Upping the Game

Up till now, simulations like city-building games have helped urban studies students and city planners grasp the complexities of running a city. To what extent can this field up its game, with workshops like those developed by the Urban Land Institute, that add trained facilitators and expert industry evaluation, so as to calculate real-life tradeoffs, and also factor-in soft factors like emotional appeal?

TK Bean,

is a full-time teaching assistant at NUS Cities, with a background in urban studies.

Educators and planners have long recognised that simulations, like the city-building games (CBGs) SimCity and Cities: Skylines, can help students and citizens understand the complexity of running a city. CBGs enable players to gradually understand the multiple consequences of each of their actions on the city through quickly simulating their impacts. The players can then respond, and through further trial and error, figure out what types of actions could benefit their cities most [1].

Game developers choose to sacrifice some realism to ensure CBGs remain fun. This means that CBGs have limits as educational tools. For example, while CBG players do have approval ratings and feedback, they do not have to worry about getting voted out of office so long as they maintain a budget surplus. Concerns such as heritage preservation and providing affordable housing do not matter if they do not appear to impact the budget in the short-term. CBGs also tend to simulate car-centric American cities, and do not reflect as well cities in other contexts, like Europe and Asia [2].

Some educators address these limits by getting students to work in teams, or represent different interest groups in the classroom. Others have found that when students return to these simulators after a semester in their geography and/or planning classes, the process of critiquing their limitations becomes a way to learn too [3]. CBGs, while popular, are not the only type of educational game available in planning, though. In-person workshops, when well-designed, can offer opportunities that CBGs cannot.

CITY-BUILDING GAMES (CBGs)

Players generally take on the role of an all-powerful mayor who develops an empty piece of land into a growing metropolis. They expand their city through zoning land for residential, commercial, and industrial uses. Players must continuously balance between their revenue and spending to ensure that city dwellers have access to services like education, healthcare, fire stations, and public transport. As their city grows, they also need to address issues like pollution, garbage, and traffic congestion time.

SimCity and its sequels are the most well-known game within the genre. They have introduced many planners in the United States to urban planning. Cities:Skylines has become the current leader in the genre.

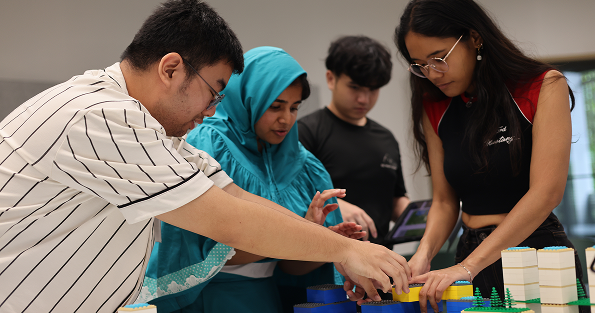

At a recent UrbanPlan workshop developed by the Urban Land Institute (ULI), each of the five participating teams at NUS Cities had a map representing a district on the fringe of the Central Business District of a fictional city, and a large tray of Lego bricks covered with a piece of cloth laid out on their table. As soon as the time to work on their proposals began, some teams immediately pulled off the cloth and started rearranging the colourful chunks of Lego into different configurations. Others carefully surveyed the map, gesturing to various features of it as they discussed their options.

The UrbanPlan workshop simulates how real estate development companies prepare proposals to regenerate an urban precinct. Students learn how to work collaboratively in teams, and think creatively and critically through experiential learning. They have to present their proposals to convince decision-makers of their vision for creating vibrant, inclusive neighbourhoods that are socially desirable and economically sustainable.

The UrbanPlan workshop simulates how real estate development companies prepare proposals to regenerate an urban precinct. Students learn how to work collaboratively in teams, and think creatively and critically through experiential learning. They have to present their proposals to convince decision-makers of their vision for creating vibrant, inclusive neighbourhoods that are socially desirable and economically sustainable.

The teams must propose, and present to a panel of judges (City Council members), a holistic response to place-make four mostly vacant blocks near the city centre. Their development had to yield a minimum return on investment, whilst trying to meet the city’s preferred criteria, such as preserving existing heritage buildings on the lots, providing adequate affordable housing, and constructing a waste management facility for a neighbouring district. Meeting such criteria may adversely impact their prospective profits. Deviating from the criteria would lead the municipality to have to levy additional development charges on them.

