Follow CDE

PDF Download

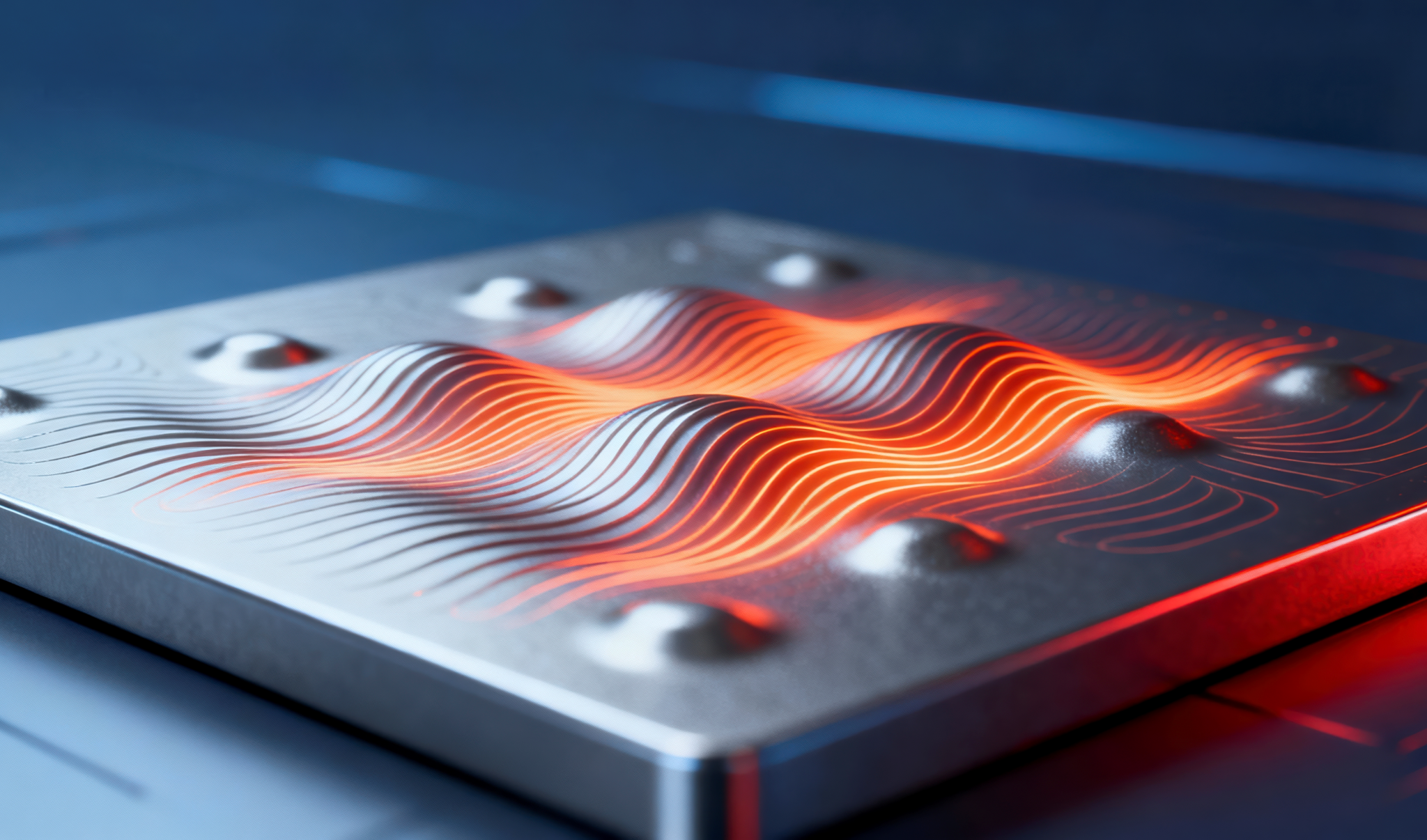

A new nanoscale design channels hybrid light–vibration waves to carry heat more efficiently, allowing better thermal management in compact, energy-hungry electronics.

Your phone warms up after a 20-minute Facetime call. Your laptop hums loudly while editing a large video file. Heat is a by-product of modern electronics — from everyday gadgets to the high-resolution screens and processors that power electric vehicles.

