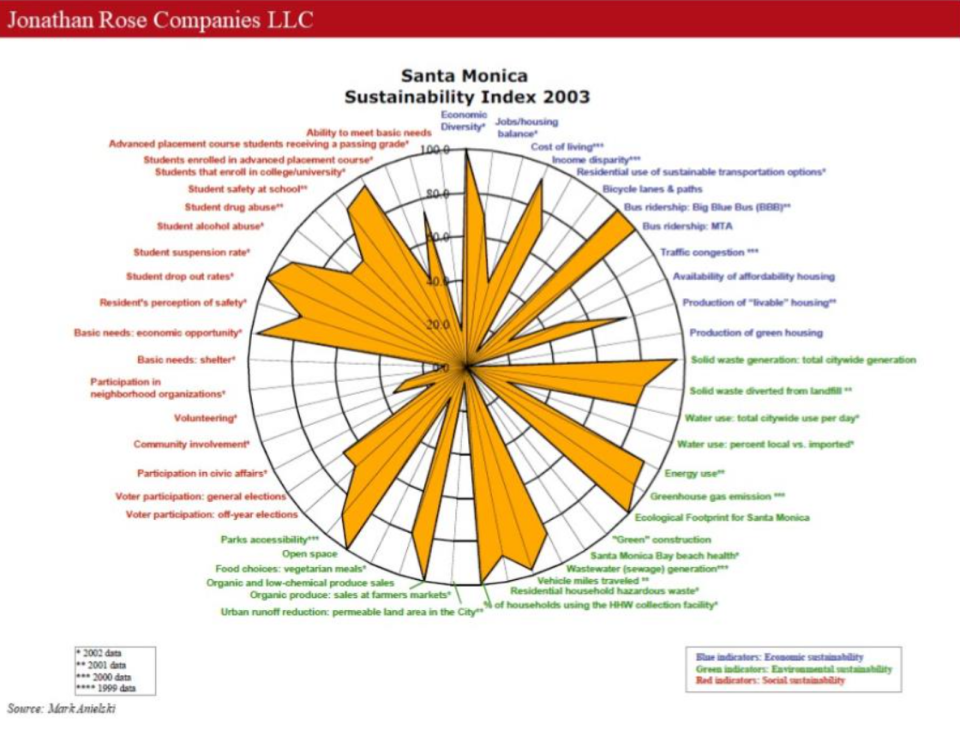

Mr Rose further elaborated on the importance of such planning and measurement frameworks, by explaining the Santa Monica Sustainability Index, that emerged in the early 2000s. This index is composed of “community health indicators”, which can be subjective to the needs of the context and location, with no restriction on the number of indicators possible. It can include factors such as the amount of open spaces, the quality of the bike lanes in the city, and even the amount of greenhouse gases emitted, participation in civic affairs and school dropout rates.

These indicators can be measured, in relatively real time, and can be used as a reporting mechanism for citizens, as well as a mapping framework to see how well a city is doing. With cities taking a long time to plan and then to execute the plans, there is a need to constantly adjust the plans on a real-time basis, based on the changing needs of the city. With real-time feedback, there should be reallocations done annually, to optimise amongst all these different goals, as well as adjustments on how the city is being run.

New Ways of Building

Mr Rose echoed the need for new ways of building through different examples of programming, technology, incentivisation and capacity-building.

Would it be possible to convert 40,000 dull and dangerous construction jobs of imported labour, and turn them into 10,000 much healthier dignified high-tech jobs that actually create a circular system within the country itself? The vision of the new Thimphu Masterplan is to tap into Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) as a leverage point, to help create a technically more informed and competent local labour force within the country. This would thus create 10,000 local jobs, using locally imported

generated materials like CLT and rammed earth, to make higher-quality buildings through traditional methodologies, leading to a regenerative way of construction.

The cost to use higher-value local labour vs cheap migrant labour will always raise construction costs. This is an ethical question that cities need to decide on – are cities aspiring towards only physical outcomes, or to benefit all of society? In most developed societies, the younger generation generally does not want to enter the construction trade. However, with the creation of factory components and on-site work being only assembly, especially for materials like Mass Timber Construction, the construction trade then portrays itself as more technical work, much more highly-skilled, and a higher-respect job with higher pay, with maybe only three people on-site with a crane operator.

Another example that Mr Rose presented is the Via Verde project in South Bronx, New York, in the US. As a beautiful model of affordable housing, this building used prefab construction, solar roofs and passive shading strategies in its design, as well as interior courts, terraces and community gardens creating communal areas for community gathering. Not only limiting itself to the provision of built infrastructure, the project also critiques health infrastructure in affordable housing, by providing exercise rooms in daylight areas, to encourage more usage, as well circularity through organic waste and water recycling.