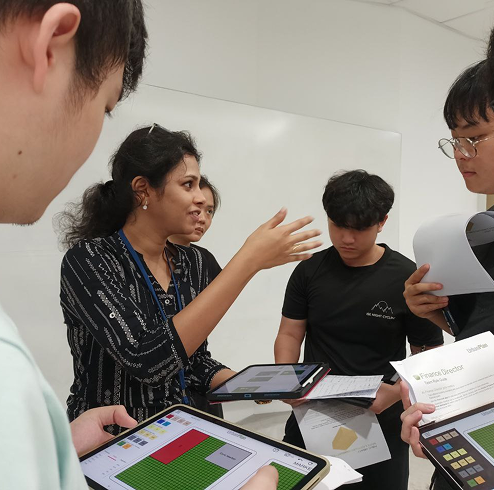

The ULI member-volunteer instructor assigned each member of the team a role that parallels jobs found in real estate development firms. One team member had to estimate the budget and expected revenue of the project, to ensure it generated a minimum return on their company’s investment. Another had to ensure the project met sustainability targets and produced enough renewable energy. Sometimes, the goals assigned to each team member conflicted with those of the municipality or their other team members. This forced the team to negotiate tradeoffs and work on a compromise that is acceptable to all stakeholders. Meanwhile, the trained multi-disciplinary volunteer facilitators guide students to think creatively and critically, using the Socratic method.

Participants in the UrbanPlan workshop found the need to work as a team, as well as the use of physical Lego blocks, very effective for helping them learn. Shu Qi shared that working with the Lego made it “much quicker and efficient” to iterate through different scenarios, allowing her team to “immediately see how changes can affect the overall plan”.

Sanjana, one of the workshop facilitators, added that having a physical model reduces communication barriers by allowing them to express and read each other’s ideas. She believes that learning through physical movement also helps to reinforce an intuitive understanding of the complex economic and social aspects of urban design in a way that visual and audio methods alone cannot.

The ULI also invited experts from professions in the built environment sector, including architecture, sustainability, and real estate, to evaluate the students' proposals and give feedback based on their real-world experience, to help the teams refine their proposals before judging them in the final presentation. Another participant, Yi De, felt that the facilitators gave “meaningful insights”. Fazil appreciated the questions posed by the facilitators as they pushed the team to refine and articulate their ideas better.

The need to pitch their ideas in-person also meant that participants must ensure that their projects do not just meet technical requirements, but also have emotional appeal. Fazil recalled one of the ULI members sharing that “a city isn’t just about being liveable...it should also be lovable”. He learnt it is the “emotions, memories, and heritage tied to spaces that make a city truly meaningful”. Many participants picked up on this lesson. During their presentations, they asked their audience to imagine themselves living in the redeveloped districts, and enjoying moments like having a meal with friends, or watching the sun set over the ocean.

Of course, in-person workshops have their limitations too. ULI had to greatly simplify the processes in real estate development, such as calculating carbon emissions and returns on investment, so that the learning curve remained manageable. Students could then focus more on weighing different tradeoffs, rather than executing tedious procedures in the limited time given. The need for trained ULI volunteer instructors and facilitators from the industry also makes it harder to scale up to hundreds of students in the same way CBGs can.

Games and simulations, both because of, and despite, their limitations, remain effective tools for engaging students in the classroom. Educators should explore and experiment with adding different types of simulations to their curriculum to best assist their students’ learning.

References

[1] Bereitschaft, B. (2016) “Gods of the City? Reflecting on City Building Games as an Early Introduction to Urban Systems”, Journal of Geography, 115:2, pp. 51-60, DOI: 10.1080/00221341.2015.1070366

[2] Lobo, D. G. (2004) A city is not a toy: How SimCity plays with urbanism. Discussion Paper 15/05, Cities Programme: Architecture and Engineering, London School of Economics and Political Science.

[3] Nilsson, E.M., Jakobsson, A. (2011) “Simulated Sustainable Societies: Students’ Reflections on Creating Future Cities in Computer Games”. Journal of Science Education and Technology 20, pp. 33–50. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1007/s10956-010-9232-9