As components get smaller and more powerful, that heat becomes increasingly difficult to tame. In the cramped spaces of modern chips, the usual carriers of thermal energy — electrons and phonons (the tiny vibrations of atoms) — keep colliding

Assistant Professor Shin Sunmi and her team introduced a new nanoscale design that channels heat more efficiently, allowing better thermal management in compact, energy-hungry electronics.

with surfaces and scattering in all directions. Instead of dissipating, that heat lingers instead, straining energy efficiency and making devices fickler.

Assistant Professor Shin Sunmi pondered if heat could be made to move differently, not through the chaotic jostling of particles, but in waves. At the Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, her team turned to an unusual phenomenon called surface phonon polaritons (SPhPs): ripples that arise when infrared light couples with atomic vibrations on the surface of certain materials such as silicon dioxide. These hybrid waves behave like guided beams of thermal energy, theoretically able to travel long distances without the usual loss from boundary collisions. However, in practice, they’ve remained elusive — hard to generate, harder still to detect.

“The idea of using light-coupled waves to carry heat has been around for some time,” says Asst Prof Shin. “The challenge was how to actually measure them and confirm that this invisible form of heat flow truly exists in solids.”

Catching invisible waves

To make those waves visible to measurement, Asst Prof Shin’s group designed a grating-enhanced micro-thermometer — a suspended device with two thin beams connected by a nanoscale bridge of silicon dioxide. One beam serves as a heater, while the other acts as a sensor. The sensing beam’s surface is patterned with a fine grating, just a few micrometres wide, that lets the mid-infrared waves couple into it more effectively.

The pattern allows the surface heat waves to be absorbed instead of bouncing off, much like how the V-shaped grooves on a vinyl record captures sound waves. Computer simulations showed that this design nearly doubles the amount of infrared energy absorbed across key wavelengths, greatly improving the detectability of SPhP-mediated heat flow.

When the team tested heat channels of various lengths, they noticed something unusual. In shorter channels — just tens of micrometres long — heat seemed to flow effortlessly, barely slowing down with distance. Instead of scattering in all directions, it travelled almost as though riding a guided wave of light. The team’s measurements also confirmed it. Even in structures a thousand times thinner than a human hair, heat moved nearly as efficiently as it does through bulk silicon dioxide. Devices with the patterned grating design showed a marked improvement too, carrying about 70% more of this light-driven heat than their flat-surfaced counterparts.

“It was surprising to see heat behaving almost independently of distance.”

“It was surprising to see heat behaving almost independently of distance.”

“It was surprising to see heat behaving almost independently of distance,” Asst Prof Shin notes. “That’s a clear signature that these surface waves can act as long-range energy carriers, even in structures this small.”

The team’s design, detailed in their new paper published in ACS Nano, not only confirms that SPhPs can move heat efficiently, but also provides a way to tune how well they interact with solid structures — by adjusting the geometry rather than changing materials.

“It was surprising to see heat behaving almost independently of distance.”

New ways to control heat

As data centres mushroom across the globe, driven by the boom in artificial intelligence, the world’s ever-growing appetite for computing power is also fuelling an “electronic heat wave.” A large share of the world’s energy bill today goes simply into preventing machines from overheating. Finding new ways to direct heat could make future electronics leaner, cooler and far more energy efficient.

The researchers’ solution is elegantly simple: instead of relying on bulky heat sinks or exotic materials, it reshapes surfaces at the nanoscale to influence how heat moves across. Shaping how light and matter interact at the nanoscale enabled the team to open a new route for managing thermal energy where traditional methods lack gusto.

In principle, devices that can guide heat in this way could help reduce dependence on fans and heavy thermal components, improve the stability and performance of compact chip designs and make electronics more resilient in high-temperature or demanding environments — from electric drivetrains to wearable sensors and photonic circuits. On a larger scale, with cooling already accounting for up to 40% of total power use in some data centres, even modest improvements in how heat moves through chips may translate into meaningful energy savings.

Looking ahead, the team plans to probe the theoretical upper limit of how much heat surface phonon polaritons can carry, and to demonstrate thermal routing, using these guided waves to steer heat intentionally across micron-scale paths. By integrating such wave-based heat channels into next-generation, chiplet-based microelectronics, the team aims to show that nanoscale surface design can serve as a practical cooling strategy for densely packed, high-power chips where conventional heat-spreading methods reach their limits.

Read More

View Our Publications ▏Back to Forging New Frontiers - December 2025 Issue

If you are interested to connect with us, email us at cdenews@nus.edu.sg