When questioned about the role of developers in creating well-being in cities, Mr Rose emphasised that developers are creators, and there is an enormous creative potential that needs to be unleashed as well

as incentivised.

An example of this can be seen in the effects of the Green Standards for Affordable Housing, created in the early 2000s by Enterprise Community Partners, for the affordable housing market in the US. Form follows finance, and using this ideology, the Enterprise Community Partners developed a Green Guideline and collaborated with state agencies that allocate money for affordable housing, to award subsidies for incorporating green design principles into the design.

One needs to compete for green points, with the most green points winning subsidies. This helps reset the playing field from telling developers to build a greater number of units for the least number of dollars per unit, to giving points for design excellence and greenness.

Changing the incentive system helped in creating a great response from developers, leading to very creative and green building topologies for affordable housing. If more of the right signals and conditions are created, the private sector will be more motivated to then create more amazing and innovative typologies.

Compassion and City-Making

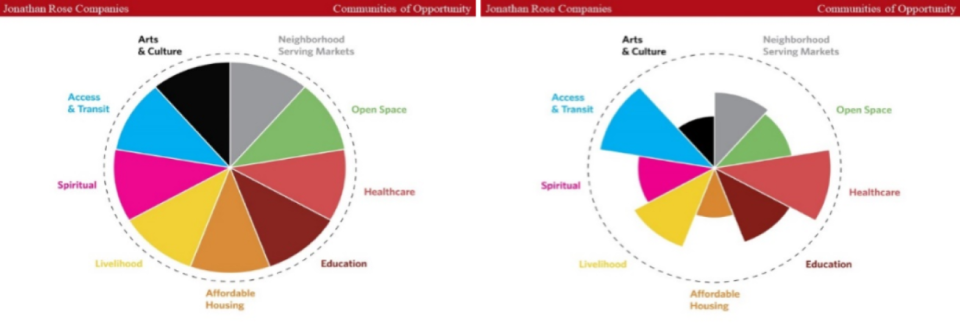

Mr Rose then addressed social connectivity and resilience – the idea of building compassionate communities that could be designed to solve the issue of distribution of opportunities.

The connection between city-making and compassion can take place at various levels. Cities need to ponder this: What is the purpose of the city and its leadership? Ideally, they need to equalise the landscape of opportunity. When the social foundations are taken care of, according to Mr Rose, they are the best expressions of compassion. If people feel safe in a city, they then start to expand their boundaries of who they think their tribe is, or how big their tribe is.

In Bhutan, in the rural areas, people live in beautiful big houses, built of local timber, and by local labour. The process of construction is very communal in nature. The family might hire a master carpenter, but the community volunteers for the construction of the house. Wood is not bought, but cut from a communal forest. The main idea is to build beautiful houses for the family without debt, and by owning them without debt, they live very comfortable lives without the burden of paying loans. The whole model is based on a mutual system that helps the community de-finance relationships, and so, increase trust and mutuality.

When posed the question about finding a balance between intellectualisation and intuition in planning of cities, Mr Rose emphasised that there needs to be more intellectualisation, since many cities have become more ignorant and bureaucratic.

There is a need for city intelligence — not a fancy software-based model, but a more community needs-based intelligent approach. There is a huge need to gather people’s needs, and translate them into process and outcomes. The physicality of the city and the information systems need to be more dynamic to let the city evolve to meet the true basic human needs, as well as higher needs.

One of Mr Rose’s projects, Via Verde was won through a design competition, where the competitors were not allowed to speak to the community, but got to hear the community through meetings in South Bronx. One of the residents said he would love a jacuzzi in his new apartment.

A normal response would to mock such an ambition, but what Mr Rose interpreted from that particular desire is a need to be treated with respect and a sense of pride in the new apartment, which was being conveyed using the jacuzzi as a tool of health. The idea was then translated into amenities for the building, which show respect for the residents and their health, which led them to win the competition.

Such an interpretation is a good example of intellectualisation vs intuition — here, there is a kind of listening that requires intelligence, to try and understand the essence of human needs and aspirations. There is also a need to understand the essence of non-human species, such as the surrounding wildlife and domestic pets, because cities can really only thrive in a deeply biologically rich world.

One of the ways Mr Rose’s company, Jonathan Rose Companies, builds social connectivity and resilience is by using investment funds to buy existing affordable housing, retrofitting them to make them green, and also bringing in social, health and education programmes to the residents.

Community spaces and programmes including community gardens, green spaces, community rooms, computer rooms, a library, fitness rooms, cultural activities, after-school programmes for kids, and medical labs/health examination rooms, are also inserted into the projects, turning existing affordable housing into landscapes of opportunities.